To Sarah, all religion is mumbo-jumbo, and her lack of faith is matched only by her total lack of interest. Lying in bed one night, I asked her who she thought wrote the Bible. “I don’t know,” she said. “Some shepherd, or something.”

“What shepherd?” I asked.

“Ben Nazarus,” she said. “Or Ben of Nazarus. Nazarus was near Bethlehem. The Three Shepherds followed the Star of Nazarus, didn’t they?”

We laughed, because our differences don’t matter to us. I enjoy how little Sarah knows about the outlandish creeds of Sunday School dogma, just as she is amazed by my ability to recite the Lord’s Prayer without hesitation. But the prospect of marriage does funny things to couples.

We were eating cake in a local café when everything started to unravel. Sarah’s friends were visiting for the weekend and, as potential bridesmaids, they wanted to glean some details about our Big Day. “It's not going to be a church wedding, is it?” one of them asked. My betrothed and I exchanged awkward glances. The thing about asking someone to marry you is that you are so preoccupied with the whole proposal and getting engaged part of things that you sort of forget how it all inevitably leads to a wedding, with a dress, flowers and, top of the list, a location. Somehow, neither of us had seen this coming. “We haven't really discussed it,” Sarah admitted. “But Dom’s a Christian.”

Dom’s a Christian. Now everyone in the café was staring at me. “Look,” I snapped, shaking my head while trying to raise a reassuring smile, “I’m really not a Christian, or anything like that, but the thing is... Well, it's my mother. I wouldn't want to upset her, and... In my experience, weddings happen in churches, don't they? Besides, it's not really my decision. It's Sarah's day, so I'm happy with whatever she wants.”

I may as well have said, “Hi, my name's Dominic, and I'm a polygamist.” Our tea-and-cake session rapidly descended into a triangulation of crossfire. “What do you want, Dominic?” “What, exactly, do you believe?” “Do you need God as your witness?”

I shifted uneasily in my school chair. After stalling for 35 years, I was now, at last, being forced to declare my beliefs. My appetite lost, I took a deep breath and offered the only explanation I could think of…

I was 12 years-old when I strode into my family kitchen and expressed a desire to be confirmed into the Church of England. My mother was standing by the stove, beating some pastry with a rolling pin. “Oh really,” she said, turning to face her only son. “Are you quite sure that you are ready?” Ready? I thought. Ready for what? What the Hell is she talking about?

Plotting my annunciation in my bedroom, I had envisioned being showered with Christian goodwill, maybe even gifts. I thought that I was telling my mother what she most wanted to hear, but even with her back turned, she saw right through me. My catalogue of recent crimes was forcing her, no doubt, to wonder for which particular act of delinquency I was now trying to atone. Only the week before, she had been called into my school after I had locked my maths teacher inside a cupboard. The week before that, I had been picked up by the police for joyriding – in a shopping trolley. When the officer asked me for my name and address, I had told him that I was “Barry Manilow. Of Beverly Hills.”

Moving away from the fridge, I laid hands on my mother's shoulders. “I think we both know that it is time,” I said, sighing for effect. “Plus, I really feel – in my soul – that this is what God wants from me.”

I shall never forget the look on her face. “’God’?!” she said. “What do you mean, 'God'?!”

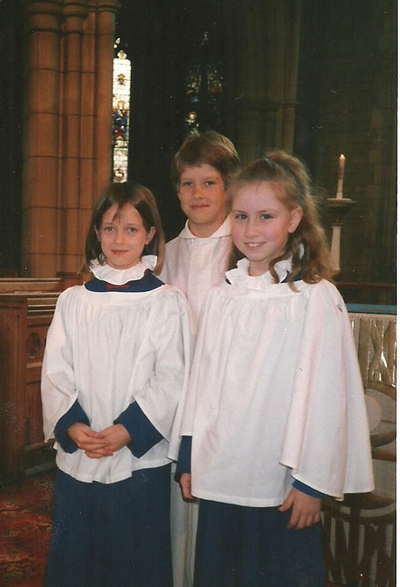

I had no idea, as my mother well knew, what "being confirmed" meant, no more in theory than in practice. I still don't; but I didn't care back then, because I saw confirmation as the quickest way out of having to wear dresses.

The Church had been forcing me to wear dresses ever since the dark day that I was christened. By all accounts, my baptism had been an unmitigated disaster. Stuffed into a heavily-starched, frilly gown, I howled my way through the entire ceremony. “I was ashamed of you!” my mother says to this day. “And so was everyone else.”

