As a teenager I rather looked forward to being old. Really old. It was all down to Wilfred Pickles. In our house we never missed an edition of Have a Go, a radio quiz show in which Pickles would invite ostentatiously ordinary people up on stage, ask them a series of simple questions, and then reward them with a small prize (“Give them the money, Mabel”). The highlight of the show for me was the moment when our Wilfred turned to a contestant and asked, “And how old are you, love?” “I’m seventy-two,” the contestant would wheeze. “Really?” Pickles would marvel. “Give him a big round of applause.” And the studio audience responded with gusto. Well done. Well done for being over 70 and still alive.

As a teenager I rather looked forward to being old. Really old. It was all down to Wilfred Pickles. In our house we never missed an edition of Have a Go, a radio quiz show in which Pickles would invite ostentatiously ordinary people up on stage, ask them a series of simple questions, and then reward them with a small prize (“Give them the money, Mabel”). The highlight of the show for me was the moment when our Wilfred turned to a contestant and asked, “And how old are you, love?” “I’m seventy-two,” the contestant would wheeze. “Really?” Pickles would marvel. “Give him a big round of applause.” And the studio audience responded with gusto. Well done. Well done for being over 70 and still alive.

It was, therefore, something of a disappointment to find that there was no audience anywhere in sight when I finally reached the average age of a Have a Go contestant. Being over 70, it seemed, was no longer a cue for applause but a sign that it was time to quit the stage altogether. I soon found that I was spending more time trying to conceal my real age than using it as credit card.

But then something odd began to happen. I began to receive a surprising number of unsolicited compliments.

It was easy enough to spot the change. I can only too readily recall the very few occasions in the past when I’ve been singled out for praise. There was, for example, that exceptional moment at drama school when my improvisational dance was described by Mrs Oliphant as “daringly original” and the equally unforgettable occasion when the stand-in critic on a popular daily newspaper referred to the “contagious enthusiasm” I’d displayed during a half-hour programme devoted to the vicissitudes of terminal depression.

But now I was suddenly finding it hard to keep count. “Greatly enjoyed your appearance on The One Show,” emailed Andy. “I called Tessa in from the garden to have a look but by the time she’d put down her trowel they’d moved on to an item about someone swimming with conger eels.”

In another email, which arrived only days afterwards, Gloria Potter was equally fulsome about an address she’d heard me give to the National Association of Deputy Head Teachers and Allied Trades at the Holiday Inn, Leicester. “You certainly hit the spot with your remarks about the challenge of change,” she wrote. “And your joke about the psychoanalyst and the man who thought he was a dog is still doing the rounds in our staff room.”

And then almost by the next post came a long letter from a former student called Eric Dunford who, after telling me about the full and rewarding life he was now enjoying as a probation officer in Middlesbrough, went on to say that my lectures on functionalism’s inability to deal with social change had remained “a constant inspiration”.

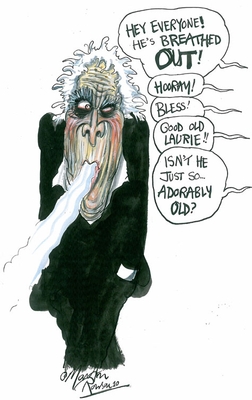

At first I dismissed this small avalanche of praise as mere coincidence. But I finally had to allow that I was in the presence of a quite new phenomenon when a former BBC producer accosted me as I was leaving The French House in Soho last week. For a second he simply stood directly in front of me without speaking. But then he clasped me round the shoulders, looked me straight in the eyes and said, “Well done, Laurie.”

“For what?” I asked. “For everything,” he said, and turned back to his mates.

I could, of course, choose to regard this enormously pleasing development as merely a long delayed recognition of my achievements. But I’m afraid there’s a far more plausible and less flattering interpretation. It occurs to me that my colleagues and friends have suddenly noticed that I’m rapidly nearing my sell-by date and that unless they issue some congratulations immediately they may have to reserve them for the time when they’re called upon to say a few words at my funeral. Why not be insincere now rather than waiting until the moments before the celebrant presses the eternity button?

Not that all my past acquaintances have yet learned to play the game. Only a few weeks ago I received an email from another ex-student who noted that in a recent radio programme I’d described myself as “glad to be here”. “I would have thought,” he wrote with what I thought was quite unnecessary capitalisation, “THAT AT YOUR AGE YOU’D BE GLAD TO BE ANYWHERE.”