I was in Aalborg, Denmark the day West Ham got relegated. As I boarded the plane bound for London, I checked my iPhone to discover that we were 2-0 up away at Wigan. Victory would give us a glimmer of hope that we could, once again, avoid relegation from the Premier League by the skin of our teeth. I switched off the phone and snoozed a strangely contended snooze all the way back to Stansted, buoyed by this improbable turn of events. Just over an hour later we landed and I switched my phone back on to discover that we had lost 3-2, we had been relegated with a week of the season left to play and the manager had been fired.

I was in Aalborg, Denmark the day West Ham got relegated. As I boarded the plane bound for London, I checked my iPhone to discover that we were 2-0 up away at Wigan. Victory would give us a glimmer of hope that we could, once again, avoid relegation from the Premier League by the skin of our teeth. I switched off the phone and snoozed a strangely contended snooze all the way back to Stansted, buoyed by this improbable turn of events. Just over an hour later we landed and I switched my phone back on to discover that we had lost 3-2, we had been relegated with a week of the season left to play and the manager had been fired.

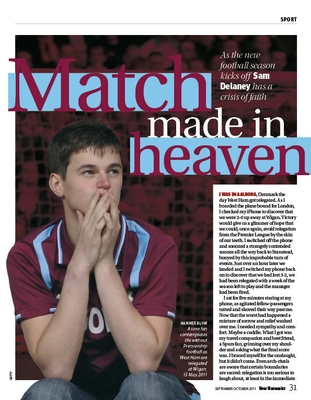

I sat for five minutes staring at my phone, as agitated fellow-passengers tutted and shoved their way past me. Now that the worst had happened a mixture of sorrow and relief washed over me. I needed sympathy and comfort. Maybe a cuddle. What I got was my travel companion and best friend, a Spurs fan, grinning over my shoulder and asking what the final score was. I braced myself for the onslaught, but it didn’t come. Even arch-rivals are aware that certain boundaries are sacred: relegation is too serious to laugh about, at least in the immediate aftermath. He patted me on the back and said nothing.

Then I roused myself to deliver a defiant speech: it all made no odds to me, I told him. I’d be back next year, just like any other. I’m loyal; I’ve got faith in my team and a love for the colours. West Ham is a family and small trivialities like defeat and relegation are not enough to change that. I think he bought it. What was weirder was that I bought it too. Relegation really didn’t matter. And by extension, nor did results. In which case, I wondered, what really did matter? If the answer was nothing, then why the hell was I bothering to go in the first place?

As a younger man I had watched West Ham being relegated twice before and had cried with despair and humiliation. But this time round, with age, wisdom and the power of reasonably sober reflection on my side, I felt humbled. Humbled by recognition that winning or losing wasn’t really the point in football. A blind faith in something outside the banalities of rubbishy old real life – with its grim procession of work stresses, relationship issues, gas bills, stubbed toes and mislaid remote controls – was the driving force behind my ridiculous, irrational and unquenchable obsession with this crappy team from east London.

Blind faith is not something I ordinarily go in for but, really, there is no convincing rationale for me to follow West Ham. It doesn’t bring me any material benefits, quite the reverse. I must have spent tens of thousands on watching the grotesque carnival of pandemonium that has constituted West Ham’s history over the past three decades. And what do I gain emotionally or mentally from my commitment to the club? Near-constant disappointment and misery punctuated by all too fleeting moments of joy. Surely if I’d wanted that kind of empty spiritual ordeal encumbering my existence I could just go to church: at least entrance is free.

I’m not the first to make this comparison, of course; there are plenty of fans – members of the club-crest-tattooed-on-their-inside-lower-lip brigade – who will proudly declare that football is their religion. But I can’t say I’m proud of the fact that my love of West Ham is the one area of my life in which I merrily gather up my usual guiding intellectual principles – reason, rigour, empiricism, the studious avoidance of processed meat products and daytime binge drinking – and dump them all in the bin.

I know that football doesn’t matter. I know the rage, the prejudices, the romanticism and the heartache it elicits in me are artificial and, all things considered, has a negative impact on my life and personality. And yet I need it for the same reasons that some people (many of whom are doubtful about the very existence of the God they worship) need religion. It’s a release from the tribulations of normal life – an emotional narrative for us to follow that has no real consequences because it doesn’t actually exist (not that I’m saying West Ham doesn’t exist, of course. I’ve been there. I’ve seen it. Even my imagination couldn’t have conjured the stench of those toilets). But the ups and downs that the club generates inside me – the euphoria, anxiety, remorse and redemption – are based on something that is every bit as real as the gods at the heart of religion. That is to say not real at all.

I had this epiphany looking over West Ham’s new fixture list, where names like Doncaster Rovers and Burnley have replaced those of Manchester United and Liverpool. I realised that it doesn’t really matter if you’re winning against Brighton and Hove Albion or Barcelona; the little thrill of victory, that totally irrational sense of one-upmanship over the opposition, is equally intense. The relative experience of victory and defeat remains more or less the same.

It would be nice to think that I could enjoy football without all that partisanship and prejudice. But the truth is the demented rivalries are the most essential part of being a fan. There are those who say the game can be appreciated on a purely aesthetic level, but they are almost always posturing liars (or Arsenal fans), or people who haven’t seen enough football in their time. If they had, then they’d know that 90 per cent of all football is crap; and not just the lower league stuff where people can’t even kick the ball properly. At the higher levels players have become so technically adept they have eradicated the sort of calamity that is the essence of footballing entertainment (England internationals excluded, obviously). Just as religious acolytes devote themselves to their gods in search of transcendent moments that rarely – if ever – come, football fans sit through years of artless hoofing in the cold and rain in hapless anticipation of witnessing a Lionel Messi wonder goal. (Only to be in toilets when it eventually happens.) Football without contrived hostilities and nasty songs, like religion without schism, is nothing.

I’m not trying to be superior to believers, my blind devotion to West Ham makes me as irrational as the next man, but at least I am aware of how irrational I am. And that my decision to subject myself to it all is now a conscious one – a way to navigate through parts of the human experience which rational thought cannot. And also to, y’know, get out of the house once in a while and have a few beers with my mates (again, like church, though for “beer” read tea).

All I wish is that it was possible to reconcile the passion and excitement I derive from football with a desire to be less pointlessly hostile to Chelsea fans.