This article is a preview from the Spring 2018 edition of New Humanist.

In 2004, shocked by the prevalence of climate change deniers, the cultural theorist Bruno Latour – who was best known for inaugurating the field of “science studies”, which sought to examine the truth claims of science by exploring how those truths were established in terms of their social, political and cultural foundation – wrote an article entitled “Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern”.

In the article, Latour shared his concern that the field of cultural studies, with its “weapons” of critique, deconstruction and relativism and its rejection of grand narratives, stable definitions and eternal truths, had been complicit in creating a world in which all knowledge was seen to be relative, partial, site-specific and therefore doubtful. Having himself argued that all facts are “constructed”, Latour now worries that he has gone too far. Citing an op-ed in the New York Times, in which a Republican senator argued that the way to gain public support for climate change denial is to artificially maintain a controversy by continuing to “make the lack of scientific certainty a primary issue”, Latour notes “I myself have spent some time in the past trying to show ‘the lack of scientific certainty’ inherent in the construction of facts.”

Latour worries that by arguing that there is no such thing as “natural, unmediated, unbiased access to truth” and that we “are always prisoners of language, that we always speak from a particular standpoint”, we have made any claims to truth the objects of suspicion. The apotheosis of this type of thinking is represented by Jean Baudrillard’s The Spirit of Terrorism, in which Baudrillard implies that “the Twin Towers destroyed themselves under their own weight, so to speak, undermined by the utter nihilism inherent in capitalism itself”.

It is the horns of a dilemma that many of us find ourselves on now. Those of us who are used to critiquing concepts such as “truth” find ourselves looking on as the very idea is undermined in the era of Trump, fake news and Brexit. It seems we have deconstructed truth just when we needed it most.

* * *

Latour’s 1979 book Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts, which he co-authored with the British sociologist Steve Woolgar, is generally seen as inaugurating the Science Wars, a pitched battle between scientists and cultural theorists over the objectivity of science. Woolgar and Latour spent two years at the Salk Institute for Biological Sciences in San Diego, California. They went in as anthropologists, to observe a laboratory in action, and to examine the social factors – political, interpersonal, financial and so on – at play in scientific life, which had, in their argument, seen these elements as outside scientific thought; or, at best, the scaffolding which needed to be erected before the true work of science began.

Latour and Woolgar aimed to carry out a “sociological deconstruction” of science. Of course, we are all familiar with the idea that funding and funding priorities affect what is researched, and therefore what facts are investigated, where facts are defined as “things in the world”. A country that prioritises its military will generally find out more about nuclear reactions than a country that prioritises food supply, which may learn more about horticulture.

But the authors wished to go further than this. It was their contention that science operates not by “investigating” or “revealing” facts – but by “constructing” them. Science is interested in “explaining” situations: given a certain set of circumstances, a certain outcome occurs. Latour looks in some detail at how a scientist gets to the point of conducting an experiment. There is not only the scientist’s qualifications and authority, but also the historicity of science: why this experiment now, which of society’s needs are being met, how did the necessary equipment come to exist, and so on. An experiment is carried out at a particular time, in a particular place, and these are not incidental factors. For example:

Our scientists, when noticing a peak on the spectrum of a chromatograph, sometimes rejected it as noise. If, however, the same peak was seen to occur more than once (under what were regarded as independent circumstances), it was often said that there was a substance there of which the peaks were a trace. An “object” was thus achieved through the superimposition of several statements or documents in such a way that all the statements were seen to relate to something outside of, or beyond, the reader’s or author’s subjectivity.

The object was made to exist in order to explain the “peak” on the spectrum. Had other explanations been available, then no object would have needed to be constructed. Had the equipment been different, the peak might not have occurred, so again no object would have been required. Had the study which was taking place been a different study, where such peaks were unimportant, the object would not have been “discovered”. Had funding for this project not been granted then the peak would never have existed, and so the object would not “exist”.

