Medvedenko was speaking. And he was definitely speaking to Masha. But what exactly was he saying?

“Who would want to marry a man with such a large family and such a low blur blur.”

Such a low what? Did he say “salary”?

“Less than blur thousand a month before tax. Who could love me in this blur.”

How many thousand exactly before tax? Did he say “two”? And love me in this what? Love me in this way? Love me in this condition? Love me tender? Love me true?

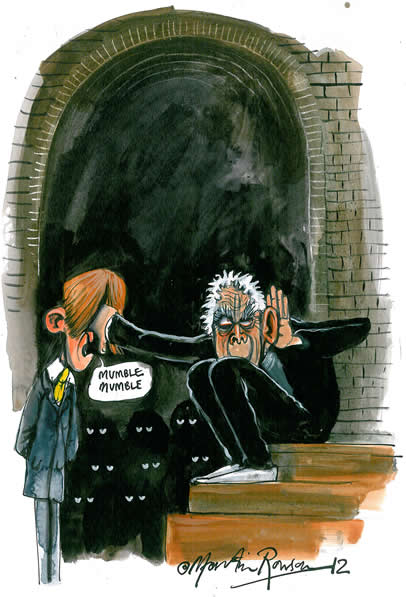

I really couldn’t go on like this, missing every tenth word of the script, especially when several critics had raved about the excellence of Anya Reiss’s new version of The Seagull. But there seemed nothing I could do to improve matters. If I leant any further forward on my third-row bench seat in the Southwark Playhouse in order to hear what was happening in Act One I could easily topple forward into the action.

But perhaps relief was on the way. It was Konstantin’s turn to speak. Come on, Konstantin. Let’s hear you.

“If we start at exactly blur blur we’ll have the moon rising behind blur.”

The moon rising behind what? I had to face facts. My initial theory was that there were just one or two actors under-projecting but as Act One slowly developed I realised I was unable to hear more than nine-tenths of what any one of them was saying. Neither Konstantin nor Masha nor Medvenko nor Trigorin.

It was round about this moment of realisation when the woman squashed up next to me on the bench tapped me on the knee and whispered, “I think we’re in the wrong place.” Even though it was some time since I’d last visited a fringe theatre I could remember how much they liked to involve the audience in the action and assumed for a moment that this was part of the ongoing drama. “I think we’re in the wrong place” had just the right Chekhovian note to it. I was working on a suitably enigmatic response – “Aren’t we all somehow in the wrong place?” – when she and her companion suddenly stood up and shuffled along the bench towards the exit, only pausing briefly when they became seriously entangled up with the actor playing Nina, who was confusingly making her entrance from the exit door of the theatre.

Their departure made my own impossible. It would have seemed like an organised protest. I had to stay and try harder. Now what exactly is Nina saying about her feelings for Tregorin?

“I love his books. They’re so blur blur blur, so so blur.”

I glanced along my crowded bench. No one else seemed to be leaning forward. Was it only my problem? Had there been a sudden deterioration in my hearing since earlier in the year when an audiologist had told me reassuringly that I could hear perfectly well for someone my age and that unless I wanted to hear every word that was being said in a crowded room I could go on living perfectly well for years without the aid of a whistling earpiece?

Of course matters weren’t helped by the theatre being housed beneath London Bridge station so that even the most inconsequential remark on stage was given added resonance and added inaudibility by the rumbling departure of the 20.15 to Tunbridge. But this would have counted for little if only the actors (many of them highly praised in the reviews) had decided to speak with the sort of voice projection that was supposed to set them apart from normal speakers. It was as though the extreme non-theatricality of the setting, the makeshift set, the entrances and exits shared with members of the audience, the basic lighting and the lack of anything resembling a conventional stage had somehow prompted these actors to forget their craft and lapse into the type of muted conversational tone that might have been appropriate in the confines of a confessional box. And they caught it from each other. New characters who arrived on stage with vocal aplomb were quickly drawn into the muttered ambience.

In the interval I checked with others. “Enjoying it?” I said to the woman at my table. “What I can hear,” she said brightly, as though inaudibility was a natural expectation in this theatre and certainly not something worthy of complaint.

I stayed to the end. I wanted to like what I was seeing but not hearing. And there was some modest pleasure to be obtained from the shifting moods of the characters on stage, even if the reasons for the mood shifts had to be more guessed than comprehended. It was, I thought, probably silly of me to take up fringe theatre at such an advanced age. Experimental theatre was for the young, for those in full possession of all their senses. Oldies like me should stick to the West End, where they had handrails and hearing loops and opera glasses and wheelchairs and nurses in attendance.

“Did you enjoy it?” I said to the young leather-jacketed man who walked out of the theatre alongside me after the stuffed seagull had finally been laid to rest at the end of Act Four. “Pardon?” he said with studied politeness.