This article is a preview from the Spring 2015 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

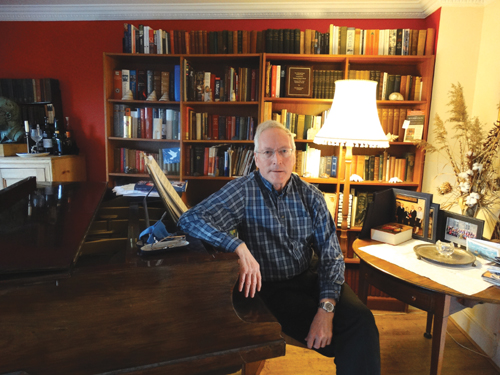

“I think religion has got everything appallingly wrong and it has been terrible for us in sexual terms,” says Diarmaid MacCulloch. Arguably the country’s pre-eminent expert on Christianity, the Professor of the History of the Church at the University of Oxford is shortly to present a BBC2 series about Christianity and its role in shaping our attitudes to sex. In the three-part Sex and the West, MacCulloch posits that Western Christianity has never made up its mind about how it should treat the awkward topic of sex, and that this has led to doomed and ludicrous fights over issues like contraception and equal marriage.

It would be difficult to argue with MacCulloch. Religion ties itself in knots about sex on a daily basis and this interplay is ripe for analysis; in the case of Sex and the West, 150 minutes of analysis on one particular faith. “It is mostly about sex and Christianity,” he admits of the series, saying that punters will be more seduced by “Sex and the West” than they would have been by “Sex and the Church”. “The question lurking behind the series is ‘How Christian are Christian views on sex?’ and therefore did it matter too much when the Church lost control of the situation in the early Enlightenment?”

In his opening monologue, MacCulloch declares sex “a Western obsession”. The West, he says, is set apart from the rest of the world in that it needs to talk constantly about sex. Everyone else just gets on with it and doesn’t really discuss it. “Why I think this is important and not just fun,” he says, “is that it seems to be at the heart of the great culture wars of now: it’s why ISIS and al-Qaeda are so angry. This is the anger of threatened males towards a culture that endlessly offers them sex and sexual possibility.”

Of this series and its relationship to his most recent book, Silence: A Christian History, MacCulloch says that “they spring out of a common interest of mine in the structures of history that make us what we are. I flit around like a butterfly from subject to subject, but it’s the same landscape.” Butterfly maybe, but MacCulloch is considerably more solid in conviction: here is a senior academic, deeply invested in the Church, with no desire to pull punches or offer simpering praise of Church elders. There is something refreshing about MacCulloch’s tendency to puncture pomposity. “He’s not above stirring up trouble,” says Judith Maltby, a colleague of his at Oxford. “His fame has given him a platform to write about contemporary Christianity, and he’s very much taken this on. I would say he’s become quite a prophetic voice for Anglicans.”

Though he calls the word “belief” “a bully-pulpit term used by those who want to make sure that you’re in or out of a particular ideological system”, he regularly attends his local church, St Barnabas in Oxford, and self-identifies as “a candid friend of Christianity”. When I meet him he has just returned from playing the organ at St Barnabas, something he does regularly. “I am immersed in the Church,” he says later.

MacCulloch’s life has in fact been significantly moulded by the two subjects that make up his latest programme. Aware from a young age that he was gay, MacCulloch – a parson’s son – considered this no barrier to entering the clergy. The Church was unsure how to treat his relationship with his boyfriend but ordained him as a deacon nonetheless. He says he thought of his relationship as more or less identical to that of any other clergy marriage, however disconcerting this was for his more conservative colleagues. It was when he was on the verge of being ordained as a priest that things came to a head: the presiding bishop said that he couldn’t go through with it “until the fuss dies down”, in MacCulloch’s words. Refusing to accept that he should have to compromise his sexual relationships for his career in the Church, MacCulloch walked away from his ordination. “What it represented was the Church rejecting me,” he tells me. If today he has any regrets, he hides them totally. For these reasons and more, he says that this series is “extraordinarily personal – it reflects what I want it to say”.

