This article is a preview from the Spring 2015 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

"Recently, photography has become almost as widely practiced an amusement as sex and dancing,” wrote Susan Sontag in On Photography. Nearly four decades on, however, such a statement sounds somewhat conservative. Today, images captured and circulated on cameras, phones and online have become inextricable from “real life” itself. Last year in particular, our understandings – accurate or otherwise – of conflicts worldwide were formed not only through the work of professional photographers but through social media, as images circulated of Islamic State beheadings, destruction in Syria and death in Gaza. But whilst such graphic shots often incite instant horror, they do not always invite reflection, and are a far cry from those considered bodies of work that speak of suffering without always directly showing it.

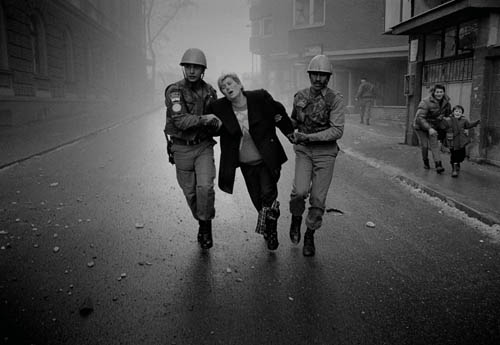

The work on the siege of Sarajevo by award-winning photographer Paul Lowe is a case in point. Last summer in the Bosnian capital, an exhibition featuring the photographer’s images was well attended – testimony not only to the power of the pictures but to the enduring fascination with the most brutal and intimate conflict witnessed in Europe since the Second World War. Tourists and locals stood grounded as they gazed at black and white shots showing showing death and destruction, grief and resilience in the besieged city. Most haunting of all was a close shot of a woman clasping a child with one hand and her despairing face with another. No Instagrammed snap could possibly compete.

Though Lowe has covered many of the landmark events of recent decades – from the fall of the Berlin Wall to famine in Africa, the destruction of Grozny to the release of Nelson Mandela – it’s the Bosnian war that seems most to define him. Over two decades ago, he came to the country to cover its conflict and document Yugoslavia’s dissolution. Today, he divides his time between Sarajevo and London, where he heads the MA in Photojournalism and Documentary Photography at the London College of Communication. Sipping black coffee on a Sarajevo rooftop, he reflected that Bosnia has been “certainly on the personal level, and also probably the professional level, the most important story I’ve done”.

Reacting to my suggestion that the way many journalists rushed to besieged Sarajevo could seem romantic in hindsight, Lowe insists, “There was a very clear moral agenda here, despite the fact there were obviously issues on both sides, that predominantly the burden of aggression fell on the Serbian side and that the people of Sarajevo had a genuine need.” For a long time, however, the narrative from governments contradicted that produced by journalists experiencing the siege first hand. “We were – I say the collective ‘we’ – telling this story that there was a way in which the siege could probably be lifted,” Lowe says, adding that “there [was] very clear right and wrong in this, and that wasn’t necessarily being partisan – although I don’t mind being partisan.” We discuss the distinction between objectivity and neutrality. “To be frank,” Lowe says, “I’m not a big believer in objectivity. It’s a very complex and loaded term that in the end doesn’t really mean anything. You can be ‘neutral’ but still say, ‘This is right and this is wrong’.” After all, he says, that’s how the legal system is meant to work; it’s “supposed to be neutral in its judgment but it still makes judgments – certainly on the international level – about whether something is effectively morally right or morally wrong.”

Lowe is not afraid to turn the flashlight on his own profession. He told me how, in his doctoral thesis submitted last year, he argues that simply “witnessing” is morally distinct from “bearing witness”; the latter, he tells me, is an “active process of testimony” going beyond saying simply, “This is what I saw”. In bearing witness, photographers move past a “passive” presentation of the situation to what Lowe calls a “more accurate process of engagement with it”. A photographer bearing witness, Lowe says, is often providing a “testimony about – and very often on behalf of – someone who can’t provide that testimony”.

But producing such testimony is not without its dilemmas. Sontag described photographing as “essentially an act of non-intervention”, remarking how “plausible” it had become, “in situations where the photographer has the choice between a photograph and a life, to choose the photograph”. So where lies the moment when a photographer should put down their equipment and step in to alleviate suffering? “First of all, I’m not a paramedic,” says Lowe. “The only way you can actually justify you being there is to do what you what you do as a journalist, because if you don’t then you’re just a kind of glorified tourist. So your number-one responsibility, I think, is to document or record or tell the story.” Yet there are moments, he adds, when one’s “duty as a civic human being overrides everything else, and if you can help somebody you should. If you’ve got a car and there’s somebody bleeding to death then obviously you would try and save their life first if possible.” It’s a predicament most photojournalists must face at some point in their careers.

