This article is from the Spring 2014 issue of New Humanist magazine. You can subscribe here.

There is a passage in Marilynne Robinson’s novel Gilead in which the main character John Ames, a pastor, is walking to his church, and comes across a young couple ahead of him in the street:

The sun had come up brilliantly after a heavy rain, and the trees were glistening and very wet. On some impulse, plain exuberance, I suppose, the fellow jumped up and caught hold of a branch, and a storm of luminous water came pouring down on the two of them, and they laughed and took off running, the girl sweeping water off her hair and her dress as if she were a little bit disgusted, but she wasn’t. It was a beautiful thing to see, like something from a myth. I don’t know why I thought of that now, except perhaps because it is easy to believe in such moments that water was made primarily for blessing, and only secondarily for growing vegetables or doing the wash. I wish I had paid more attention to it.

It is a wonderful, luminous passage, typical of Robinson’s ability to discover the poetic even in the most mundane. Robinson is a Christian – indeed a Calvinist – whose writing is suffused with religious faith. Her fiction has “a Protestant bareness”, as the critic James Wood has put it, that recalls both the English poet George Herbert and “the American religious spirit that produced Congregationalism and 19th-century Transcendentalism and those bareback religious riders Emerson, Thoreau and Melville”.

There is in Robinson’s writing a spiritual force that clearly springs from her religious faith. It is nevertheless a spiritual force that transcends the merely religious. “There is a grandeur in this vision of life,” Darwin wrote in The Origin of Species, expressing his awe at nature’s creation of “endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful”. The springs of Robinson’s awe are different from Darwin’s. And yet she too finds grandeur in all that she touches, whether in the simple details of everyday life or in the great moral dilemmas of human existence. Robinson would probably describe it as the uncovering of a divine presence in the world. But it is also the uncovering of something very human, a celebration of our ability to find the poetic and the transcendent, not through invoking the divine, but as a replacement for the divine.

One does not, of course, have to be religious to appreciate religiously inspired art. One can, as a non-believer, listen to Mozart’s Requiem or Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s qawwali, look upon Michelangelo’s Adam or the patterns of the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque in Isfahan in Iran, read Dante’s Divine Comedy or Lao Zi’s Daode Jing, and be drawn into a world of awe and wonder.

Many believers would question whether non-believers can truly comprehend the meaning of religiously inspired art. We can, however, turn this round and ask a different question. What is it that is “sacred” about sacred art? For religious believers, the sacred, whether in art or otherwise, is clearly that which is associated with the holy and the divine. The composer John Tavener, who died at the end of last year, was one of the great modern creators of sacred music. A profoundly religious man – he was a convert to Russian Orthodoxy – Tavener’s faith and sense of the mystic suffused much of his music. Historically, and in the minds of most people today, the sacred in art is, as it was with Tavener, inextricably linked with religious faith.

There is, however, another sense in which we can think about the sacred in art. Not so much as an expression of the divine but, paradoxically perhaps, more an exploration of what it means to be human; what it is to be human not in the here and now, not in our immediacy, nor merely in our physicality, but in a more transcendental sense. It is a sense that is often difficult to capture in a purely propositional form, but one that we seek to grasp through art or music or poetry. Transcendence does not, however, necessarily have to be understood in a religious fashion, solely in relation to some concept of the divine. It is rather a recognition that our humanness is invested not simply in our existence as individuals or as physical beings but also in our collective existence as social beings and in our ability, as social beings, to rise above our individual physical selves and to see ourselves as part of a larger project, to project onto the world, and onto human life, a meaning or purpose that exists only because we as human beings create it.

The capacity to grasp the transcendent in this fashion has transformed through history. In the premodern world it was difficult to conceive of meaning or purpose except in relation to God, or gods, or as aspects of the universe itself (though there were major strands in ancient Greek, Indian and Chinese philosophy that attempted to understand this in a purely human way). Hence, transcendence was inevitably seen in a religious light. But with modernity it became increasingly plausible to imagine purpose and meaning as humanly created. Indeed, as the French philosophe Denis Diderot claimed: “If we banish man, the thinking and contemplating being, from the face of the earth, this moving and sublime spectacle of nature will be nothing more than a sad and mute scene.” It was “the presence of man which makes the existence of beings meaningful”.

Diderot was a leading figure of the Enlightenment. But this new kind of sensibility had begun to infuse Western art and music from well before the 18th century. From the late medieval period on, “sacred” art became increasingly humanised. The German critic Eric Auerbach called Dante, in the title of a famous study, a “poet of the secular world”. Dante’s Divine Comedy, despite its focus on the eternal and immutable features of heaven and hell, is at heart, Auerbach insisted, a very human exploration of this world.