To take a favourite example of Latour’s, which he examines in his later books Pandora’s Hope and The Pasteurization of France, it is popularly held that Louis Pasteur “discovered” microbes. Latour examines in detail the ways in which Pasteur had to galvanise various forces in order to make his theory pre-eminent: farmers, politicians, other scientists, industrialists. There were competing theories of how a disease spreads: “scientific activity is not ‘about nature’, it is a fierce fight to construct reality,” Latour writes. Had the social conditions been different, microbes might not have been hypothesised. An object was “constructed” to explain a set of circumstances. It is then regarded as “out there”. As Latour puts it, “the more Pasteur works, the more independent the substance becomes.”

Once a fact has been constructed, it then becomes part of science, and is no longer questioned:

A fact only becomes such when it loses all temporal qualifications and becomes incorporated into a large body of knowledge drawn upon by others ... Every time a statement stabilises, it is reintroduced into the laboratory (in the guise of a machine, inscription device, skill, routine, prejudice, deduction, programme, and so on), and it is used to increase the difference between statements.

Latour came to call this operation “black boxing” – the fact is no longer disputed, it becomes another tool in the scientists’ toolkit, the same as, say, a chromatograph.

To say an object is “constructed” is not, however, to argue that it is not real. We are surrounded by objects constructed by humans. But with the objects that surround us we are much more open to the idea that they are the result of factors that lie outside themselves. Television could not have been invented in 1864 when Pasteur was discovering pasteurisation. It is a nonsense to speak of television as having always existed but just needing to be discovered.

Latour argues it is also nonsense to speak of microbes always existing, waiting to be discovered. It is possible that there were other models of infection that would have had as much, or more, explanatory power, or which fitted better with other contemporaneous theories, or would have been better funded. Microbes as a class might never have been required, and the state of affairs which led to their instantiation might not have occurred. To posit their existence is an act of “retrofitting the past, in the same way that the Old Testament was retrofitted by Christians to foretell the coming of Christ”. An experiment takes place, a gap in the knowledge is found, an object is hypothesised to fill the gap, and future experiments produce the same gap, and thus confirm the object.

* * *

Latour and Woolgar’s work threw down a challenge to the scientific establishment, which responded immediately. The debate was fierce, sometimes sophisticated, often not, and broke along broadly epistemological lines: between those who argued that facts exist “out there”, independent of human thought, and those who argued that all knowledge is “human knowledge”, socially constructed, and any agreement between our “facts” and the “real world” is by convention. As Latour later argued:

We have taken science for realist painting, imagining that it made an exact copy of the world. The sciences do something else entirely, paintings too for that matter. Through successive stages they link us to an aligned, transformed, constructed world.

All intellectual disciplines have a duty to critically re-examine their founding principles regularly. But science, with its operating myth of “the search for truth”, resisted this with particular ferocity. A conference, “The Flight From Science and Reason” at the New York Academy of Science, was organised by the scientists Paul R. Gross, Norman Leavitt and Gerald Holton, while the former two published Higher Superstition: The Academic Left and its Quarrels With Science.

“Postmodernists” became a catch-all term for cultural theorists who were accused of undermining the entire basis of science.

To argue that facts are socially constructed is to argue that they are mere matters of opinion – and matters of opinion are what the laboratory prides itself on eliminating. Science regards itself as an objective discipline, from which subjectivity (the mess of life) is expelled in order to cordon off an area which “finds out things” about the world.

