In Jharia, in the Indian state of Jharkhand, around 600,000 people live on top of one of Asia’s largest deposits of coal. Many of them scratch a meagre living mining the coal which will go to power metropolises like Delhi, Bangalore and Mumbai, and enrich the shareholders of the companies that own the mine. The coal has poisoned this once richly wooded area, the soil, the water and the air are now contaminated. A coal fire has burned under the entire region for more than a century

The fate of Jharia encapsulates the story of how corporate greed, vested interests and the thirst for power can ensure that one of India’s richest areas, in terms of mineral wealth, can remain one of its most economically backward.

In 1971 the Indian coal mines were nationalised. Since then, their operator has been Bharat Coking Coal Limited (BCCL). In Jharia the BCCL conducts mainly opencast mining, which yields better returns than deep mining, though the environmental costs are far higher. Reports suggest that up to 97 per cent of the mining in Jharia is actually illegal since no licences have been issued for the work. Here coal is mined in the villages, next to the houses, on the streets, on railway lines, in the station itself (which is not a station any more). People literally mine on their own doorsteps.

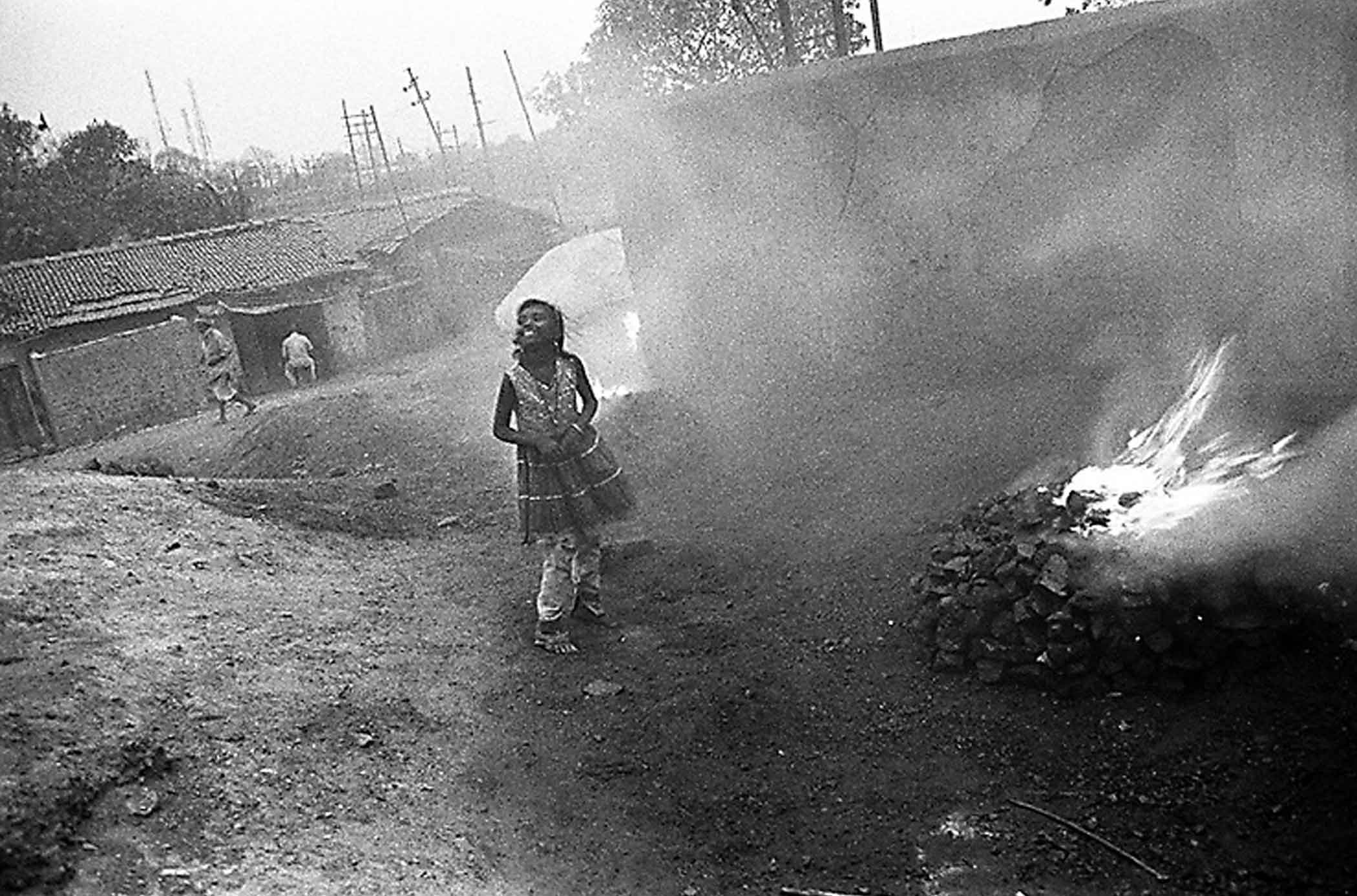

Conventionally after open cast mining, areas are refilled with sand and water so as to encourage re-cultivation and prevent accidents. This has never happened in Jharia, so exposed coal seams still come into contact with oxygen and ignite. According to BCCL estimates there are currently 67 fires burning above ground, and a huge subterranean fire which never goes out.