The Divine Comedy, Auerbach observed, was very different from previous explorations of heaven and hell. In these earlier visions, the dead were either immersed “in the semi-existence of the realm of shades, in which the individual personality is destroyed or enfeebled” or else the good and the saved were separated from the wicked and damned “with a crude moralism which resolutely sets at naught all earthly relations of rank”. In Dante’s other world, on the other hand, the souls retain their this-worldly forms and thoughts and desires and sins and virtues. “Their situation in the hereafter,” as Auerbach puts it, “is merely a continuation, intensification, and definitive fixation of their situation on earth, and what is most particular and personal in their character and fate is fully preserved.” The human takes centre stage in the Divine Comedy, in a way that had not happened previously in Christian thought. In this, Dante looks forward to the poets and artists of the Renaissance and beyond, to Michelangelo’s David and Adam, to Botticelli’s Venus, to Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Falstaff.

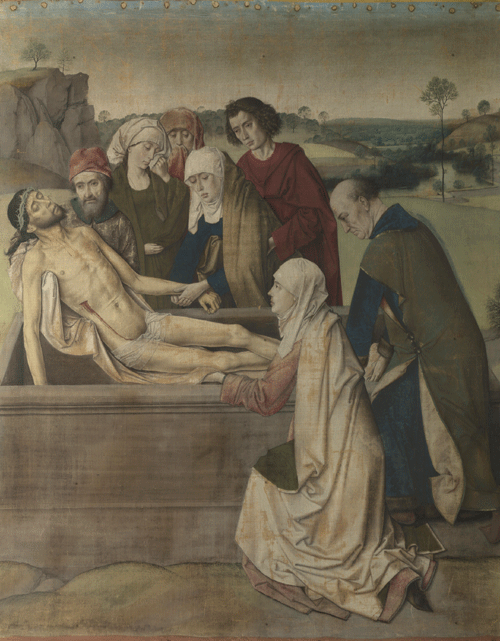

A century after Dante penned the Divine Comedy, the Dutch artist Dieric Bouts painted “The Entombment”. Among the Renaissance masterpieces in London’s National Gallery – the Bellinis, the Botticellis, the Raphaels and da Vincis – Bouts’s work may not stand out. Yet there are few paintings in the gallery as moving, or that tell so well the changing conception of the sacred.

Completed around 1450, and probably designed to be part of an altarpiece, “The Entombment” depicts a traditional theme – the burial of Christ after crucifixion. As he is lowered into the tomb, Christ is held by Joseph of Arimathea, who reverently touches the body through a linen cloth that partly covers it. By Joseph’s side, and behind Christ’s body, stand the three Marys – Mary Salome, Mary of Clopas and the Virgin Mary. Bouts has painted them, one from the front, one from the left and one from the right. One wipes her tears, another covers her mouth, the third, the Virgin Mary, holds Christ’s arm to place it gently in the tomb. She is supported by John, whose haunted face reveals both terror and despair. Nicodemus, a secret admirer of Christ, lowers the feet into the tomb, while the repentant sinner Mary Magdalene looks up into the face of Christ – the only one of the women to raise her eyes.

“The Entombment” reveals not simply the story of Christ’s burial but also the struggle of the artist to bring that story to life. We can see on the canvas the artist’s striving to present both Christ and the mourners not just as placeholders in a particular story but also as real people with whom viewers can find an emotional as well as religious identification. Bouts’s aim is to arouse in his viewers the same emotions of grief, reverence and wonder as those depicted in the painted figures. The mourners are dressed in contemporary clothes and the softened blue and green hues of the painting reflect the sense of sorrow and loss. Joseph, John, Nicodemus and the Marys wear their grief not as symbols but as real pain. Compared to later Renaissance religious painting, the gestures of Bouts’s mourners may seem a little stiff and stylised, the emotions a bit static. Yet it is in this very stiffness that we see Bouts’s struggle to depict both Christ and the mourners as real humans.

The humanising impulse revealed in Dante and Bouts came eventually to transform the character of Western art. Over time, however, the new-found possibilities of detaching the sense of transcendence in art from its religious roots came to be matched by a growing suspicion of the very idea of transcendence. This became particularly true in the post-Enlightenment world. For many, the very rootedness of the idea of transcendence in religious belief made it an uncomfortable concept. The desire to challenge religion became also the desire to challenge the idea of human exceptionalism, and of human experience as in any sense transcendent.

At the same time, there began to develop, too, a much darker view of what it meant to be human, as the optimism about human capacities that had originally suffused the humanist impulse began to ebb away. The late 19th century experienced not simply a crisis of faith – what Nietzsche called “the death of God” – but also what has been called “the crisis of reason”, the beginnings of a set of trends that were to become highly significant in the 20th century: the erosion of Enlightenment optimism, a disenchantment with ideas of progress, a disbelief in concepts of truth. The history of the 20th century – of two world wars, the Depression and Holocaust, Auschwitz and the Gulags, climate change and ethnic cleansing – helped further shatter the old sense of hope and optimism about human capacities.