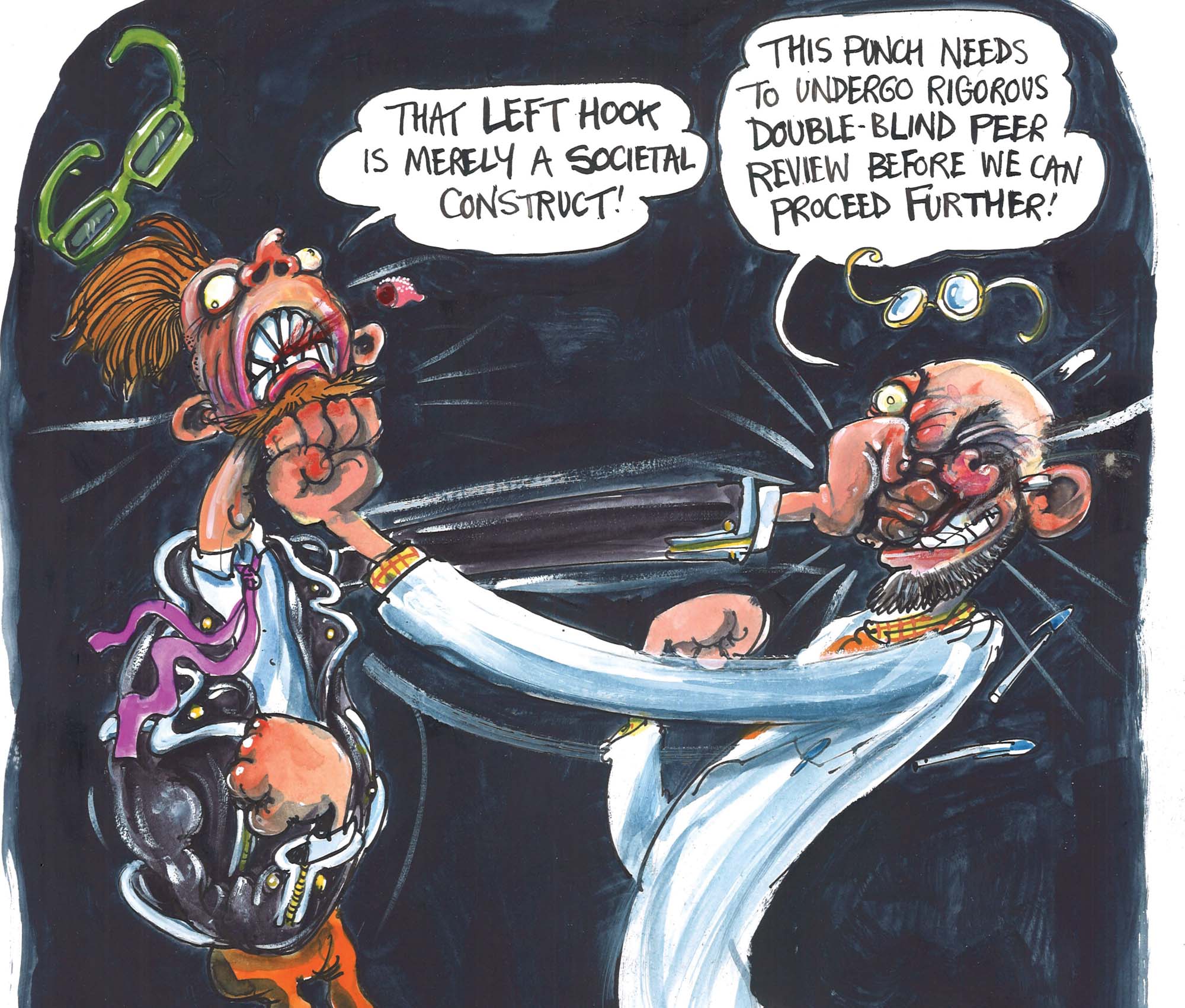

The “war” culminated in a 1996 hoax paper by the mathematician and physicist Alan Sokal, entitled “Transgressing the Boundaries: Toward a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity” which he submitted to, and had accepted by without question, the cultural studies journal Social Text. The article used familiar postmodern tropes to put forward a nonsensical argument in which quantum theory is seen as providing a central foundation for postmodern theory. For Sokal, such theory is gibberish.

