If anyone was surprised, it would have been at the voting system. Ninety per cent of bishops in favour; 77 per cent of the clergy; 64 per cent of the laity. That’s 72 per cent overall in favour. For a majority like this, governments would, and do, kill.

For the Church of England, though, a majority like this means: no can do. Sorry, girls, but off you go. Cut along now. God’s own glass ceiling.

The bad news: the Church looks idiotic. The worse news: the Church has either forfeited its claim to godliness or has made God look idiotic.

The two-thirds majority needed in each group was screwed by two-and-a-half lay votes, whisked away in a fudge between the literalist pick-’n’-mixers of the evangelical wing and the Anglo-Catholics who love the aesthetic frills of the old Roman Rite but lack the stomach for its autocracy and the scary logic of its theology.

It wasn’t even a consistent fudge. The Anglo-Catholics’ beef seems to have been with the idea of apostolic succession, bestowed by their man Yosser bar-Yussuf, known as The Anointed, upon Shimon ben-Yonah, now known as St Peter, as in Rome, as in “First Pope”. The evangelical Taliban, who don’t give a toss about apostolic succession, got themselves in a twizzle about 1 Timothy (written by someone who almost certainly wasn’t St Paul), in which the author says: “Let the woman learne in silence with all subiection: But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to vsurpe authoritie ouer the man, but to be in silence.”

After the vote, it was pointed out that Jesus (or, more relevantly, St Peter) was not only a man but a Jew. Nobody was rude enough to mention the fact that the Archbishop of York, who read out the results, was a DARKIE, almost as bad as a woman since, as any fule kno, DARKIES are made out of MUD and have NO SOULS. Everyone was quoting Larkin’s “Church Going” (though most missed the titular pun) after the vote, but they quoted the wrong bit. The lines that strike me sharpest are:

I wonder who

Will be the last, the very last, to seek

This place for what it was

And look. Almost sixty years later, and it still goes on. In the last fifty years, the Church of England has suffered – no, brought on – a 75 per cent shrivelling in professed members. That’s two-thirds gone in just one-twelfth of the church’s lifespan.

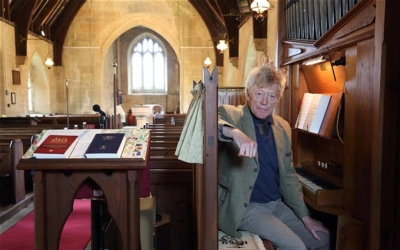

I watched it from the choirstalls and, later, the organ-loft from the age of six. When I was fifteen I became a titulaire and choirmaster in my own right, and simultaneously the awful pale-blue booklets came in. “Series II” they were called, and marked the beginning of the end of Cranmer and King James, Merbecke and Byrd and Gibbons and The Cathedral Psalter: a source of as much remembered beauty – and wistful regret that such beauty is no longer woven, in however secular a fashion, into my life – as any girl from the days when my past was still my future.

So I’m broadly in sympathy with Roger Scruton’s new book Our Church. He subtitles it “A Personal History of the Church of England” and on a wider scale it’s part of his continuing grand project, the Englishing of Scruton, which is odd because he’s already English. He’s just trying to become a different English. It’s a sort of Heideggerian Dasein, a becoming, starting with fox-hunting, and conducted out loud.

As the ecclesiastical backdrop to his project, Scruton’s blue remembered Church of England is entirely plausible.

But as a description of a church that ever was or could be, world with or without end, it isn’t. It’s bits of one, a salmagundi assembled to his taste: Cranmer and Lancelot Andrewes, all those curates in Barbara Pym, Wodehouse, E F Benson and Trollope, the high camp Ritualism of Percy Dearmer, the English Hymnal and the damp-wool gloaming of Thomas Hardy. The Church of England, really, as envisioned by Japanese tourists who’ve been on the internet.

Even the music he yearns for (and sometimes plays, as organist of his village church, behind the curtain at his tiny three-stop instrument) seems more fitted to the grand project than to Scruton the musical aesthetician. His own stuff – his Three Rilke Songs, for example – is reminiscent of the adorable Lili Boulanger, sister of the far nastier Nadia; and it’s hard for a man to dissemble or fool himself in composition (although one of his heroes in The Aesthetics of Music, the anti-semitic flogger/ee Percy Grainger with his nasty-trousered rustic oompah tripe, got as near to it as possible).

But Scruton’s is the Church not of England but of Almost-Was, of Erewhon. It may be crucial to his grand Dasein but it’s not the thing I remember, which predisposes me to dislike the inclusivity implied in the title. Yes, Scruton’s church is better than the Church’s church, even just as a deep repository of that culture which Peter Ackroyd called the “English Music”, but calling it “Our Church” is too much like George Osborne’s “We’re all in it together”, an old rhetorical stunt which he nicked from Thucydides (and indeed Hitler). Well; we’re not all in it together. Our Church my arse.