In the House, Liberal Democrat science spokesman Dr Evan Harris raised concerns that the evidence in the report had not yet been published – and could therefore not be properly scrutinised. Harris cited the fact that the Royal College of Nursing had expressed concern that further criminalisation could actually be counterproductive, driving victims of sexual exploitation further underground, and away from where they might seek help. There was, Harris argued, a need to examine more thoroughly the evidence on which the proposed legislation was based. “We are looking at publishing the evidence,” replied the Minister, but “in the end, you pick the evidence which backs your argument.”

To those familiar with the scientific method this cherry-picking of data to support a preconceived hypothesis is a hallmark of quackery. Watching the debate, “mouth agape”, was Harris’s Parliamentary researcher, and biology graduate, Imran Khan. Khan was astonished that a government minister could think about, or talk about, scientific evidence in this way. He is now Director of the Campaign for Science and Engineering (CaSE), a lobby group for science and technology education, and cites this tale as a textbook example of “policy-based evidence-making” – when evidence is chosen only to support or defend an already decided policy. Khan is one of a growing cadre of scientifically literate activists who see it as their job to root out this kind of back-to-front thinking, and to promote instead “evidence-based policy-making”, where rigorous, reputable and, crucially, publicly available evidence plays more than merely a fig leaf role in public policy. These include prominent public figures like Khan’s old boss Harris, who writes the Political Science blog for the Guardian, science writer and scourge of the chiropractors Simon Singh, and the Guardian’s Bad Science columnist Dr Ben Goldacre.

Pushing in the same direction is Sile Lane, Campaigns Officer of the pressure group Sense about Science, which has recently launched the “Ask for Evidence” campaign. Whenever a company, journalist or politician makes a seemingly dubious scientific claim, Sense about Science says we should demand to see their evidence. The campaign is backed by a broad coalition of patient groups, scientists, journalists and celebrity supporters. “We’ve been working with scientists and the public for years,” Lane told me, “to challenge misinformation, whether it’s about homeopathy for malaria or the causes of cancer and wi-fi radiation.” Like Imran Khan, Lane believes that public engagement is the key to improving the situation – if politicians, PRs and journalists start to see that the misuse of data or citations of dodgy evidence are routinely challenged by the public, “policy-based evidence” could become a thing of the past. “Imagine a world,” Lane says, “where every exaggerating scientist, or politician, or company, or advertising firm, or someone writing on the internet, or journalist expects to be asked for the evidence behind every claim they make. That will make them think twice.”

It sounds good, but is it a realistic outcome? And, if we want public policy to be guided by values, is it even a desirable one? After all, this is not the first time we have heard the benefits of evidence-based policy trumpeted. It’s worth reviewing the recent history of the term.

The idea of “evidence-based policy” has its roots in “evidence-based medicine”, a term introduced into the medical literature in 1992. Writing in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Canadian epidemiologist Gordon Guyatt described a “new paradigm” in medicine which “de-emphasises intuition [and] unsystematic clinical experience as sufficient grounds for clinical decision-making and stresses the examination of evidence from clinical research.” Advocates of evidence-based policy sought to extend this principle to decisions in the political realm.

They had early success. Evidence-based policy became something of a leitmotif in the early days of the Blair government, according to economist Nigel Meager, who has served as an adviser to three Parliamentary Select Committees and is now Director of the Institute for Employment Studies. “The Labour government paid a lot of lip service to evidence-based policy-making and spent a lot of money collecting the evidence,” he tells me. “Yet it’s hard to show that all of the evidence gathered during those years really fed into policy in an identifiable way.”

This fad for evidence yielded few positive results, Meager argues, for a variety of reasons. Studies were often poorly conceived and cumbersome, leading to long delays between the commissioning of studies and the delivery of their findings, which would mean that in many cases ministerial interest would have waned and policy objectives been rethought in the interim. Sometimes, also, “the evidence gathering itself was not terribly scientific.” Enthusiasm for the new age of evidence would also mean that perfectly valid research from the past would be overlooked. “Anything that was outside the recall of the current cohort of civil servants or that wasn’t quickly Google-able was not included in the evidence,” says Meager. A “classic example” was the 2006 Leitch Review, which looked into the UK economy’s “skills base”. This produced “lots of interesting conclusions about how badly we were doing compared with our international competitors, and a number of policy prescriptions. But [these were] almost identical conclusions to a similar study that was conducted by the National Economic Development Office in the 1980s.”

Part of the problem was the technocratic assumption that evidence-based policy provided a way to move beyond ideology. No longer based on out-dated moralistic “oughts”, New Labour’s policy would be grounded in “what works”. For Meager this was a pipe-dream: “The questions that the evidence is being tested against [are] always politically driven. The idea that we’ve moved from ideology-based policy-making to evidence-based policy-making, into a purely technocratic world, is completely misleading, because the evidence-gathering process is itself value-laden.” Not only is this a political reality, it should also be welcomed by those who believe that what our government does should be guided by political and moral principles, rather than pure pragmatism.

