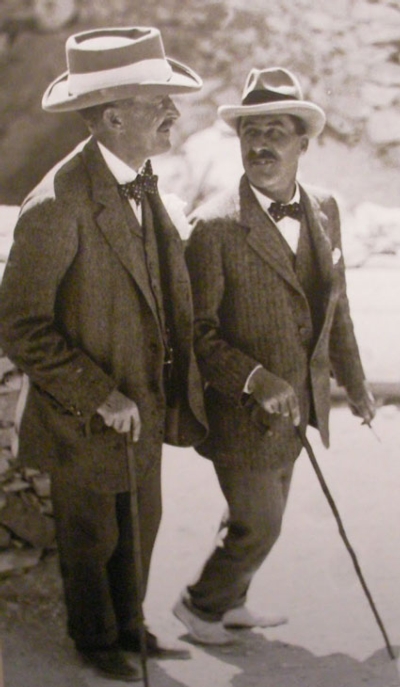

The press got hold of the story because Carnarvon himself had signed an exclusive deal with The Times to report on the findings inside the tomb. Blocked from the actual discoveries, reporters used Carnarvon’s decline from blood poisoning and pneumonia to fill their pages instead. The rumours were zapped around the world in a new era of global communication.

There were some splendid stories attached to Carnarvon’s death. The lights of Cairo flickered and failed across the city as he died. His three-legged dog Susie, back in England, howled mournfully and dropped dead. In the following days, the British Museum was inundated with mummy memorabilia offloaded by guilty tourists fearing supernatural revenge. In the next few years, over 20 people were alleged to have been killed by the enraged elementals protecting the king. The suicides, accidents and exotic diseases of archaeologists and their families were all lovingly detailed.

These reports were written in the strange tone of disavowal that accompanies many superstitions: of course this is ridiculous, but you never know. British colonial attitudes tried to associate belief in curses with the credulous and primitive Arabs that lived in a sunken state amongst august tombs that they did not understand. But it is clear this was for many of the British a displacement of the anxiety that comes with colonial occupation. Tutankhamen was discovered at the time of a handover to Egyptian nationalist government, a time of conspiracies and assassinations of British officials in Cairo. You never know what knowledge the natives might range against you.

Curse stories have always had the implacable power of rumours to sweep up everything, including denials, into their system. When the archaeologist Arthur Weigall died in 1934, the Daily Express headline was “Arthur Weigall, who denied Tutankhamen’s curse, is dead”. Within days, it was truncated and reversed: “A curse killed Arthur Weigall”.

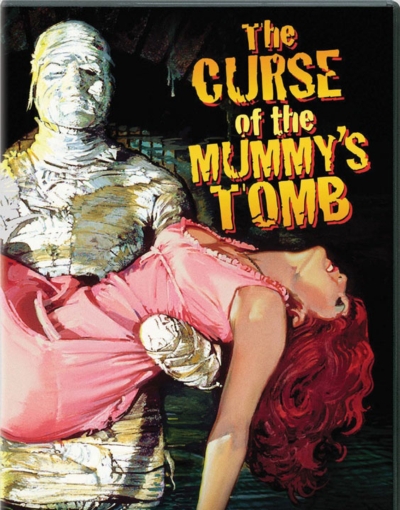

In 1932, Boris Karloff played the reanimated magician Imhotep in the Universal horror film The Mummy, and the notion of implacable Oriental vengeance from beyond the grave was fixed in place. Fact and fiction fused in a simple moral tale: if you transgress, something ageless is shuffling towards you to finish you off.

These stories never quite go away. Earlier this year, the tabloids got excited that the filming of the new series of Downton Abbey was being vexed by spooky occurrences. Downton is filmed at Highclere Castle, the ancestral home of the Carnarvons, complete with its own Tutankhamen museum. That model of rational thought, the actress Shirley MacLaine, had claimed there were nasty supernatural forces swirling around the set.

Explanations of the circulation of mummy curse stories become required when you realise that Egyptologists have found very little evidence for their actual existence in Ancient Egyptian culture. Salima Ikram and Aidan Dodson, for instance, swat curse stories away in a mere two paragraphs in their monumental book The Mummy in Ancient Egypt. Curses are not written in legends on tomb walls, ever. The scribes who composed “threat formulae” (as researchers call them) did so in complex patterns of praise and blame. The idea of an indifferent vengeance launched at all transgressors is a complete fantasy, a later cultural imposition.

Most professional Egyptologists note that the Egyptians longed only for their name to be remembered. This was why new kings built vast monuments in their own name, but also took revenge by smashing out the names of superseded pharaohs or enemies. Why, then, would the archaeologist involved in the patient act of recovering lost kings be cursed? Surely, the old gods would bless them. Anyway, as a jokey British Medical Journal longitudinal survey of the death rates of Egyptologists concluded, there are no apparent statistical anomalies in life expectancy in the profession.

