The image of a patient reclining on a couch has become a cultural shorthand for psychotherapy, seen in cartoons, artwork, and magazines. Although newer forms of therapy eschew the couch, this is the classic arrangement of a psychoanalyst's office, established by Sigmund Freud: the analyst sits in a chair out of sight while the patient lies on a couch facing away. Why is this? In his new book "On the Couch: A Repressed History of the Analytic Couch from Plato to Freud", Nathan Kravis points out that this practice is rooted more in the cultural history of reclining posture rather than any empirical research. Kravis, clinical professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College, tracks the history of recumbent speech to ancient Greece, where guests reclined on couches to discuss philosophy. Here, he explains how the couch became an icon of self-knowledge and self-reflection.

Your book examines the cultural history of the couch. What drew you to this subject matter?

I’m embarrassed to say how long ago I began thinking of writing about the origins of the use of the couch in psychoanalysis. I began collecting advertisements, cartoons, and newspaper and magazine articles with couch illustrations more than 25 years ago. I’ve long been struck by the couch’s iconic resilience in the face of the long-heralded putative demise of psychoanalytic treatment. I am a practising psychoanalyst who values the use of the couch in the analyses I conduct, but it took me a while to realise that we analysts can’t explain on clinical grounds alone the peculiar arrangement of having the patient recline while the analyst sits, partially or completely unseen. If the aim is to be freed from having to attend to the conventional visual cues of face-to-face conversation, analyst and patient could sit in chairs arranged to face away from one another or set at a wide angle. You don’t need recumbent posture to achieve visual separation. Most discussions of the free association technique in the analytic literature skirt this issue. Indeed, I found that although most analysts since Freud have required or recommended using the couch, none seemed to really know why.

So I decided to seek explanations for the couch’s longevity by delving into the social history of posture. This took me into the history of furniture, art, fashion, and manners. Once I began to open up the topic in this way, I could start to formulate my thoughts about why those couch images I had been accumulating resonated so strongly with me. Lying on the couch while talking to me is a strangely powerful experience for many of my patients, as it was for me during my own analysis, but it wasn’t until I began to think in terms of the history of reclining in social settings that I could develop my ideas about how and why recumbent posture became such a cornerstone of analytic technique. In my book, I try to argue – visually, with a multitude of images, as well as semantically – that recumbent speech has a long and rich cultural history that is carried forward in the psychoanalytic set up. Freud’s decision to have his patients recline was shaped by this history, and he in turn shaped what recumbent speech has come to mean to us today.

What does the couch symbolise today?

Self-reflection, self-awareness, self-knowledge, and interiority. One sees this in religious iconography, portraiture, design and décor, literature, and popular culture. The analytic couch has also come to symbolise psychotherapy itself. This, too, I try to demonstrate visually and verbally. To say that someone is “on the couch” is widely understood to mean that he or she is in analysis. I trained in psychiatry in the 1980s. In those days, even those psychiatrists among my teachers who identified primarily as researchers or psychopharmacologists had couches in their offices. I think that’s because the couch was then – and perhaps still is – an iconic office fixture for the profession, so much so that even non-analysts hesitated to do without one. In any case, it’s clear that even among people with little or no interest in psychoanalysis, or any other form of "talk therapy", the couch is an icon that is immediately understood to stand for psychotherapy or, more generally, self-understanding.

How did the couch become so associated with self-discovery?

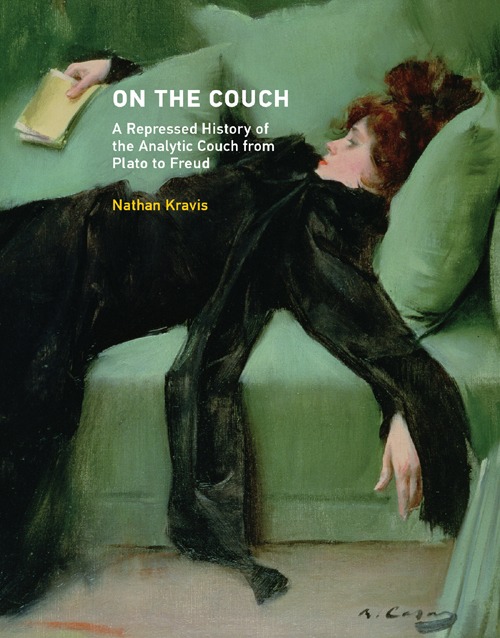

In my book, I argue that the sofa and the couch became the locus of intimate conversation and a favoured setting for the artistic depiction of interiority long before Freud adopted its use for treatment purposes. To my mind, this is epitomised by depictions of women readers, many of which are highly sexualised. I contend that the sexualisation of the woman reader defended against a threat even greater than the typical (and age-old) male fear of female sexuality – namely, male fear of female thought and imagination. Recumbent speech represents the affirmation in the presence of another of having a mind of one’s own. Psychoanalysis takes up this affirmation and runs with it, so to speak.

