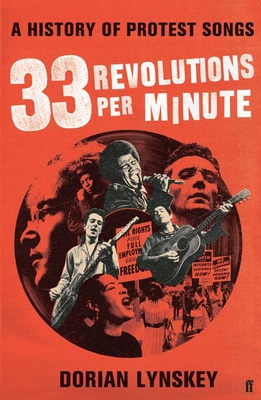

33 Revolutions Per Minute: A History of Protest Songs by Dorian Lynskey (Faber, £17.99)

33 Revolutions Per Minute: A History of Protest Songs by Dorian Lynskey (Faber, £17.99)

Phil Ochs thought longer and harder than most about what it meant, and what it mattered, to be a protest singer. “A protest song,” he once decided, “is a song that’s so specific that you cannot mistake it for bullshit.” Not for the first or last time in his wretchedly brief life, Ochs was pugnaciously articulate, arrestingly forthright and entirely wrong.

As Dorian Lynskey’s glorious, hilarious history of the protest song demonstrates, protest songs can be any or all of opaquely non-specific, prone to misinterpretation, and utter bullshit. They may also be dazzlingly eloquent, irresistibly purposeful and enduringly magnificent. Ochs, whose fierce, disappointed ghost haunts the early chapters of this book, was much nearer the mark when he observed: “One good song with a message can bring a point more deeply to more people than a thousand rallies.” It is likely that everybody reading this will be able to locate a personal memory confirming this as truth, an equivalent to Bono’s recollection, quoted herein, that “The lyrics of Joe Strummer were like an atlas. . . they opened up the world to me.”

Bono and Strummer both figure among the writers of the 33 songs that serve as chapter headings (specifically, U2’s “Pride (In The Name Of Love)” and The Clash’s “White Riot”). Where a less ambitious and able writer might have contented himself with cranking out a potted biography of each song, Lynskey uses each track as starting marks for extensive, thoughtful, beautifully written and often wryly funny rambles around a theme. So, just as The Special AKA’s “Free Nelson Mandela” is unravelled into a history of pop’s crusade against apartheid, so Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddamn” is cast in its context of America’s Civil Rights struggle, and The Dead Kennedys’ “Holiday In Cambodia” serves a cipher for a consideration of the ongoing, unresolved conflict between the punk and hippy traditions of dissent.

The ultimate result is an expansive history of the period from 1939 to the present day, set to a fabulous soundtrack, peopled by an uninventable cast of characters and riddled with delectable anecdote (although those who hold Marvin Gaye in especial regard may be better off not knowing his means of clearing his head immediately prior to recording). Lynskey deftly negotiates the delicate balance of according great art its proper respect, while remaining alert to the fact that the qualities of a song are not inevitably reflected in the singer. His writing is the more astute, and much the more amusing, for disdaining the temptations of mindless hyperbole or gratuitous abuse: this is not the work of someone who bestows either garlands, or volleys of tomatoes, without due consideration.

The book’s reach is global, including diversions to Victor Jara’s Chile, Fela Kuti’s Nigeria and Max Romeo’s Jamaica. Such is Lynskey’s command and confidence that when the book’s energy fades towards the end, in the chapters concerning the 1990s and beyond, it feels deliberate, a implicit acknowledgement that the protest song itself is slouching into redundancy (though Lynskey tries gamely, he’s unlikely to persuade anyone sane that Huggy Bear’s “Her Jazz” or Green Day’s “American Idiot” have the merit or the impact of Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land”). When Europe faced genocide on its borders in the 1990s, barely a voice was raised. Musical responses to September 11th and all that has followed it have been few, and largely feeble, and Lynskey explains why in a brilliant dissertation on Steve Earle’s “John Walker’s Blues”.

Anyone with any interest in rock ’n’ roll or politics will find multitudes to enjoy here: would that all books about rock ’n’ roll were so intelligent, and all books about history such fun.