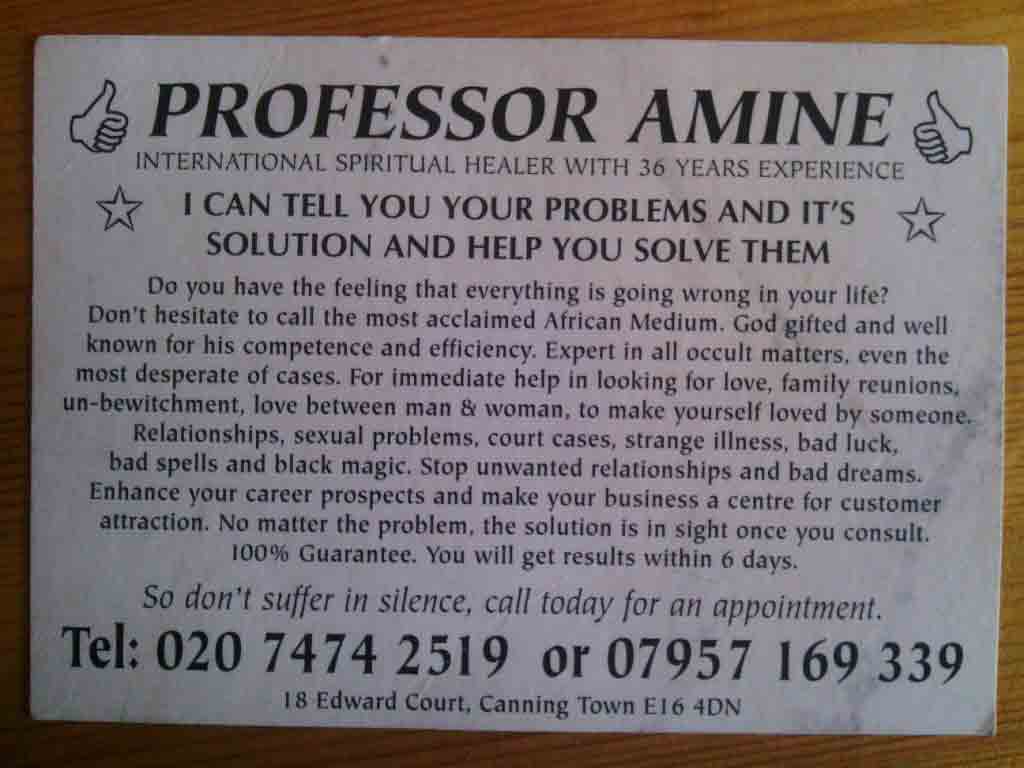

The phrase “bogus faith healer” probably strikes you as something of a tautology, but let's put such quibbles aside for one moment. Coventry's trading standards officers are so concerned about a spate of leaflets and small ads promising to cure bad luck, depression or physical illness through prayer or spells – in return for hefty cash payments, of course - that they have issued an official alert. The statement warns local residents not to “throw their hard earned money or savings after bogus miracle cures that do not yield any results”.

The phrase “bogus faith healer” probably strikes you as something of a tautology, but let's put such quibbles aside for one moment. Coventry's trading standards officers are so concerned about a spate of leaflets and small ads promising to cure bad luck, depression or physical illness through prayer or spells – in return for hefty cash payments, of course - that they have issued an official alert. The statement warns local residents not to “throw their hard earned money or savings after bogus miracle cures that do not yield any results”.

Council staff say the problem is particularly acute within minority religious and ethnic communities, whose members are less likely to seek social support or professional help for their problems. Aware of this vulnerability, healers deliberately target places of worship such as gurdwaras and mosques.

The process is frequently described as a form of grooming: the healer will befriend their victim – often after finding out how much spare cash they are likely to have – and gradually gain their confidence. As the victim's trust increases, so do the healer's payment demands. "Usually it's vulnerable people, people that are at a low in their life and don't know what else to do, where else to turn,” Debbie Morgan, Consumer Protection Officer with Coventry Trading Standards, tells me. “They often just want somebody to talk to."

And the same perceived stigma which leads them to seek the services of a private healer often prevents them coming forward when they finally realise they are being duped. But even when victims do find the strength to report their extorters, the chances of prosecution are slim. Consumer law is designed to deal with faulty washing machines and cowboy builders, not clairvoyants or witch doctors – trading standards officers often feel their hands are tied. "It's very difficult to investigate," says Morgan. "We all know what's going on but you have this fight between what we know is morally wrong and what we can legally prove."

Earlier this month, for example, Sandwell's trading standards team visited a healer who claimed to be able to remove “kala jadoo”, or Islamic black magic. Despite coercing tens of thousands of pounds from one woman and family – including by telling her she would die if she didn't pay up – the healer was given a warning and told to remove misleading advertising. (The same team had greater success in 2010, however, when they successfully prosecuted another healer on fraud and deception charges.)

Trading standards aren't the only ones to be concerned. Last year, the Royal College of Psychiatrists published a leaflet aimed at religious Muslims experiencing mental health issues. Psychiatrists had noticed that presentation of psychological symptoms to GPs was much later within certain Muslim communities than the general population. They realised that signs of serious disorders – including schizophrenia – were being mistaken for Jinn possession or “evil eye”, with sufferers visiting exorcists instead of medical professionals.

The prevalence of exploitative healers is a complex and persistent problem touching on a whole range of social problems; it's not going to be solved easily, especially with the law as it stands. But we can all make life a little bit more difficult for the scammers: next time you see a classified ad or flyer promising financial success or a miracle cure, why not give trading standards a call?