Larissa MacFarquhar’s new book, Strangers Drowning, examines the stories of people who live according to extreme ethical commitment. Someone donates their kidney to a stranger; a couple adopts twenty children; another couple founds a leprosy colony. In theory, we honour generosity and high ideals, but there is some scepticism, even hostility, towards “do-gooders”. Why? Here, MacFarquhar discusses some of the main issues raised in her book.

How did you come to the topic of extreme altruists?

I’d been reading moral philosophy on the question of how much morality can demand of us. On the one hand you have Peter Singer and utilitarians saying it can demand almost everything, and on the other you have people like Bernard Williams saying no, if we are servants of the world, then much of what makes life worth living will have to be abandoned – like devotion to family, devotion to work, commitment to art, music. There was a particular essay by the American philosopher Susan Wolf, “Moral Saints”. In it she makes the argument that a morally perfect person would be an unappealing human being who we would not want to be, much less be friends with. I thought that was an incredibly important and interesting argument – because most people would agree with her. She’s probably right about the abstract perfect person. I’m not a philosopher, so this is where I thought I as a journalist could look at the debate, not as an abstract but in the actual lives of people who have committed themselves so wholly to various moral principles that they push it almost as far as it’s possible to go. What do those lives look like? How do we feel about them? Do we think they’ve pushed things too far? Do their lives seem empty or overly rigid or insufficiently devoted to family, or not?

How did you find the people you profile? Were there people you discounted?

They had to be fairly extreme because that’s what I was interested in: what happens if you push moral principles very far. On the other hand, I wanted them to be a genuine challenge. I had only myself as a way to judge that. I excluded anyone that I really disliked or whose ideas I thought were really stupid or bad.

You use the word “do-gooders”, which is pejorative. Did you feel any ambivalence yourself when you started?

No. I didn’t and I still don’t feel any ambivalence towards them. I wholeheartedly admire them. The reason I used the word do-gooder is because I wanted to analyse and articulate what I felt was a suspicion and hostility towards do-gooders. In the process of writing and talking to people I found that if you say there’s an ambivalence towards people who live very moral lives, people say, “no there isn’t”. But if you use the term do-gooder, instantly everyone knows what you’re talking about. They feel it in themselves and they’re moved to examine it: why do I have this hostile? In that term is captured the thing I want to evaluate. I also wanted to rescue the term from that pejorative connotation.

Why are we so ambivalent?

They can make us feel guilty or irritated. Even if they say nothing explicitly, they’re implicitly rebuking us for the way we live our lives. But there’s also this long cultural history of various theories that serve to undermine a moral life. They’re working at us at an unconscious level. I wanted to bring that to consciousness and make people think about this set of beliefs which underlies a lot of feelings about these people and examine them and think: do we really believe this?

Once morality was closely tied to religion. Is it harder to understand non-religious people who choose extreme morality?

We have a much easier time understanding very moral people who are religious. It makes more sense to us. Especially in certain religions – Christianity, Hinduism. Buddhism – we’re used to the idea of a religious person going to an extreme, often an ascetic extreme. For example, Kimberly Brown-Whale, the Methodist preacher [featured in the book]. All the people I met who wanted to donate their kidneys to a stranger encountered enormous confusion and resistance from psychologists and others – except for her. People thought “you’re a religious person, that’s the sort of thing pastors do”. Around half the people in my book are atheists or secular, and it’s they who find themselves having a greater burden of explanation.

Are there major differences between very moral secular and religious people?

One of the questions I touched on in the book was, what difference does religion make to morally driven people? Kimberly suggested something that rang true to several people – she said if you believe in god, you believe that ultimately the world is god’s business and it’s up to him how things are going to turn out, which doesn’t excuse you from responsibility, you still have to work as hard as you can to do good in whatever way seems to you best, but it’s not ultimately up to you. Whereas if you don’t believe in god, there’s an additional layer of both despair and urgency, because you think no, actually, we’re alone here. It’s just us humans and if we don’t fix our world, nobody else is going to.

I don’t think in this tiny and totally unscientific survey of people I’ve written about, that there’s any difference in the degree of commitment or urgency – but I do think on the meta-ethical level there’s a profound difference. Certainly we know from when atheism began to rise in the 19th century, it was a very commonly held thought that in the absence of god or the threat of hell or the promise of heaven, no-one would have any reason to act morally. Not we obviously know that’s not true, but it continues to be striking how little difference religion seems to make.