The tone of the debate had, frankly, been set by Latour’s book itself. While its conclusions are fascinating, Laboratory Life is snarky, with the odd bitchy aside (“even insecure bureaucrats and compulsive novelists are less obsessed by inscriptions than scientists”). The conceit of the book, in which a putative anthropologist, knowing nothing about a laboratory, goes in to watch the activities of baffling humans, sets a tone from which the book has trouble escaping. Scientist are referred to as “people calling themselves scientists” and as “tribes” (“whereas other tribes believe in gods or complicated mythologies, the members of this tribe insist that their activity is in no way to be associated with beliefs, a culture, or a mythology. Instead, they claim to be concerned only with ‘hard facts’”), while the accusation of gibberish is hurled first by Latour:

But he [the anthropologist] felt entirely unable to grasp the “meaning” of these papers, let alone understand how such meaning sustained an entire culture. He was reminded momentarily of an earlier study of religious rituals when, having penetrated to the core of ceremonial behaviour, he had found only twaddling and waffling. In a similar way, he had now discovered that the end products of a complex series of operations contained complete gibberish.

It is of course necessary for any field, whether it be science, cultural studies, farming, or shelf stacking, to have a technical language which appears opaque, obscure or unnecessary to someone from outside their field. Neither Sokal nor Latour would argue that the specialised terms they use (and need) for their work be purged. Accusing each other of gibberish is not helpful. Latour has in fact recently acknowledged: “There was some juvenile enthusiasm in my style ... I certainly was not anti-science, although I must admit it felt good to put scientists down a little.”

For scientists, to assent to Latour and Woolgar’s argument was to assent to relativism – that any version of the truth has equal weight to any other. This was to go far beyond the arguments of, for instance, Thomas Kuhn, whose 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions had caused a similar stir. Kuhn had argued that scientific progress was not linear but episodic, and a theory was only replaced when a more coherent model was found, or when it collapsed under its own contradictions. A “paradigm shift” would occur, as when Copernicus’s theory of the heliocentric universe replaced the Ptolemaic system. The Copernican system was more “coherent” – with itself and with other emerging systems like Galiliean motion.

Kuhn was also accused of relativism, having argued: “In the sciences there need not be progress of another sort. We may, to be more precise, have to relinquish the notion, explicit or implicit, that changes of paradigm carry scientists and those who learn from them closer and closer to the truth.” However, Kuhn, in a postscript, still held the position that scientific discovery is a “unidirectional and irreversible process” and gets better at solving puzzles. Latour and Woolgar were agnostic on that point.

* * *

Relativism is, broadly, the view that any position we hold – what is right, what is good, what is true – is the product of a framework of assessment, a convention, and that its authority is confined to its context. It has, of course, always had a place in philosophical thought – pre-dating Plato – since any claim to truth must address the problem of relativism. Twentieth-century philosophy (especially continental philosophy) made it central to fields such as post-structuralism, deconstruction and postmodernism. A claim such as “truth is a matter of context”, has opened the way for new thinking about notions such as gender and race, with positions that were seen as natural shown to be the product of, for instance, power.

By denying truths that are eternal or ideal, this way of thinking has been accused of allowing for “anything goes”. More recently it has been seen as enabling – or predicting, depending on your position – a world where all competing positions have equally valid truth claims, leading to such things as “fake news”.

For instance, in his recent book Post-Truth, the journalist Matthew D’Ancona also accuses “postmodernism” – which he uses for thinkers as diverse as Foucault, Derrida and Lyotard – of gibberish, and drawing parallels between Baudrillard’s argument and Donald Trump’s false assertion that he saw people cheering when the Twin Towers came down. “It is an arresting reflection that, etched into the long Parisian paragraphs of convoluted post-modern prose, so often dismissed as indulgent nonsense, was a bleak omen of the political future,” writes D’Ancona.

