MPs finally voted on 19th December by 366 to 174 to extend the 1990 Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act to allow research on early embryos for the purpose of finding cures for degenerative diseases. The House of Lords followed suit on the 19th January, again after predictions of victory from Cardinal Winning and Lord David Alton. When the 1990 Act was passed research was only permitted on early (up to 14 days) embryos which were spare from fertility treatment in order to investigate infertility miscarriage, contraception, genetic disease and congenital disorders. The prospect of developing stem cells for regenerative therapies and the science involved in 'therapeutic cloning' was not considered when the 1990 HFE Act was discussed.

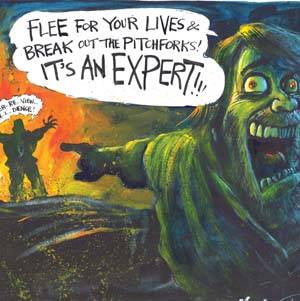

The "pro-life" lobby was extremely well organised and tried to focus the debate back onto the issues that were discussed at length, and resolved by Parliament, in 1990. As a ring-leader of the "pro-embryo research lobby" I received in excess of eighty letters from anti-abortion electors, 20 briefings from "antis" groups, a one thousand name petition from the Oxford University Pro-Life Group, and prayers were said for me by religious constituents and perhaps even by my election agent!

The issue was not, however, a straightforward battle between the religious and the secular. The orthodox Catholic position that full human rights begin when the soul enters at conception is not shared by all Christians, nor of course by Catholicism until the 19th century. As the Bishop of Oxford has pointed out, 70% of all fertilised eggs do not make it to implantation in the womb, and it would be a very inefficient God who would allow heaven to be predominantly inhabited by the souls of pre-implantation embryos. In the House of Commons, we (including Anglicans like Robert Key MP and Ben Bradshaw MP) managed successfully to publicise the views of religious groups who were not opposed to the embryo-work.

One of the most powerful arguments deployed by those opposed to the regulations was that embryo work was unnecessary because adult stem cells could be used. This is untrue but complicated by the fact that it is the aim of embryo researchers to find a way of using adult stem cells and use those in the future instead of the difficult to get hold of embryos and eggs. This argument had to be dealt with by pointing out that; a) those opposed to embryo research still would be even if adult stem cells turned out to be a blind alley,; b) that the regulations only allowed embryos to be used if there was no adult stem cell alternative; and c) that adult stem cell researchers themselves who had most to gain in grants and endowments from concentrating solely on their approach rejected the claim made by pro-lifers on their behalf.

The religious and "pro-life" groups added to their usual "sanctity of life beginning with conception" and "there is an alternative" arguments. This centred around cell nuclear replacment or CNR, and the potential for human cloning. CNR involves transplanting a cell nucleus generated from immune compatible adult cells into an egg whose nucleus has been removed. Although the process of CNR for therapeutic purposes would only involve the generation of embryos up to about 10 days old and there was no prospect of implantation and a pregnancy, the campaigners deliberately fudged this point and talked not about reproductive cloning (as opposed to therapeutic cloning) but about "cloning of human beings".

Rather uniquely, in the campaign against CNR the pro-lifers were joined by unusual bed-fellows some green groups who are against anything genetic (sounds like genetic modification!) or anything engineered (sounds like genetic engineering); but who are passionately in favour of abortion rights. The fact that the Act was passed so convincingly in both Houses suggests two important developments: Firstly, the votes were a rejection by the majority of parliamentarians of the religious and conservative elements that opposed these regulations so vocally. Secondly the majorities were a clear rejection of the rarely expressed but apparently widespread "anti-science" feeling that exists in some parts of the public and media. Indeed, Britain has placed itself firmly at the vanguard of scientific research and we might look back and say it was here that the fightback against anti-science truly began.