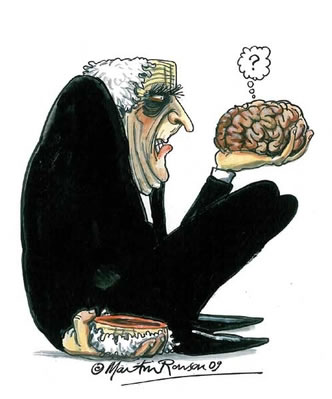

I heard a neuroscientist on the radio saying that all the wonderful new work being done in his discipline would help us all to get on better terms with our own brains. I really do hope so. For recently my own brain has been acting more and more in a manner that can only be described as perverse.

I heard a neuroscientist on the radio saying that all the wonderful new work being done in his discipline would help us all to get on better terms with our own brains. I really do hope so. For recently my own brain has been acting more and more in a manner that can only be described as perverse.

Take last week. I was lying in bed reading a little Lacan in preparation for the following day’s graduate seminar and came across this passage: “Female sexuality appears as the effort of a jouissance enveloped in its own contiguity in order to be realised in competition with the desire that castration liberates in the male in giving him the phallus as a signifier.”

Now even an apprentice Lacanian would agree that this was pretty straightforward stuff. There’s nothing at all complex about the sentence structure, no problems of definition with the actual words. (“Jouissance” is now such a familiar term for extreme sexual pleasure that I’ve even heard it used by revellers on late-night buses.) But nevertheless on this occasion my brain quite perversely decided that it would sit sulkily in the far corner of my skull and feign incomprehension.

“Come on,” I told it firmly. “Get a grip. What’s the matter with you? What’s giving you so much trouble? Start from beginning. Right. ‘Female sexuality appears as the effort of jouissance.’ Got that? Right. And that jouissance is enveloped in its own contiguity. No problem there, is there? And now the last bit. Why is the jouissance enveloped in its own contiguity? Well, it’s hardly rocket science, is it? It’s enveloped in its own contiguity ‘in order to be realised in competition with the desire that castration liberates in the male in giving him the phallus as signifier.’ That’s all there is to it. Now, please let me understand it. You’ve had far worse than this to master. You really have. Remember how good you were on Heidegger last year? And now you’ve given up on this. You have given up, haven’t you? You’re not even trying any more. You’re pretending not to know.”

It’s not as though I make my brain work particularly hard. In fact I’m quite a libertarian in this respect. If it wants to wander off on its own when it should be attending to other more proximate matters I’m inclined to let it go where it wants. During that recent film about the life of Keats, for example, it suddenly decided it was bored with attending to the poet romping around on Hampstead Heath with his mistress and went off on a little freewheeling stroll around the recent ill fortunes of Liverpool Football Club. It was a cheeky thing to do in the middle of a well-reviewed film by a leading feminist director but then I reasoned that it had stayed properly on the job during a long afternoon editorial meeting at New Humanist and so probably deserved a little free association.

When I mentioned the problem to my relationship counsellor she said it was not quite in her field but wondered whether I’d given any thought to cerebral hygiene. Apparently, the 19th-century sociologist Auguste Comte became so disturbed about the manner in which his brain had become stuffed with extraneous material that he refused to expose it to any written material that was not wholly relevant to the development of his philosophy.

On the face of it, this has a certain appeal. Many of my friends already monitor what enters their mouth with all the assiduity of a Pharaonic food taster, so surely it makes a certain amount of sense to bring the same degree of discrimination to bear upon fatty brain inputs?

I’ve started slowly by rigorously refusing to read the sides of cereal packets, the Travel and Escape sections of two Sunday newspapers, a biography of Jamie Carragher which my sister thoughtfully sent for Christmas, and all those bits on the back of menus which tell you the type of cows from which the restaurant gets its steak.

So far my brain has given no sign of knowing that it’s on this special diet. But there are promising signs. Only the other night it sat quietly through an entire performance of Handel’s Messiah without once going back to Liverpool’s appalling second-half performance against Arsenal and it also showed me no signs of restlessness when I followed this with a long supper with Geraldine in which almost the sole topic of conversation was her current ambivalence about installing low-energy light bulbs.

But if this regime fails to bring my brain to heel, then I may have to take a more confrontational route. According to that neuroscientist I heard on the radio it is now possible to look at a real-time picture of your own brain functioning. You can, for example, think about sex or tell a lie or make an apology and then watch as the appropriate part of the cortex lights up.

I know exactly what I’ll do when I get the chance to use the apparatus. I’ll read out that passage from Lacan which my brain so churlishly refused to comprehend. One little flicker of recognition and I’ll know I’ve got it bang to rights.