Lowe recalls being in Rwanda to cover the first anniversary of the genocide. He heard of unrest at a Hutu refugee camp of which the Tutsi government wanted to regain control, and headed there with the Australian military. “The Tutsis were trying to move a large group of refugees and they’d corralled them into a relatively small space.” Outside the camp, Lowe and his peers heard what seemed like shots being fired; fellow journalists left for Kigali but Lowe stayed. Helped by a Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) team, he entered to find around 3,000 people crushed to death in a stampede.

“There were a lot of babies,” Lowe remembers, explaining how they had survived when their mothers, carrying the infants on their backs, had fallen to the ground and suffocated. It was a horrendous scene; “a carpet of bodies with babies still attached to them.” To get to the centre where the MSF team was treating the wounded, one had to walk across the mass of bodies. “That was a very tough decision to make,” Lowe says, in a tone entirely devoid of heroism. “I felt it was important to document what was going on so I did that. I took pictures. When I’d finished, then I actually went out and tried to help with bringing these children, these babies, into the medical centre. It was pretty awful because there was a point when I was carrying a baby back and an MSF doctor, said, ‘We can’t take any more children, because we’re full, and if we take any more, the ones we’ve got now will be at risk of dying’.” Lowe had no choice but to leave the baby (who wasn’t injured) with the surviving refugees. The photographer’s description of the experience as “very, very difficult” hardly seems to cover it. “I was the only journalist there, and there was definitely that sense of having a certain moral obligation to bear witness and to get my story out,” Lowe explains.

On the difficulty of making split-second decisions on whether to act, he explains the importance of taking time in advance to consider why are you there. Lowe says it is vital “to be comfortable with the reason why you’re doing what you’re doing.” Whether heading into a conflict or a more mundane situation, one is “in one sense invading the personal space of somebody. There’s a certain moral responsibility to be, as far as you can, authentic and truthful. It’s a very fine line as a journalist. You’re often trying to get just that little bit more than you probably should out of a situation, but not so much that you cause offence or upset or discomfort to the people you’re working with. There’s often that kind of difficult negotiation which in some ways you just have to do by feel, as to whether your presence is still acceptable or whether it’s making the situation worse.”

It’s in big news stories with lots of people, Lowe says, that the question of whether one is helping or being voyeuristic can become especially problematic. If he had a crisis of confidence, it was around that issue, in Kosovo in 1999. Lowe hadn’t covered the Kosovo crisis in great depth so didn’t feel it was “his” story. When refugees started heading over the Kosovo border, Lowe went to cover it. He decided to produce portraits exploring the objects that people take when they have to hurriedly leave their homes. He recalls watching journalists ask weary refugees how they felt. “That made me question, in a big story like that, why am I so arrogant to think that my presence is making a difference when there’s loads of other journalists there as well? What is it I’m bringing that’s unique?” Since then, Lowe has worked more on stories in which the story is less well known or documented.

One would presume that the proliferation of the means of image production and circulation makes it difficult for photographers to find truly undocumented stories, or to shock and inform the viewer. But Lowe sees nothing to fear in the rising ubiquity of the camera, and has faith in the longevity of the professionally produced image in a world of citizen journalism. Only a small handful of the relatively few citizen journalism images received by news outlets make it on to front pages, he says. In terms of the historical record, such images tend to fade rather fast. He gives the example of the London 7/7 bombings in 2005; when it came to the year anniversary, the “vast majority” of pictures used were those taken by professional photographers. Meanwhile, Lowe insists there remains a “huge gulf” between a Facebook snap and a long-term body of documentary work. “The expansion of people taking pictures has made those bodies of work that really are authored and thoughtful and well-crafted and well-made and passionate even more valuable than they were before.” To tell a story and “produce a body of work over a sustained period of time that really transcends the kind of pure recording function of the camera and starts to get into its imaginative and interpretative possibilities is a quantum leap,” he says.

Indeed, Lowe’s words convey a reflexivity and accumulated reasoning that would probably not be found in the back-stories to most snapshots uploaded to social media today. In a world whirring with on-tap pictures of blood and brutality, professionals alert to the responsibility of representation and the dilemmas of documenting suffering are needed more than ever. An onslaught of online images arguably risks brutalising the viewer, but a single image on a front page or in a considered monograph better serves to alert us to brutality and rally against it. The role of the professional photographer is far from redundant.