Where does this association of the couch with interiority begin?

It began with the Greeks and Romans. At least as early as the 5th century BC, the Greeks built sleep chambers in temples of the cult of Asclepius for the express purpose of dream interpretation. Posture has always been an important component of healing and spiritual traditions and practices. At banquets and feasts like the Greek symposion and the Roman convivium, guests reclined to dine and drink wine. Reclining in these settings was an expression of freedom, pleasure, intimacy, and luxury. With the notable exception of the Passover seder in Jewish custom, the reclining dining tradition faded with the end of the Roman Empire. But Neoclassical portraiture revived this trope, and, as I try to show in my book, recumbent posture soon came to mark the intersection of ease, comfort, eroticism, and interiority. In the 19th century, evolving ideals of domestic comfort began to be incorporated into medical settings and practices. I refer to this as the medicalisation of comfort. A striking example that I dwell upon at some length in my book is the open-air rest cure of the TB sanitarium, with the portable chaise-longue as its principal fixture. Hypnosis, but also many asylum-based somatic therapies such as hydrotherapy, cutaneous electrotherapy, and phototherapy employed recumbent posture. So the linkage of recumbence and cure was well established in the minds of patients and practitioners alike even before the advent of office-based medical practice. Here’s where one can clearly see a mutual influence between medical and psychological therapies on the one hand and trends in design and décor on the other.

How has this changed over time?

Many aspects of social life, including furniture, clothing, and manners, had to change and evolve for it to even become thinkable to lie down in the presence of another person to talk to him or her. Tightly corseted women, for example, or women wearing dresses with bustles could barely sit comfortably, let alone recline. A history of private conversation, if it were possible to write a coherent one, would ramify in dozens of directions all at once and would have to map an overwhelmingly intricate web of reciprocal influences and historical contingencies. Nevertheless, it is possible to identify a convergence of trends in 19th-century design, aesthetics, social mores, and medical practice that probably contributed to Freud’s notion that he should invite his patients to recline on his divan for their treatments with him.

Your book takes in elements of art history, medical history, and all sorts of other disciplines. How do you begin to research a work of cultural history like this?

I began as you might guess an analyst would: that is, by free associating to the cache of images I had collected over many years of meandering perusal. As I did so, I realised that I needed to construct in my mind a kind of furniture genealogy that would lead me from the reclining dining tradition of the Greeks and Romans to Freud and his distinctive couch. I looked at images of beds and benches, and noted how the bench morphed into the settee, and the settee into the chaise-longue, the sofa, and the couch. Then I began to map these changes onto portraits in paintings and early photography, and to correlate them with fashion history, and medical history. And, of course, there are dozens of couch cartoons from The New Yorker that are indispensable to an author with a project like mine. Choosing only five from among them for inclusion in my book was one of my hardest tasks! These cartoons are an incredibly rich resource, not only because it’s fun to satirise psychoanalysis and psychoanalysts, but also because it’s informative to think about what we need to laugh about in ourselves, both as patients and as therapists. Seeing what’s funny helps you see what’s seriously at stake. Couch cartoons mock our narcissism, our self-absorption, our imperiousness, our fears, our neediness. In this sense, they show a private self at work: disclosing, ruminating, obsessing, expressing. Recumbent speech puts everything into play, so to speak. Its strangeness is its power. We could spill a lot of ink elaborating on this, but sometimes a cartoon – or a painting, photograph, or some other image – says it better.

Although psychoanalysis is no longer the most dominant form of therapy, the couch remains a powerful symbol. Why is that?

The couch is a firmly entrenched social signifier and has entered the public lexicon of symbols for self-awareness and self-discovery. Because of the links between recumbent speech and cultural ideals of intimacy, privacy, and freedom of expression, the couch endures. One could almost say that the couch is healthier, or more resilient, than psychoanalysis itself! What does it mean that the couch continues to be such a robust symbol even as the popularity of psychoanalytic treatment has waned? My hunch is that such a symbol has perhaps taken on new life in our digital era in which our relationship to privacy and interiority clashes so strongly with our addiction to the internet and our always-on ‘smart’ devices. You don’t have to be in treatment to value self-awareness, but psychoanalysis remains a special path toward interiority. Despite the ups and downs of psychoanalysis, the analytic couch perseveres as a cultural icon because the felt need for spiritual nourishment, inwardness, and freedom – including freedom from our devices – is as urgent now as it ever was.