Another, and opposite, problem was that the much vaunted commitment to the evidence only went so far. Coaker’s gaffe was just one example. It was a Labour Home Secretary, Alan Johnson, who in 2009 provoked one of the biggest science policy controversies of recent times by sacking an independent expert, Professor David Nutt, from the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Nutt’s position was voluntary and unpaid, his job to provide frank and objective policy advice based on his scientific knowledge. Yet when the Professor criticised the government’s decision to recategorise cannabis from a Class C to a Class B drug, and argued that drug classifications should be based solely on the evidence of the harms they cause, the Home Secretary had him removed from the advisory council. Opinion polls indicate strong public opposition to any relaxation of the drug laws, including the downgrading of cannabis. Opponents of decriminalisation insist that heavy penalties are needed, in order to “send a message” that the use of drugs is morally wrong. New Labour’s putative commitment to “what works” was trumped in this case by the need to stay in line with public opinion.

Have today’s advocates of evidence-based policy absorbed these lessons? It sounds like they have. “We’re certainly not arguing that things that are matters of political judgement or ideology should be matters of evidence-based policy,” Evan Harris insists. “Of course there are some things which are simply not capable of an evidence-based approach, or where the evidence-based solution is legitimately blocked, because of ideology or the need to keep manifesto commitments. That’s legitimate, as long as it’s clear.” For Harris it is a matter of distinguishing between policies where it is appropriate to look for a foundation in ideology, and those where evidence should take a leading role: “[I’m not going to] have an ideological approach to the safety of nuclear materials, or how I’m going to build this bridge, or how I’m going to protect children from serious illness. In those sorts of areas it would be ridiculous to take a recommendation – even if you were transparent about it – if it went against the evidence, because vulnerable people’s lives are at stake.”

Another distinction that seems vital is that between the kind of reliable data that might underpin, say, analysis of the effects of a new drug treatment or energy source, and the kind of data you might get relating to less clear-cut issues like people’s behaviour. This is the distinction between “hard” and “social” science. When we are talking about evidence as it relates to social policy, in terms of both justifying a particular policy and assessing its impact, there are particular problems.

“One difficulty”, according to Mark Newman, a reader in evidence-informed policy at the Institute of Education, “is that social science doesn’t really fit with the way the government likes to make decisions. A social scientist does a pilot study, with the full anticipation that they will learn something from it, including ‘this is not the way to do it’. After a pilot you might scrap the idea altogether. But this doesn’t appear to be the way that policy-makers think of pilots. They think of it as ‘you might learn something about how to implement it, smoothing out the rough edges’, but opening up to the possibility of ‘actually that doesn’t work at all, we need to go back to the drawing board’, doesn’t seem to be a possibility. Politicians don’t want to have to admit that they’ve made the wrong decision. There is a culture of policy-making where the politician’s job is to come up with a solution and it will work. Whether it really works or not is irrelevant. It will be shown to have worked in some way or another.”

In addition to this culture clash, there are practical problems of scale and complexity that can make producing accurate evidence in relation to a policy extremely difficult. Take the recent proposed reorganisation of healthcare. Health Secretary Andrew Lansley plans to roll reforms out in all areas simultaneously, but this, according to Mark Newman, “makes it very difficult to have a rigorous evaluation of its impact because you don’t have a control group”. In the absence of reliable evidence of the actual impact of reforms such as these, the question becomes: what evidence is relevant? And, as in this case, both sides can appear to be arguing the “evidence-based policy” line, though they disagree about which evidence matters, or the validity of particular research. Each accuses the other of not playing fair with the scientific data. Thus the Guardian’s Ben Goldacre wrote a series of articles questioning the government’s case for its reforms. While the Health Secretary Andrew Lansley insisted there was good evidence that replacing Primary Care Trusts with GP consortia to commission patient services would improve the quality of care, Goldacre saw “no evidence to follow”. Studies of comparable models were thin on the ground, he said, and those that did exist – primarily focusing on “GP fundholding” – had found no evidence that commissioning services in this way had led to significant improvements. “I have never heard one politician use the word ‘evidence’ so persistently, and so misleadingly, as Andrew Lansley,” Goldacre commented.

Liberal Democrat health minister Paul Burstow responded by citing an impact assessment which he said showed that GP fundholding had reduced waiting times and hospital referrals. Burstow also highlighted a 2008 paper which he claimed showed that “the UK had one of the worst rates of mortality amenable to healthcare among rich nations”. Goldacre hit back, charging that Burstow “either misunderstands or misrepresents this very simple and brief paper.” The government’s impact assessment, he said, had “cherry-picked only the good findings, from only one report, while ignoring the peer-reviewed literature. It’s absolutely fine if your reforms aren’t supported by existing evidence,” Goldacre concluded, “you just shouldn’t claim that they are.”

