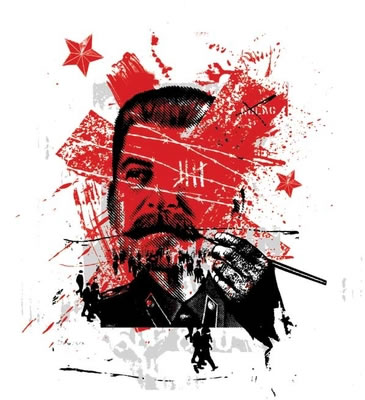

In Georgia, of course, he never really disappeared. Statues of the country’s most famous, or infamous, son were still standing when all others were removed across the Soviet Union on Khrushchev’s orders. But Stalin, for so long an unperson in the country where he made millions of others unpersons, is quietly making a comeback. As Russia prepares to celebrate the 65th anniversary this year of victory in the Second World War, his name is again mentioned with pride. His drastic industrialisation policies are held up for praise. And his repressions, purges and mass murder of millions of Russians are glossed over, airbrushed from the record just as his enemies were once airbrushed from photographs and official history.

For millions of Russians, the partial rehabilitation of Stalin is a source of pride. He was the man, they say, who made Russia great, who created its industrial strength, beat Hitler and raised the Soviet Union to superpower status. Russian nationalists, who have been feeding on the populist resentment at their country’s loss of empire, its dwindling economic power and diminished global influence, have seized on Stalin as the symbol of ruthless strength. Stalin, they suggest, would never have tolerated the crime, the indiscipline, the oligarchs and the inequalities that they so resent in modern Russia. Russia was great when its leader was all-powerful.

By definition, this nostalgia for a dead dictator comes from those who survived his purges. Millions did not. And millions of Russian families can point to a grandfather, a great-uncle or neighbours’ whole families who simply disappeared, taken from their homes at night and never seen again. But apart from Khrushchev’s “secret speech” denouncing him in 1956, there has never been a proper reckoning or public acknowledgment of the crimes that engulfed two generations of Russians. The communist leadership never fully repudiated the system that Stalin put in place and that they inherited. And Vladimir Putin, who declared that the collapse of the Soviet Union was the greatest tragedy of the twentieth century, has snuffed out even the tentative post-communist efforts to account for Stalin’s crimes.

Stalin’s return has been largely in the context of Russian history. The dictator used to order history to be rewritten all the time, falsifying events to conform to the party line. Now, once again, the books that Russian schoolchildren study are being changed. The new emphasis is “positive history” – a more upbeat version of the misery inflicted on Russia after 1917. That means an emphasis on patriotism, on Soviet as well as Russian achievements. And the order comes directly from Putin, the former President and still, as Prime Minister, the dominant political force in Russia. It was he who, in 2007, told a conference of Russian educationists that the country needed more patriotic history to reinstil national pride and social discipline. He sent out the message that textbooks should not include material that filled Russian children with horror and disgust about their past and their people. He pushed through a law that gave the state power to approve or ban history books in school.

The result is a distortion almost as grotesque as the lies that were taught in Stalin’s time. A book by Aleksandr Filippov, Putin’s Positive History exponent, describes Stalin as an “efficient manager”. Some 83 pages are devoted to his industrialisation; a mere single paragraph describes the man-made famine in Ukraine in the early 1930s, when millions starved as food was confiscated from peasants reluctant to join collective farms. Stalin’s wartime leadership is held up for praise. But there is not a word about the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact that carved up Poland and gave Hitler a free hand to invade. Filippov almost suggests that the Western allies did not fight Hitler, left the Russians to face the Nazis alone and tried to negotiate a separate peace with Germany at the end of the war.

The distortions may be historically infuriating. But they are more dangerous than that. They have fanned new suspicion of Russia’s intentions among its neighbours. Ukraine’s attempts to remember the Great Famine have been denounced as a hostile move by Russia. The Kremlin repeatedly tried to explain away or justify Stalin’s Pact with Hitler when the rest of the world marked the 70th anniversary of the start of the Second World War.

In other quiet ways, Stalin is reappearing. A famous frieze saluting Stalin in one of the Moscow metro stations was removed in 1956; a month ago, with no publicity, it suddenly reappeared, and passengers now pass through a hall bearing the inscription: “Stalin raised us to be loyal to the nation.”

Stalin is no longer a taboo figure for Russia’s leaders: in his annual marathon phone-in last December, Putin openly praised his achievements, noting Russia’s rapid industrialisation under his leadership and Russia’s victory in “the Great Patriotic War”, as Russia calls the Second World War. “Whatever anyone may say, victory was achieved. Even when we consider the losses, nobody can now throw stones at those who planned and led this victory, because if we’d lost the war, the consequences for our country would have been much more catastrophic.”

Putin’s praise was not unqualified: that would be straining even Russian credulity too much. The Prime Minister acknowledged that there was repression. “This is a fact. Million of our citizens suffered from this. And this way of running a state, to achieve a result, is not acceptable. It is impossible.”

What frightens intellectuals and liberals in Putin’s Russia, however, is that some of Stalin’s ways of running a state are returning. The Kremlin no longer tolerates media criticism. It has clamped down on independent parties, non-governmental organisations, any institution not under the supervision or control of the government. And one of the bodies that has suffered most from harassment has been Memorial, the organisation set up to document and publicise Stalinist repression. Last year the authorities raided its offices in St Petersburg, and seized records and data that logged the deportations. If these archives are again permanently closed, families hoping to trace what happened to their relatives will again find only silence.

Many Russians hanker for a return of the idealism, the patriotism and the social discipline now associated with the early years of communist rule. But not all Russians want a return to Stalinism, especially not the Russian Orthodox Church and the millions of believers fuelling a religious revival in Russia. President Medvedev, who tries to portray himself as more liberal and less the son of the Soviet system than Putin, forcefully condemned Stalin’s rule in October, the day that Russia commemorates victims of political repression. “Millions of people died as a result of terror and false accusation,” he said. “But we are still hearing that these enormous sacrifices could be justified by certain ultimate interests of the state.” He said it was important to prevent any attempts to vindicate, under the pretext of restoring historical justice, those who destroyed their own people.

In Soviet times, there were occasional surreptitious attempts to whitewash Stalin. In 1979 the official media marked the centenary of his birth. Black-market pictures and statuettes of the dictator used to be sold – mainly by Georgians – on long-distance trains. There was a thriving underground market, now open and very expensive, in Stalin memorabilia: busts, plaques, paintings and banners. And one of the most active guardians of the Stalin flame was his grandson, Yevgeny Djugashvili, a former army officer who bore a striking resemblance to the dictator and stood against Yeltsin after the collapse of communism as the main candidate for the Stalinist Party of the USSR. He received a hero’s welcome when he travelled around the country campaigning. But his party received almost no votes.

Nationalist nostalgia is one thing: a real return to Stalin’s ways is quite another, and to most Russians today would be anathema.

Letters to the editor: send us your thoughts for our letter pages by email to editor@newhumanist.org.uk