Confirmation, I had decided, was my ticket out of this cross-dressing mess – a glorious opportunity to slip out of my robe and into my shiny, silver, double-breasted New Man suit. I planned to pair the suit with some slip-on, tassled loafers, and then I planned never to look back. No more duties; no more dresses.

But though my mother was a staunch church woman I was subject to countervailing influences. Dad – a communist by his own reckoning, though a manager in a global arms corporation by trade – called himself ‘agnostic’, a word I accepted but never bothered looking up. “If I was going to be religious, I'd go the whole hog!” he would boast. “Become one of those self-flagellating monks. Or join the Mujahadeen!” I saw his point. The Church of England was spectacularly uncool, comprised, in the main, of the halitosis-impaired and boffins who twitched. My father called it “the Tory party at prayer,” a phrase I thought he had invented to annoy my mother, until I heard other kids using it at university and wondered how they knew my dad.

But his wilful godlessness never really played with me, perhaps because I always saw religion as more romantic than... whatever the alternative was. I liked how Madonna wore crucifixes. I loved how Latin footballers crossed themselves before running onto a pitch and after scoring a goal. Religion was just so stirring. Even now, I can't listen to Bruce Springsteen sing about God's light falling across his sleeping wife's face, or hear Jay-Z thanking the Big Guy for his momma's unconditional love and support as he moved snowflakes by the O.Z., without getting all emotional and thinking something along the lines of Praise Jesus!

The reason my mother goes to church is not to pray for the Queen or for the Bishops – I know that stuff is just a front, a way for emotionally-retarded Anglicans to cloak their real feelings. No, the reason my mother goes to church is to pray for us, her family. Membership of the Church of England is her peculiar way of showing her love for us, and to fail to return the favour feels a bit like slapping her in the face, akin to telling her that, grateful as we are, that love is not reciprocated. And it is this lazy, slightly screwy rationale that pretty much saw me through, until I got engaged to be married, and suddenly “Jesus Christ was a righteous dude – and besides, don't you just wish it was all true?” would no longer wash.

“What do you want, Dominic?” “What, exactly, do you believe?” “Do you need God as your witness?” Not even my mother had ever asked me what, if anything, I really actually believed, just as I had never asked her, and neither of us had ever asked the Vicar. I was caught in a turkey shoot.

We exited the café, my approval ratings flagging, and I found myself thinking about something my parents always used to say. “We intend to raise children with open minds.” It was their excuse for everything. Whatever embarrassed or humiliated their offspring was, by definition, doing us good. My father used to delight in picking me up from football practice, Gotterdammerung or The Rape of Lucretia blasting from the sunroof of his company saloon. If his kids weren't performing in some musical recital then they were being dragged to some avant garde dance performance. "Do we have to watch some freak prance around in the nude?" my sister would wail from the backseat of the car. Dressed in an itchy, starched shirt, I would let her rest her head on my shoulder. I liked how the tears softened my collar.

For my mother, though, having an open mind meant something else entirely. The two things she could never stomach were quitters and sheep, and she still has a hard time distinguishing between the two. The Church was perfect in this regard because Christianity was in decline, which made us Christians a persecuted minority. In her worldview, the atheist orthodoxy reeked of the mindless herd, the faceless mass, the same unruly mob who had condemned the Son of God to the crucifix. My sister and I were distinguishing ourselves, raising our heads above the pulpit. "If you quit going to church," my mother was telling us, "then why not just quit on the sports field, too? Why not just quit in life? Why not just be a quitter?" Going to church was never about reciting the scriptures. It was not even about God. It was about resisting peer pressure.

I think this is why I have such a hard time letting go now. I want to think for myself, even if it means suspending all reason.

Which is why, after her friends had left, I turned to Sarah and said, “It's harmless, I promise. It's the CofE, not the Taliban.” And this is how we ended up attending the christening of my second cousin in a small hamlet in Derbyshire. Much of my extended family were in attendance and the reception was hosted in an orchard at my cousin's thriving equestrian centre just up the lane from the thirteenth-century church. My parents had driven us the day before, my mother talking pointedly about her Godly duties most of the way up the M1. I suspected her of ulterior motives, but I said nothing. Though my sister had wriggled out of coming, Sarah had decided to give it a go, the same way that I had let her read me my birth chart.