This seems to encapsulate the message of the contemporary campaigners – not that evidence should dictate policy, but that any evidence that is used should be used properly and shared openly. This theme informs all the recent campaigning, which is aimed not at usurping politics but at raising scientific literacy among the public, media and politicians. When I asked him to comment on this debate, Goldacre told me, “I think politicians often use evidence decoratively, that they think about the word in the same way that a barrister would: it’s a matter of what they can get away with.” Goldacre is not merely being metaphorical here, but has put his finger on one particularly noteworthy feature of our current parliament – the scarcity of scientists compared to the ubiquity of lawyers. Out of 646 Members of Parliament, only two have had scientific research careers, compared to more than 70 lawyers.

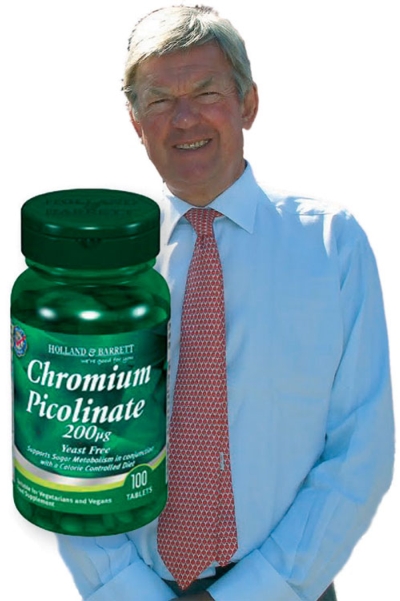

And while Tredinnick (once cheekily described by John Denham MP as “the Right Honourable Member for Holland and Barrett”) may be an extreme case, he’s by no means alone. One particularly stark indicator is an Early Day Motion published in 2007 that claims – in the face of overwhelming scientific evidence to the contrary – that homeopathy is an effective medical treatment, and urges the government to continue funding it through the NHS. The motion was signed by over 200 MPs – nearly a third of the House of Commons.

And in between the politicians and the public lies the all-important intermediary of journalism. Reporters play a vital role in communicating scientific research and new evidence to the public, and Sile Lane believes she has seen a change in culture under the pressure of campaigning groups like Sense about Science. “Six or seven years ago, science stories in the papers very rarely had a citation to a proper journal –they rarely said whether this research was published or presented at a conference or just the work of one man saying this in a press release that no one else has looked at. So we asked our supporters every time they see a story like that to ask the journalist why didn’t they include the citation The journalists began to expect to be asked that so started to include ‘published today in Nature’ or ‘presented at a conference in Amsterdam’ or whatever. It’s led to a change in the way journalists and editors and newspapers work now.”

But there are special pressures at play in journalism that may not be quite so easily overcome. “There is a fundamental tension between science and journalism,” says Claire Coleman, a freelance journalist who specialises in health and beauty, an area in which companies often make questionable claims about the benefits of their products. “Science isn’t just about definitives – it’s about ‘this thing’s based on this’ and ‘it would appear that this is the case’. Whereas actually newspapers like ‘this is this’ and when you’re being copy-edited the first thing that goes is ‘seems’, ‘it would appear’ etc. The media like things to be very cut and dried – there aren’t the shades of grey that there are in science. That’s a very difficult thing for lay people to get their head round because science is seen as very definitive. I think that most people don’t realise that scientific theories are just hypotheses which can be proven and disproven on a regular basis, hence the ‘coffee causes cancer’ one day, ‘coffee cures cancer’ the next day kind of thing.”

Nevertheless, with scientifically literate journalists like Coleman working in the health and beauty area, which can be so prone to circulating unsubstantiated PR-inspired scientific data, and campaigners urging readers to demand proof of exaggerated claims, it is less easy to get away with spurious claims than it was in the past. And back in the political sphere there do seem to be reasons to be cheerful.

While “policy-based evidence-making” continues, Imran Khan tells me, politicians are becoming “more conscious of this culture where we’re moving towards having evidence for everything”, and of the need to justify their policies in evidence-based terms. He points to the fact that, whereas the European Union is only now considering the appointment of its first Chief Scientific Adviser, the UK has a CSA position in almost every government department.

Khan’s cautious optimism is echoed by Alan Henness, of the Nightingale Collaboration campaign group, which works to challenge misleading health claims. While Henness has some doubts about the direction being taken by the new government, he thinks “the questioning of whether policy is based on sound evidence is definitely on the march and evidence does seem to have a higher profile than it has done in the past.” Nigel Meager is more cautious still. “You hear the phrase ‘evidence-based’ used much less than you used to, and research budgets are down,” he says. Yet this has had some curiously positive outcomes. “I’ve seen some evidence that spending less money on research is actually forcing civil servants to be a little more thoughtful about how effectively they’re spending their money. I’m certainly detecting a greater willingness to take account of the wealth of academic and other evidence that exists on a particular topic, rather than simply commissioning a new study.”

For some, things may appear worse, but that, says Evan Harris, is because “our expectations are much higher than they were. Therefore the gap between expectations and delivery is wider. There’s more effort made in government to walk the walk, rather than just talk the talk, such as by recognising the value of peer-reviewed publications. The evidence-based nature of policy-that-ought-to-be-evidence-based is a political issue. Evidence has a cachet – it has become a political value in itself.” We can only hope that time will prove him right.