Throughout our conversation, I am reminded of Stephen Fry’s line about the Catholic Church being utterly sex-obsessed: “The only people who are obsessed with food are anorexics and the morbidly obese, and that in erotic terms is the Catholic Church in a nutshell.” From celibacy to abortion, from contraception to homosexuality, people’s private sexual decisions seem to be the domain over which the Church likes to exercise maximum possible control. It was in the 11th century, says MacCulloch, that this micro-management began. What better demonstration of this perverse need is there than the enforcement of celibacy upon its own homosexual clergy? Even now, though gay clergy can be ordained as part of the Church of England, the Church insists not only that they remain unmarried but also that they be celibate. How do senior clerical figures justify this? I ask MacCulloch. “I think they make sense of it because they think that heterosexual sex is the real sex; gay sex is an indulgence, and therefore to commit yourself to the Church means committing yourself to keeping away from this nasty thing.” Though the bishops realise how nonsensical this is, “there’s nothing they can do about it because they’re terrified of noisy Evangelicals who are committed to a narrow literalist reading of the Bible and whom most bishops still see as the only people with any money in the Church. I can tell you this because I’ve had them to lunch and watched it happen.”

MacCulloch believes that the Church’s turmoil over equal marriage is not only a battle they are doomed to lose, but one over which they look increasingly pathetic. “The bishops in their heart of hearts know the game is up. And they are just fighting a stupid rearguard action.” What does it say about those in the Church, I ask, that the rhetoric around equal marriage is fixated on male relationships, with barely a whisper about lesbian partnerships? “It highlights the fact that their priorities are still those of heterosexual men, most leaders among them educated in English public schools,” says MacCulloch. “And those are the people most neurotic about matters sexual. Single-sex public schools produce messed-up people; and messed-up people are the people that lead the Church.” In addition, he says, “Men are not very interested in women, really. They’re interested in women for one thing but they’re not interested in what women think or do.”

Sex and the West is divided into episodes titled “From Pleasure to Sin”, “Sexual Revolution” and “Christianity vs the West”. The last deals with the period from 1700 onwards. MacCulloch believes that, by the time of the Enlightenment, Christianity had lost control of the discourse on sex, a discourse it had dominated since the fourth century. It lost control when sex became more a matter of choice. As he explains in his book A History of Christianity, at the beginning of the 18th century London and Amsterdam experienced a significant change that saw the proliferation of prostitution as well as “cruising grounds” for gay men. This change was effected by both societies banishing famine and affording ordinary people “spending power beyond surviving”. What people did was buy pottery, says MacCulloch. But they also bought sex. “The Church simply could not control that, and it had no discourse for doing so.” As a respected authority on one’s sex life, the Church has not recovered from this position, and for many its edicts are now an irrelevance.

It would be impossible to present a series about religion and sexuality without dwelling on the Catholic Church’s role in rape and child-abuse cases, particularly in the last century, one in which garbled apologism and details of cover-ups have been appallingly common. The programme’s second episode deals with the first child-abuse scandal within the Catholic Church, that of the Piarists in 17th-century Italy. MacCulloch credits the emergence of “systematic child abuse” to two features of the Counter-Reformation: first and perhaps most important was the fact that the Catholic Church effectively enforced universal celibacy on its clergy; second, the Counter-Reformation introduced “social work on a huge scale for the Church”. The result, he explains, was simple: the now celibate clergy were “full of anguish, suddenly deprived of sexual consolation”, and were dealing with a huge influx of young and vulnerable people over whom they wielded authority.

“A lot of bad sex is about power,” MacCulloch explains. “People who are terribly unhappy about sex, moving in an entirely male world, will take it out on those in their care. Anyone uncomfortable about their sexuality may be attracted to an institution where they can exercise power.” It is clear that all-male institutions, private schools and religious orders among them, come in for significant criticism from MacCulloch for being Petri dishes in which damaging sexual attitudes – often “concealed, fearful homosexuality” – can grow. The Church has been in denial about the link between celibacy and child abuse, “but they’re beginning to admit it. So the game’s up. They know it.” The problem isn’t the celibacy per se, says MacCulloch, who thinks the decision to abstain from sexual relations can be a noble practice. The problem is that the celibacy is enforced. “It’s stupid, and it’s something that the Church committed itself to in the 11th century. And it was a big, big, big mistake.”

A number of Church leaders might watch Sex and the West through their fingers. There are teachings and scandals that look increasingly ugly as time passes. But religion cannot shy away from its history, nor ignore the fact that on sexual issues it is currently out of step with the great majority of the public. As MacCulloch notes, if Evangelicals wish to recruit from the under-30s they have no option but to alter their rhetoric, because of how radically the young differ on topics like equal marriage and abortion. How Christianity responds to this kind of disparity in the next few decades will have a great impact on how it is perceived from both inside and outside its congregations.

Diarmaid MacCulloch’s series Sex and the Church begins on BBC2 on Friday 10 April at 9pm. His latest book, Silence: A Christian History, is published by Allen Lane

Photo: Ralph Jones