This article is a preview from the Summer 2016 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

I forgot my PIN number again last Boxing Day. As a small queue formed behind me at the ATM, I stood staring at the keypad, waiting for my brain to click into gear and come up with the magic digits. Did it begin with a five or a six? Suddenly, a number flashed across my consciousness: 6-1-2-2. It seemed to have a sort of resonance. But wasn’t it the PIN for my Sky TV? Or the Barbican booking office? Or even my Apple ID?

People behind me began to break ranks. There was some barely disguised muttering. To hell with it, I thought, and pressed 6-1-2-2. The machine gave a couple of short embarrassed coughs and then brusquely informed me that I was electronically unrecognisable. Only when I reached home and checked the ever-expanding list of PIN codes and security numbers in the back of my diary did I realise that what I had dialled into the machine had not been an ATM code at all. It had been the ancient telephone number of an actor from Scarborough called Derek who had once, after a rather drunken evening in the Hole in the Wall, invited me to join him in his bed at the Crown Hotel.

Now, I would be only too happy to regard this incident as nothing more than an everyday story of encroaching senility. When you’ve reached that stage in your life where your legs have lost the ability to climb much higher than the top deck of a 243, you can hardly expect that local part of the brain devoted to PIN numbers to be in full working order.

But in the past month I’ve been forced to recognise that I’m not so much suffering from occasional lapses of memory as from a mental infirmity that can only be described as perverse amnesia. My brain doesn’t simply forget names and numbers and faces, it makes inappropriate substitutions. That Scarborough telephone number incident was merely one instance of a wholly new syndrome.

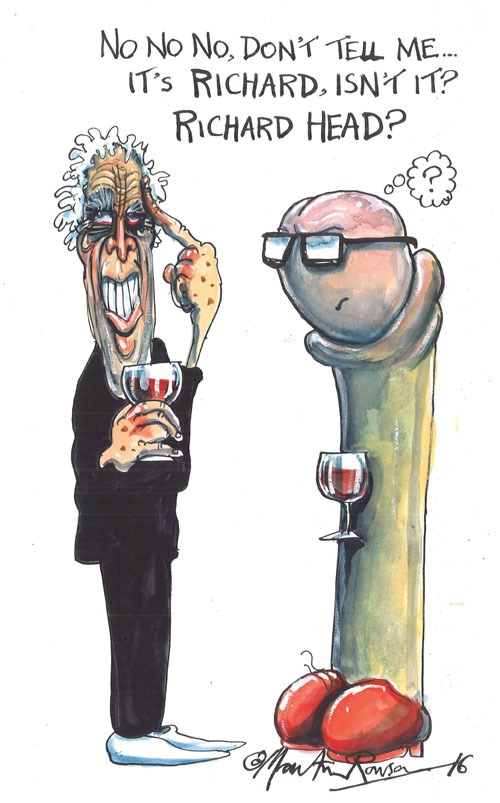

Consider the case of Juliet. We’d not met for the best part of five years when we ran into each other in the Coach and Horses. As soon as she came up to me and smiled, I recognised her immediately. “Janet,” I exclaimed. “Janet! Great to see you. How are things going?”

Things, it quickly turned out, were not going well at all. “I’m Juliet,” she said. “Janet was the person who ran off five years ago with my beloved partner.”

All the way home, I remonstrated with my cortex. Forgetting was fine, I told it, but perverse remembering was a different kettle of fish. What, for example, had my brain to say about that almost disastrous dinner table moment last year when I encouraged my present partner to join me in some sensitive and fulsome memories of a visit to Venice; a visit, she reminded me later, I’d actually undertaken with a former wife? Why hadn’t she pointed this out at the time?

“I didn’t want to draw public attention to your crass emotional infidelity,” she told me with an aggressive tug on the duvet.

My ageing but still virile friend Dennis reckoned there was only one person who could properly interpret my dilemma: Dr Freud. In normal circumstances, Dennis told me over a jalfrezi in the Gopal, we successfully repress all such perverse associations. “They remain latent,” he explained. “But in your case, it seems the censor has relaxed its grip. You’re suffering from memory gain, from uninhibited memory recall. You don’t so much make Freudian slips as set off Freudian landslides. If I was your therapist, I’d be delighted with you. In two shakes of a lamb’s tail I’d have unravelled your Oedipus complex.”

How, I asked, could I put this censor back in place?

Dennis cut to the point. “Frankly, you will have to learn to hold your peace. Don’t speak in company unless you’re spoken to. And use your age to your advantage. If you’re asked a question, mention your failing memory. Claim to have some early signs of frontal temporal dementia. There. Write it down on the napkin.”

I did as I was told. “Anything else?” I said, ballpoint still in hand.

“You might slightly amend what you’ve already written.”

“Amend?”

“Yes, amend. So that my name no longer looks as though it’s spelled with an initial ‘P’.”