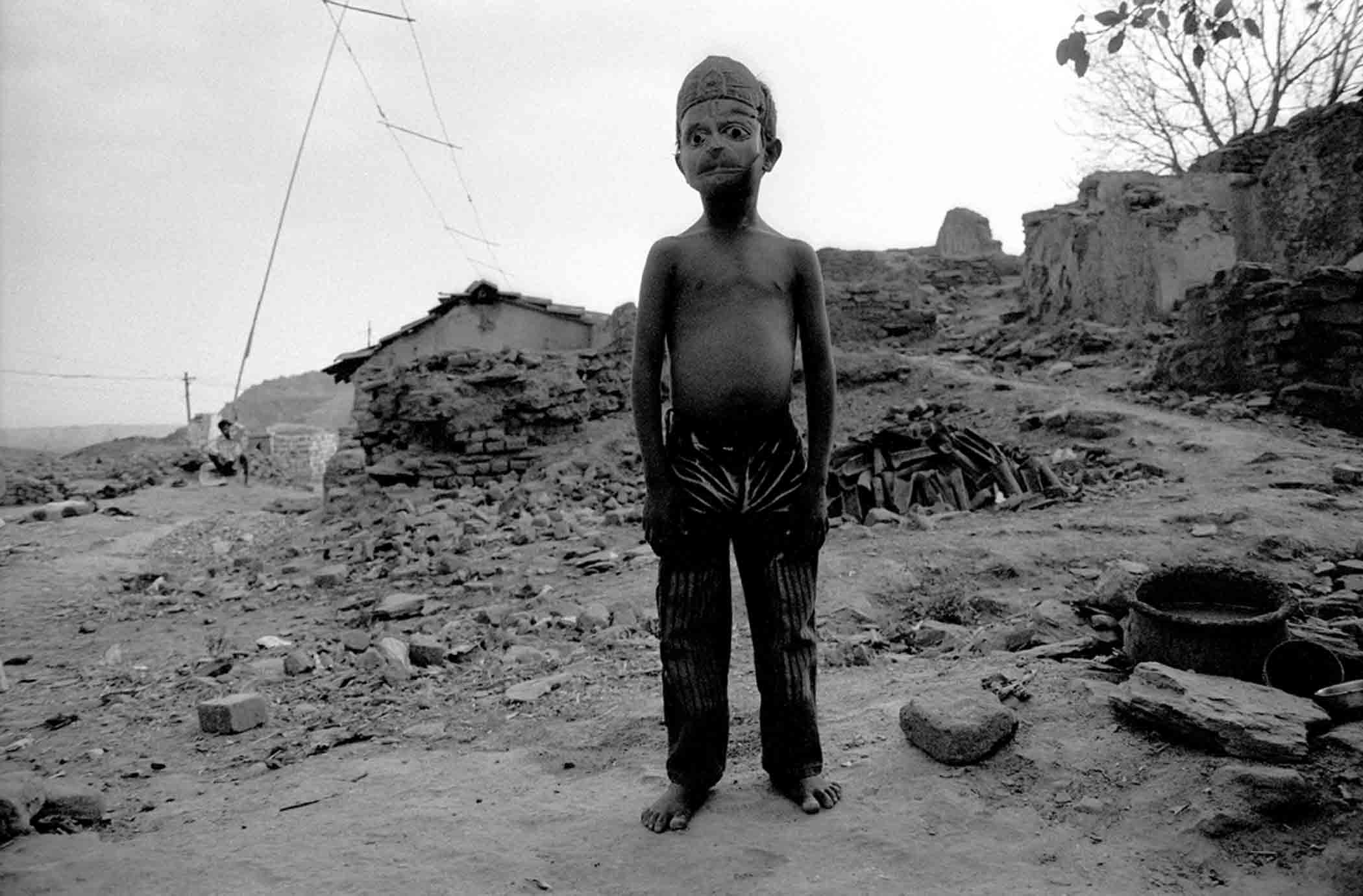

These mining areas are densely populated. Forty per cent of the region’s inhabitants live in the burning, fire-spewing countryside. The ground is subsiding, houses are collapsing. The smoke and vapours contain poisons, among them carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, but also soot, methane and arsenic. The damage to health is enormous. Lung and skin diseases, cancer and stomach disorders beset the population.

Though the BCCL claim there is nothing they can do, the fires could be extinguished with the application of water, clay and sand. But nothing happens. There is no political will to tackle the blazes. Rather, it is in the BCCL’s interest that even more land catches fire – and thus becomes uninhabitable. BCCL needs more land on which coal can be mined in order to achieve the extracted quantities budgeted for the coming business years. And underneath Jharia, and the 600,000 people, lies more than 1,000 million tons of coal.

Instead of dousing the flames, the BCCL and the local authorities are planning one of the world’s biggest resettlements. According to the Jharia Action Plan (JAP) the inhabitants of the areas on fire are supposed to be resettled in Belgaria, a new town in the middle of the jungle. But Belgaria has no school, no medical care, no shops and, worst of all, no jobs. Unsurprisingly many decide to stay in Jharia. On the fire. In spite of the blazes. In spite of the perpetual grey veil that lies over the town. In spite of the air pollution, which makes breathing almost impossible on a bad day. And in spite of the coal dust, which settles like a second skin on the body.

This piece is from the July/August 2013 issue of New Humanist.Subscribe