As we pulled up at the church, I looked out of the window of my father's SUV at my relatives, loitering in the graveyard like the members of a rugby club on their annual trip to Ascot. We said our hellos, and I introduced my fiancée. Then, summoned inside, we chaotically made our way through the south entrance. As we were handed the order of service by a warden who bore a chilling resemblance to a mentally ill patient on day release, Sarah whispered into my ear, "This is only my third time inside a church." I froze: "Ever?" "Yup, ever," she smiled. I failed to see how such a thing was possible; but from that moment on, I could only witness the whole experience through her increasingly wide eyes.

Other religions were mad. That’s what I had always told myself. Hasidic Jews grew corkscrew curls so that God could pull them up towards Heaven, leaving behind those of us with short back and sides. In Jerusalem, I had tried to interview some of them as they wasted fourteen-hour days rocking back and forth on their heels inside caves, reading from the Talmud to an unresponsive damp wall. Islam forbids using the left hand to eat and drink. The International Society for Krishna Consciousness runs up and down the Tottenham Court Road. The Anglican Church was dotty, perhaps, in the quaint Miss Marple sense, but biscuits were banned in my household on calorific, not religious grounds.

Then the service began, with an obscure and disjointed hymn about virgins. The organist hit all the wrong notes, and the only person really singing was my mother, who was singing far too loudly. Nobody seemed to be facing the same way. Old men were picking their ears. Toddlers were running riot. A woman in front of me was holding her hymn sheet upside down.

It was a nuthouse. The Vicar had three teeth and two wisps of hair in the style of Devil's horns. He stammered badly as he stared into the rafters, his head always half-cocked, like a man swilling olive oil around his eardrum. Much of what he said was repeated just moments later. "Christ" came out as "Cwyst". He spat over the front row of the congregation and, as Sarah put it, "He didn't seem to know where he was." The most important lesson in life, he said in his sermon, was to never, under any circumstances, question the mystery of faith, ask any questions, or seek out any evidence for God's existence… because there is none.

Interspersed between stories of the good Lord's merciless wrath were reminders of next week's tombola. As the service progressed, the hymns got longer, weirder and less singable, and then, after the Vicar had polished off the wine, everybody gathered around the font where water was inexplicably thrown over an infant's head. I glanced at Sarah, and tried to suppress the ignoble feeling that this was righteous payback for the time she dragged me into The Astrologer's Bookshop in Covent Garden. Afterwards, back in the graveyard, she slipped on her sunglasses and said, "You think that's normal?"

There was a rumour that Dr. Clements had fathered twenty children. Twenty. I first heard it from a girl who told me that she had heard it confirmed by Clements himself, in front of her class, but I didn't believe it. Who has twenty children? "Ask him," my friends said. "Find out for real." So, one afternoon, as Dr. Clements was trying to read to us from the Gospel according to John, I raised my hand. "Sir, is it true that you and your wife have twenty children?" I don't know what I was expecting. Another detention, perhaps? (I was already sitting alone behind a desk at the front of the class, as punishment for previous crimes.) But Clements merely adjusted his 1950s spectacles over the top of the Bible. "Yes," he said, "it is true." I turned to look at my classmates and then I turned back. "Why, sir? I mean, why do you have twenty children? What for?" Again, I don't know what I was expecting, but it certainly wasn't the answer that I got. "I have 20 children," Dr Clements said, "because if nine of them died in a coach crash, then I would still have enough for a football team."

A few months later, Dr Clements tried to kill me. For a homework assignment, I had penned a controversial modern take on the Devil's failed temptation of Christ in the desert. In my version, the Devil had tried everything, including dressing himself up in garter belts and hosiery. The dialogue was littered with doubles entendres of the most juvenile kind. Clements made it through the first paragraph and a half, and then leapt over his desk and chased me around the room with a wooden metre rule. In between threats of murder came dogmatic accusations of blasphemy. I had to think on my feet. "But I go to church!" I yelped in my defence. "I'm about to get confirmed!"

Clements pulled up like a horse startled by a snake. "What did you say?" I leant against one of the desks to catch my breath. "I said I'm getting confirmed. You know, into the Church!" The metre rule clattered to the floor. “’The Church’?” Clements croaked. “’The Church’?! But why?” There was only one thing to say. “I really feel – in my soul – that this is what God wants from me."