The 20th century witnessed also a revolution in the way that artists were able to conceive of the human. The emergence of the modernist sensibility, the breakdown of conventional forms of representation, of the old fixed, linear, views of the world, and the growth of a much more fractured, dissonant, abstracted, multilayered, self-conscious awareness transformed the ability of writers and painters and composers to explore the human condition. The result was a growing tension between the new possibilities of art and the darkening perceptions of humans, a tension out of which emerged some astonishing works of art, from Olivier Messiaen’s Quartet at the End of Time to Mark Rothko’s paintings, from Barbara Hepworth’s figures to Pablo Neruda’s odes.

It makes little sense to call such works of art “sacred”. Yet there is a transcendent sensibility that links these to, say, works such as Bach’s Cantatas or Dante’s Divine Comedy. “I’m interested in expressing basic human emotions – tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on,” Mark Rothko once observed. “And the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I can communicate these basic human emotions ... The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience as I had when I painted them.”

What Rothko calls “religious experience” is not what would traditionally be seen as such. It is rather an attempt to grasp the meaning of our humanness not in its immediacy, nor merely in its physicality, but, to borrow a religious term, in a more apophatic sense.

There is, of course, far greater depth and nuance to this story than in the shallow sketch I have given here. It is a sketch primarily about the Western tradition. There is a different story to tell of non-Western traditions. And yet the narrative of the emergence of the humanist impulse and of a non-religious conception of the transcendent has also more universal significance.

Historically, religion has been important in its attempt to give meaning and a dignity to our mundane existence through creating a relationship between the profane and the sacred. It has played a vital role in the development of civilised life because it makes possible the belief that there is more to life than mere animal existence. But the price of transcendence has been enslavement to the sacred. Religion, Leszek Kolakowski, the Polish Marxist-turned-Christian philosopher, acknowledges, “is man’s way of accepting life as inevitable defeat”. To reject the sacred, he adds, “is to reject our own limits”. In this tragic view of the human condition, the sacred exists to protect humanity from the flaws of its own nature: “The sacred order has never ceased, implicitly or explicitly, to proclaim ‘this is how things are, they cannot be otherwise’.”

The sacred, in this sense, is less about the transcendent than it is about the taboo. The sacred sphere, as the French sociologist Emile Durkheim pointed out, constitutes a social space that is set apart and protected from being defiled: a set of rules and practices that cannot be challenged. It protects not the kingdom of heaven but the citadels of earthly power. The sacred, Kolakowski writes, “reaffirms and stabilises the structure of society – its forms and its systems of divisions, and also its injustices, its privileges and its institutionalised instruments of oppression.”

The importance of the humanist impulse is that it helped break the shackles of the sacred while maintaining the sense of the transcendent. Christianity had placed humanity at the centre of the universe, but it was ambiguous about its role there. Humans were fallen creatures, whose very aspirations to knowledge had placed upon them an indelible stain, degrading their moral capacity and willpower, and transforming earthly existence into one of misery and corruption. In Christian theology, the actual centre of the universe is not the earth, but hell.

The new humanist, naturalistic viewpoint that developed from the late Middle Ages dethroned humanity from its privileged position. Copernicus’s heliocentric universe did not merely displace the earth; it seemed to make humanity peripheral too, an insignificant part of the order of things. Yet it also afforded human beings a hitherto unknown dignity. In contrast to the traditional Christian view of humans as fallen creatures, humanists saw people as self-creating agents, free to transform themselves and the world through their actions. Through reason, Descartes wrote, humans possessed free will that “is in itself the noblest thing we can have because it makes us in a certain manner equal to God and exempts us from being his subjects”. It was an extraordinary claim to make for a man as devout as Descartes. But it came to be a sentiment that infused philosophy, politics and culture.

The humanist impulse not only liberated the sense of transcendence from the shackles of the sacred; it also transformed the idea of transcendence. The transcendent was no longer linked to the divine; nor did humans fulfil themselves solely through union with God. Rather humans came to be acknowledged as conscious agents who could transform themselves and the world they inhabited.

It is this sense of humans as realising themselves through, and only through, their own projects that has withered in recent decades. There is both a disillusionment with the prospect of transforming the outer world and a melancholy about the condition of our inner selves. “I’m not interested in things that rise above,” as the American sculptor Mike Kelly, whose “dirty aesthetic” has been highly influential, has put it, “but rather in things that sink below.” This is the non-believing version of the Fall.

If today we are uncomfortable with the idea of the transcendent, if many reject the idea entirely, while others can discover it only in a religious context, it is largely because we have a degraded sense of the human. That is why to read Marilynne Robinson, to gaze upon a Rothko, to listen to Olivier Messiaen can feel so essential. For some it may be to surrender to a religious experience. It is also, paradoxically, to remind ourselves what is truly human about the human condition.