“So interesting,” I murmured aloud as though unable to control my appreciation. “Isn’t it?” she murmured back, hardly turning towards me. We both stood in silent contemplation for another moment.

“You know, of course, that Alan Measles is the Teddy Bear?” she said in a loud whisper. “There in the middle of the pot.”

“Oh yes,” I whispered back. “He’s Grayson’s alter ego.”

She turned to face me. “You’re obviously an admirer,” she said.

I nodded firmly. “That makes two of us,” I ventured. Over coffee in Museum Street Caroline told me that she was a “huge fan” of Grayson’s work. “You realise that he’s revolutionised pottery.”

“Oh yes,” I said.

“He’s taken something which was a mere craft, something associated with village fetes and evening classes, and turned it into an art form.”

“Oh yes,” I said.

I briefly thought of mentioning the odd Grecian urn as a small exception to her theory but she was already telling me how “wonderfully good” Grayson was at “yoking together disparate images”.

“You saw his ‘Map of Truths and Beliefs’?” A map? It sounded altogether too large for me to have missed. “Oh yes,” I said.

“Didn’t you think it was wonderful how he challenged our conventional idea of the pilgrimage by including not just Jerusalem and Mecca and Glastonbury but also Wembley and Wall Street and Nashville?”

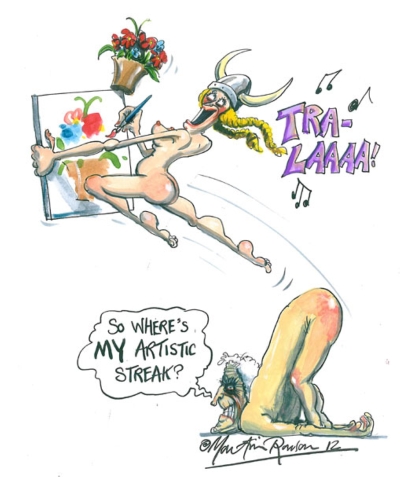

“Sort of revelling in anachronism,” I said hopefully. She nodded for me to go on. “Sort of delighting in the juxtaposition of the sacred and profane.” Another nod. “Sort of deconstructing previously incompatible categories,” I said. That was the moment when she popped the question. “Do you,” she said, looking as though she was steadying herself for news of a life-threatening condition, “do you, yourself, have an artistic streak?”

I hesitated. It wasn’t as though she was asking if I were an actual artist. I would have truthfully said “no” to that question without a second thought. But she was only asking for evidence of an artistic streak. A smidgeon of artistry. A smudge of creativity.

And that made matters difficult. For although I’ve never done anything discernibly artistic in my entire life, I’ve somehow never quite abandoned the idea that given the time and the opportunity I might well discover a modestly-sized inner muse, an ounce or two of pure inspiration, and yes, a pretty solid streak of artistry.

So, for example, even though it’s taken me the best part of two years to learn to play a passable version of “Danny Boy” on the electronic keyboard in the living room, there are moments when I start tinkering with the keys and feel that I just might be on the edge of composing a piano concerto. Not a major work perhaps but one in which the critics would detect exciting promise.

It’s much the same with my photographs. Although most of my attempts at artistry with the camera result in what a former partner once referred to as “well-focused blurs”, there are one or two studies of street life in Clerkenwell which have the flavour – I put it no more strongly than that – of early Cartier-Bresson.

But I’ve always suspected that I’m most likely to discover my artistic streak in fiction. What’s always held me back here is getting started on the first chapter. No doubt a proper artist like Tolstoy found it relatively easy to come up with the first line of Anna Karenina –

“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way” – but when you’re only blessed with a streak of artistry you can easily find yourself staring at the blank first page of your putative novel for the best part of a week.

“I thought there might be something creative about you,” said Caroline, using her little finger to check that the cappuccino had left no chocolate smear on her upper lip. “What’s your particular métier?”

“Well, you know,” I said in the tone of one who fears that their inspiration might be impaired by its mere acknowledgement. “I’ve often felt that I may have a novel in me.”

It was, I suppose, a tribute to Caroline’s basic sense of decency that a full three minutes elapsed between my confession and her discovery that she was already late for a very important meeting in quite a different part of London.

“Must make haste to make haste,” she said, briskly pulling on her coat. Not a bad first line, I thought, carefully transcribing her hurried farewell into my souvenir Grayson Perry jotter.