The altruists in your book are noticeably rational. You use the phrase that they plan their good deeds “in cold blood”.

The effective altruists, utilitarians, are especially cold blooded and rational. I think it’s a difference not so much between secularism and faith, but the sort of person who is haphazard and spontaneous in their good deeds – goes about their life and suddenly sees a poster with a starving child and give money to the charity because they are moved emotionally – and the people I’m writing about. They’re planning a whole life’s commitment and when you do that, you’re not constantly in a state of emotional arousal. You’d go insane. You have to make plans for what you’re going to do in the same ways an ordinary person would make plans for their career. Their moral commitment is their career, so they’re not spontaneous about it.

Why do people often respond to extreme altruists by assuming they are insane?

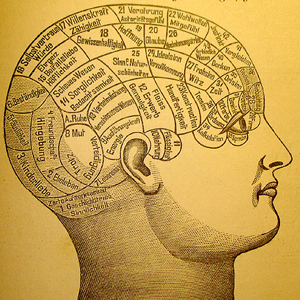

It’s changing actually. There is much more interest in altruism within psychology these days, and more acceptance of the idea that altruism might be a straightforward human characteristic rather than a twisted form of something else. The residual scepticism within psychology comes from psychoanalysis. Freud believed a certain amount of moral feeling was normal but anything too extreme, that got too far away from egotism and self-interest, seemed weird and unhealthy to him. He called it moral masochism. His daughter Anna Freud was even more hostile than he was. She thought it was a perversion, that you would get your satisfaction through somebody else rather than directly. There were lots of lesser known psychoanalysts who shared this sense that it was unnatural, a perverted form of selfishness.

One thing that comes across are the complications of these huge acts of kindness. Is there always an unintended consequence?

Anyone who is committed wholly to living an altruistic life is going to run into conflicts with other things that we value, such as devotion to your family, such as work other than helping other people, such as enjoyment – from art and music to having a glass of wine in the evening or whatever. The extremity of their commitment is what causes these conflicts that ordinary acts of kindness do not bring up. But we could all do a lot more for other people before reaching the point where it seriously conflicted with caring for our own family or causing us to do different work than the work we love.

You mention the historical idea of gift-giving being aggressive if it’s not reciprocal. Does that have political implications?

There are many different critiques of foreign aid. Most are pragmatic critiques: aid doesn’t work or doesn’t work the way it’s intended to. There have been countless examples of aid projects gone wrong, either being ineffective or actually causing harm. But beyond the pragmatic critiques, it’s certainly true that there’s a political problem. It can be perceived as a neo-colonial condescending idea that we’re going to help you because you are poor benighted third world people and we are knowledgeable first world people. Of course that is politically reprehensible. No one likes to be the recipient of charity. It’s difficult to receive big gifts, even from a friend. Kidney donation is even complicated within a family – to owe such a huge debt is difficult. Some people can receive a gift with good grace but many of us don’t like feeling so dependent, so inevitably that dynamic comes in whether it’s a gift within a family, or from one country to another.

Did you’re view of extreme altruists change between the beginning of the project and the end?

My view of the altruists did not change. I admired them at the beginning and I admired them at the end. They’re not saints, they’re human beings. That to me is what’s moving about them. They aren’t always certain what is the right way to act. They do things they regret and things don’t work out the way they had hoped. What changed in the course of writing this book was that I came to have a deeper respect for the forces which push against do-gooders. If everyone were that deeply committed to helping strangers at the expense of the people they love the most, the world would be so different it’s hard for me to even imagine. I’m certain that the world is better for the existence of these people, but I don’t think that resistances to them are merely selfish, guilty or irritable. They engage very deep and honourable human impulses – like the desire to take care of your family at the expense of everyone else – that I wouldn’t want to banish from the world. I realised that the problem of how much morality can demand of you is even harder than I had understood.

What do you think we could learn from those people?

One of the things I think we can learn is that moral commitment does not necessarily commit you to a miserable life of sacrifice and panic. Certainly the people I’ve written about have made sacrifices of every day comfort – and admittedly these are people who don’t really miss the extra pairs of shoes, the dinners out, the kinds of things they have given up. But in exchange they’ve got something that makes them far happier, which is this sense of fulfilled purpose, and a feeling they are living their lives as they ought to, which is an incredible thing.