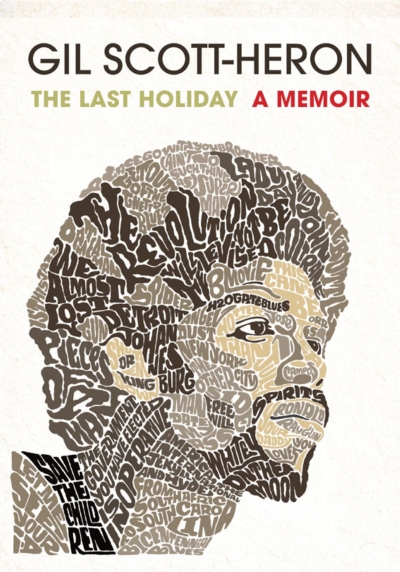

The Last Holiday by Gil Scott-Heron (Canongate)

When Gil Scott-Heron died, on 27 May last year, aged 62, none of the obituaries missed the opportunity to celebrate him as one of the “godfathers of rap”. It’s an easy case to make. His style of incendiary, unashamedly black political poetry over tight funk, on such masterpieces of agit-prop as “H2Ogate Blues” (an excoriation of Nixon), “Whitey on the Moon”, “B-Movie” (a satirical take on the election of “Ronnie Ray-gun”), anti-apartheid anthem “Johannesburg” and, most famous of all, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”, sets him firmly on the continuum between Black Power-era rap pioneers The Last Poets, and the politicised hip hop of 1990s bands like Public Enemy and rappers like KRS-One.

But merely to honour him as a forerunner of hip hop is to miss so much of what made Gil great. More than that, the association with rap is so redolent of confrontation and bravado that it risks leaves the wrong afterimage, Gil Scott Heron as a cross between Eldridge Cleaver and Chuck D, all afro and attitude, fighting the power with his soul on ice. But, as he tells us in The Last Holiday, his just-published posthumous memoir, despite what he calls his “melodic guerrilla warfare” he is not really “a political person”, he derides “posturing”, in his heart he remains a country boy from Tennessee not the ghetto, he is not tougher than leather but soft as a summer morning. Reticence becomes him far more than revolution.

The music bears this out. Listen to his extraordinary back catalogue, fifteen albums starting in 1971 with Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, an unbroken more-than-one-a-year run to 1982’s Moving Target, and the two late works, 1994’s Spirits and the surprising late flourish of I’m New Here in 2010, and it’s obvious that for every song about revolution there are five about peace, the dawning of a new day, or friendship.

Many of these are fine songs too – like “Peace Go With You Brother” – but Scott-Heron in sweet mode doesn’t quite convince in the way that, say, Donny Hathaway or Al Green can calm and salve. He was too aware of contradiction and the bitterness of being alive to do hope. Above all Gil Scott-Heron is the poet of the dispossessed and defeated – the laid-off workers, junkies, hopeless alcoholics. It’s in songs like “The Bottle”, “Home Is Where the Hatred Is” and “Ain’t No Such Thing As a Superman”, songs about people who have gone too far and ain’t coming back, that his clear-eyed appraisal of human frailty, and the part we all play in letting the weak fall, is at its most lacerating. One critic called him, in an unimprovable phrase, “a savant of the broken path”. He sang disappointment like he knew it well. He knew what it was like to be let down and to let others down. Because he did, me included.

The first time I had a chance to see him was when he played a free CND concert in Hyde Park in 1987. I was late and missed his set. Hardly his fault, granted, but the next time was. It was in Los Angeles, 1990, at the creepily named Club Lingerie on Sunset Boulevard. We came early, paid and settled down for the promised two-set show. He mumbled his way through the first set, and didn’t bother turning up for the second. The last time I saw him was in London, in the late 1990s, outside the Jazz Café, where I had just seen him do a competent, if occasionally incoherent set. As I waited outside for friends Gil suddenly appeared by my side, gaunt and dishevelled. I had a strong urge to hail him, to offer my help, to take him where he wanted to go.