Yet these kinds of explanation do nothing to dispel the circulation of rumours. To rail against superstition or to adopt a corrective attitude that proper science will prevail over false belief obstructs an understanding of the kind of cultural work that magical thinking about curses still performs.

As a cultural historian, I became interested in tracing back the prevalence of curse stories and was rather struck to discover how late in the British encounter with Egypt they seemed to appear. There was a rush of Egyptomania after Napoleon’s invasion in 1798. It reached Britain when the price of Napoleon’s defeat to the English navy was the transfer of all the Egyptian artefacts they had gathered to British ownership – including the famous Rosetta Stone, the key to translating hieroglyphic script. There was no sense of dread here, only sublime awe at the astonishing sophistication of ancient culture.

In 1821, a reconstruction in Piccadilly of Seti I’s tomb was a sensation, visited by thousands without a sense of fear. It started a craze for “mummy unwrapping”, society events where eminent surgeons would publicly unravel mummy bandages, and chisel away at the bitumen preservative in which ancient bodies were preserved, for hours on end in front of fascinated audiences. Thomas “Mummy” Pettigrew, the surgeon who unwrapped over thirty Ancient Egyptian mummies in London, was not considered an unlucky man.

The first Gothic or supernatural fictions about mummy curses appear first in the 1860s, but the satirical use of the awakened mummy to lambast contemporary society (as in Edgar Allan Poe’s “Some Words with a Mummy”) and romances with alluring and exotic ancient princesses long predominated. These turned properly nasty in the 1890s. Arthur Conan Doyle, who hated Egypt as a backward and corrupting place, thought up the first mummy animated to conduct the vengeful will of a modern black magician in his short story “Lot No. 249” in 1894. Richard Marsh published The Beetle in 1897, an extraordinary vision of London struck by a Biblical plague spread by ageless and vengeful Ancient Egyptian priests. Bram Stoker’s Jewel of Seven Stars (1903) used recently discovered radium to suggest that an experiment to use Ancient Egyptian magic to reanimate a woman pharaoh might possibly result in nuclear annihilation.

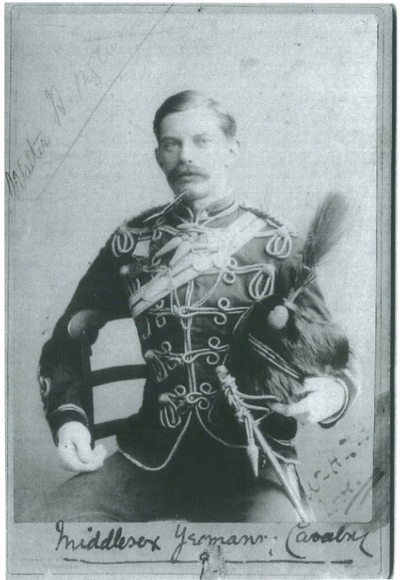

But I have mainly become interested in the life stories of two Victorian gentlemen adventurers, whose stories of being cursed by what they brought home were well known long before Tutmania began.

Douglas Murray was a society gentleman who knew diplomats, colonialists, painters and writers. He was a friend of the rival Egyptologists Ernest Wallis Budge and William Flinders Petrie. He was also a member of the private “Ghost Club”, a group of ardent spiritualists. It was this combination of social contacts, Egyptology and supernatural belief that ensured the story of his curse spread.

What these histories reveal, once they are disentangled from rumour, are narratives of violent colonial encounter with Africa at the moment England begins serious territorial expansion in the 1880s. Douglas Murray wrote an adoring biography of Sir Samuel Baker, the man who followed the White Nile to its source, annexing territory as he went. His brother, Colonel Wyndham Murray, was in the army that occupied Egypt in 1882. Walter Ingram not only fought the dervishes of Sudan but was also involved in the final destruction of the Zulus, fighting at Ulundi in 1879.

The curses of these men are a register in supernatural terms of the knowledge that violence begets violence. I don’t think the curse of the mummy was ever really about Ancient Egypt or the superstitions of North African populations. It was a fantasy that was the product of colonial occupation. That mummy curses remain popular still tells us much about Western fears of the fate of the Middle East.

The curses of these men are a register in supernatural terms of the knowledge that violence begets violence. I don’t think the curse of the mummy was ever really about Ancient Egypt or the superstitions of North African populations. It was a fantasy that was the product of colonial occupation. That mummy curses remain popular still tells us much about Western fears of the fate of the Middle East.

Roger Luckhurst teaches literature at Birkbeck College, University of London. The Mummy’s Curse: The True History of a Dark Fantasy is published by Oxford University Press in October 2012