This article is a preview from the Autumn 2015 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

The Happiness Industry (Verso) by William Davies

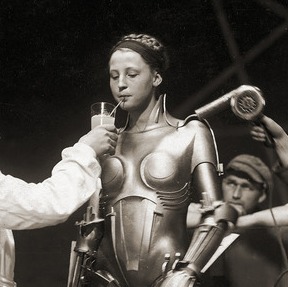

Hudson Yard real estate project in New York City is set to be the most ambitious experiment yet in “quantified community”. Set to cater for 5,000 apartments, offices, retail space and a school, Hudson Yard will be built to enable maximal data-mining of its population. “Treating humans like white rats,” as William Davies puts it, “is now becoming integrated into the principles of urban planning.”

Davies’s new book shows how “managing our happiness” is becoming an increasingly lucrative and insidious industry. True to its subtitle, “How the Government and Big Business Sold Us Well-Being”, it exposes the powerful interests that benefit from our increased willingness to monitor and meddle with our mental states. But Davies takes us much further than this. It is not just that Hudson Yard will soon exist. It is the fact that this Panopticon project is being heralded as “social progress” and – most disturbingly – that people actually want to live there.

The Happiness Industry is the story of how we got here. Davies guides us through a cast of characters who took us forward in this zigzag journey. We start, naturally enough, with the founder of utilitarianism. We know Jeremy Bentham for his principle of “the greatest good for the greatest number”. Davies presents him as a forefather of the happiness industry. His ideas about the state and the free market working to punish and reward, through pleasure and pain, set the stage for “the entangling of psychological research and capitalism” that was to shape twentieth-century business.

The “science of happiness”, then, has been around at least since the Enlightenment. From Wilhelm Wundt, who set up the first psych lab in 1879, through the post war Chicago School of Economics to Frederick Winslow Taylor, the pioneer “management consultant”, Davies’s book shows us that this thinking is nothing new.

Then why are we worrying? Google’s “chief happiness officers”, the opening up of official happiness statistics agencies around the globe: these are simply the latest developments in a trend ongoing since the eighteenth century. Not so fast. Yes, Davies’s book argues that the current science is “simply the latest iteration of an ongoing project which assumes the relationship between mind and world is amenable to mathematical scrutiny”. Yet the tools with which we are able to scrutinise ourselves are sharpening at a scarily exponential rate.

Davies is not a polemicist. He is an academic and a polymath par excellence. Now developing Goldsmiths’ new PPE degree, he has worked at the Centre for Interdisciplinary Methodologies at Warwick and at Oxford’s Institute for Science Innovation and Society. This explains both the mastery of The Happiness Industry and the author’s tendency to fight shy of confronting the horror of his subject head on. Hints at the dystopic run through the book, dished out in parcels of grisly humour and flashes of electric-chair clarity. This is a world where the capitalist imperative to ensure compliant and productive subjects brings our interior life, what makes us human, under an ever-tightening grip. It’s a world where friendships are pursued for the chemical kick and “the only escape from a manager who wants to become your friend is to become physically ill”. As Davies points out, the World Health Organisation has predicted that mental health disorders will have become the world’s largest cause of death and disability by 2020.

In an article for The Atlantic promoting his book, Davies poses the question with clarity: “What if the greatest threat to capitalism, at least in the liberal West, is simply lack of enthusiasm and activity?” If so, we are entering an era of unprecedented levels of social control, merely in order to keep us all “working”. Gallup has estimated that the unhappiness of employees is costing the US economy $500bn a year in productivity, lost tax receipts and health-care costs. Britain has an even greater productivity crisis on its hands, while stress, depression or anxiety accounted for 39 per cent of all work-related illness in 2013-2014. Davies seems to understand the urgency, yet his talk of a “growing unease” feels too casual. “The risk is that science ends up blaming – and medicating – individuals for their own misery and ignores the context that contributed to it,” he warns. With therapists installed in UK Job Centres and the threat of benefits being withdrawn if mental health treatment is refused, isn’t this “risk” already a reality?

The Happiness Industry is a book about biopolitics, packaged as a journalistic exposé. As a critical history of social control, it has more similarities with Foucault’s histories of sexuality and madness than with The Secret World of Fifa or Criminal Capital. That Davies doesn’t position his book in this vein may broaden its appeal outside academia and the left. In one respect, this is a strength. The harnessing of our moods and emotions to the pursuit of economic success should be of prime concern to right-wing libertarians and indeed anyone who places humanity above the interests of the few.

Yet there is a rich seam of anti-capitalist thinking that explores the same core themes: Davies shares a concern with the way in which subjectivity and desire are bound up with the functioning of the capitalist system. He is likewise concerned with “the soul at work” – the effect on employees of having to invest so much of themselves in their labour, discussed by Emma Dowling in the Summer 2015 New Humanist – although he shuns such emotive language.

“Whenever experts seek to witness our shopping habits, our brains or our stress levels,” writes Davies, “they are contributing to the project that Bentham mapped out.” Davies sees this project – founded on the utopian assumption that we can resolve all moral and political questions with the help of a pulse monitor, brain scanner or iPhone 6 Health App – as profoundly mistaken. He has given us a book that traces the origins and permutations of this mistake, and argues that we are falling increasingly in its thrall.

But there is little attempt to sketch a response, let alone a politics of resistance. What if, asks Davies, the tens of billions of dollars spent on the happiness industry were channelled towards “designing and implanting alternative forms of political-economic organisation”? The benefits of deeper democracy, a participative economy and the four-day week are duly extolled. Yet this seems a circular argument. If the deep soil of our society is becoming as barren as this book implies, such seeds will simply not grow.

Davies acknowledges a more fundamental issue, residing in our use of language and communication. He proposes we relearn the lost skill of listening. “In a society organised around objective psychological measurement,” he says, “the power to listen is a potentially iconoclastic one.” Unsurprisingly for a book about social control, the call is for the people to take the power back, asserting their voice and their difference from the silent “white rats” imagined by the quantified community.

But it is not enough to call on the “enlightened” practitioners, experts and managers, as Davies does, to sign up to such a cause. Having worked in research and policy, Davies wants a solution, perhaps, that can be led by researchers and policy makers. There is none. As The Happiness Industry clearly shows, the science of wellbeing is shaped by the socio-political context of the times. It’s a signpost for how our era sees what it is to be human. Davies is ideally placed to show us how we got here. We need different thinkers to posit a way ahead.