But by this time his long-term drug addiction was common knowledge, and I knew I did not have the requisite knowledge of North London’s crack-house scene to get him what he needed. He ghosted away in a cab.

But I still have his records. And now, this memoir shepherded into life by Jaime Byng of Canongate, coaxed out of the reluctant, almost hermit Heron, over many years, with a cool collage of an afro’d Gil on the front, and a black power fist on the back. But despite the groovy artwork and the promise that it might, finally, throw some light on Gil’s self-destructive genius, it disappoints too, and the disappointment starts early, with the back cover blurb: “Dr Martin Luther King had a dream. Stevie Wonder had a dream. This is a book about dreams.” Not really what I had in mind.

The disappointment continues within, over 42 mismatched chapters of reminiscence and anecdote. Childhood in bucolic Jackson, Tennessee, among the strong women, mother and grandma, who raised him; a scholarship to posh Fieldston High School, where the already talented but obstreperous Gil had to sneak sessions on the vigilantly guarded grand piano, and Lincoln College, where he met black history, black literature, activism and multi-instrumentalist Brian Jackson, his long-time collaborator. It tells of his nascent years of touring and recording, becoming the first artist signed to Arista Records by impresario Clive Davis; and most of all, as in too much, of the 1981 Hotter Than July tour with Stevie Wonder, which culminated in a great rally in Washington as Wonder’s campaign to have Martin Luther King’s birthday made a national holiday came to its successful culmination. It’s not that this stuff isn’t interesting – the language is fitfully melodic and you can hear it spoken in Scott-Heron’s unmistakable tones as you read.

And it’s not that Stevie Wonder isn’t deserving of praise – his string of 1970s protest funk-soul albums for Motown are probably the era’s defining musical artefacts, out-doing, just, those of Marvin Gaye and Gil himself. It’s just that this is Gil Scott-Heron’s memoir so you want it to be an insight into him. It’s that what you really want to know is the answer to questions like: when did his occasional reefer smoking develop into a full-blown cocaine habit? And what was it like to live the last decades of his life in a dimly lit crack-pipe-strewn hovel in New York City with HIV? And why did he fall out with Brian Jackson – who accused him of chiselling him out of royalties – and how did he feel about it? And why did none of his marriages work? And what are his kids like, and why was he, as he admits, a bad father? And what was it like in prison? And how does it feel to be the most heralded voice of black American revolutionary musical transcendence and yet not be able to organise a clean shirt or remember all the words to “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”?

As you get to the messy end of a messy memoir of a messy life the disappointment threatens to overwhelm… and then, suddenly, this: “On a typically warm Los Angeles evening in 1990, we were scheduled for two shows at Club Lingerie on Sunset Boulevard.” The show I was at! Then, “As I was leaving the stage between the two shows, I suffered a stroke.” Oh.

And then, like a sucker punch, the last chapter, barely five pages, with Gil wandering his recently deceased mother’s apartment, “a refugee from the college of clowns. I was repulsed by my lifelong insistence on fucking isolation, some of it … justified by a real fear of the consequences awaiting those who befriended me and drew close … I am honestly not sure how capable I am of love. And I’m not sure why.” And this, the closing, devastating line: “I hope there is no doubt that I loved [my children] and their mothers as best as I could. And if that was inevitably inadequate, I hope it was supplemented by their mothers, who were all better off without me.”

You see then that this is a man who lived on the outside looking in. Which is why he could understand the man who “done quit his nine to five, drinks full time, now he’s living in the bottle” (“The Bottle”), or wanders “down some dead end street [where] there ain’t no turning back” (“Angel Dust”), or the basehead for whom home “was once empty vacuum, filled now with my silent screams” (“Home Is Where the Hatred Is”), or “Standing in the ruins of another black man’s life” (“The Vulture”), or the man who, when he feels “down and out and don’t know just what to do, living all of my days in darkness”, can be saved, almost, by music (“Lady Day and John Coltrane”). Gil Scott-Heron’s real memoir, his junkie life of torment and revelation and hope and disappointment, is set to music and available at all good record shops.