This is to argue that the notion of “truth” is disposed of completely by “postmodernists”. But to say that truths aren’t eternal is not to deny that “truth” functions in our society. If I was to ask you to give a “true” description of your kitchen, you could, stamina allowing, continue to tell me about it to infinity. But your description would be different from that of the hygiene inspector standing next to you. Or the poet next to him. Each would be a valid description, as opposed to the next person along yelling the word “turtle” over and over again. There are socially accepted standards or norms that would make one description better than another.

To critique truth is not to say that it does not exist, that it does not have purpose. It is, rather, to point out how it came to be, to note its purpose, to understand its function, and to acknowledge that it has a context. Trump, when he accuses people of cheering at the fall of the Twin Towers, or Barack Obama of wiretapping him, is not arguing that there are different truths and one is no better than another. He is simply lying.

Lies have, of course, always been a tool of government – propaganda has always been with us. What has been a shock to many of us in the last two years has been waking up to the idea that propaganda functions in such a way as to appeal to the emotional responses of its intended audience, rather than what we imagined to be their search for truth. In the age of the internet, multifarious news sources and so forth, we expected that a greater access to information would lead to people becoming more informed, and, having become so, to make more informed choices. But propaganda has continued to function as it always has, but with greater reach. To say that Trump, or those who lied to the public about the potential gains from Brexit, are using the tools of postmodernism is simply incorrect. They are using the tools of propaganda.

What is “postmodernist” is the ability to argue that, when Trump makes such claims, and they are believed to be true by a certain segment of the population, we can analyse why, by looking at factors such as gender, economics and race. Or why, if another segment of the population believes the claims to be untrue, it doesn’t seem to matter.

In “Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam?”, Latour notes that those members of society who remain suspicious of facts and “experts” also tend to hold to conspiracy theories, which are in a sense a “truer truth” – whether it is Trump’s notion of a “shadow government” or the idea that all of the financial difficulties suffered by the UK are the fault of a dark place called Brussels. To this way of thinking it cannot be the case that the Twin Towers came down due to a small band of highly motivated terrorists. The universe cannot be so random. It must have been the US government itself. To put forward or believe in a conspiracy theory is to search for a truth. It is not that they can’t handle the truth – they can’t handle the relativism.

* * *

In a 2017 interview with Science magazine, Latour asserts that it is now time for intellectuals to help “regain some of the authority of science”. Dismissing the Science Wars as phoney, Latour argues that now “we are indeed at war. This war is run by a mix of big corporations and some scientists who deny climate change. They have a strong interest in the issue and a large influence on the population.” For Latour, the answer does not lie in a repudiation of his notion that truths are constructed. Yes, he now thinks it is time to redirect his energies. However, his cosmology – to use a useful old term – stays intact. For Latour, facts, be they scientific or otherwise, remain constructed. They do not exist independent of human reality. But this is precisely their power.

For Latour, it is a fundamental error of thought, pre-dating science as we know it, to separate the world into subjects and objects, to regard the world as “out there”. This is why Latour has always avoided questions of epistemology, as they reinforce a dualism he wishes to move beyond. We need to re-establish a relationship with reality in which our investment is acknowledged.

To regard something as an object is to regard it as something which does not concern me except, perhaps, as an object of study. This is one of the tricks of the current political climate, to have us regard certain things as mere “objects” that we have no investment in – climate change is an object to be proved or disproved elsewhere, refugees are objects to be dealt with by economic calculations.

Latour draws on the German philosopher Martin Heidegger’s distinction between an object and a “thing”. The latter is a gathering of attributes that includes human “investment”. This is not the same as an object, which is what science studies. For instance, humans have a sun which “rises and sets” in a way that it does not for science. The former is a product of our common sense. It concerns us immediately. Our mistake has been to move from this to a world of objects.

Latour again refers to the destruction of the Twin Towers where “suddenly at a stroke, an object had become a thing, a matter of fact was considered as a matter of great concern.” For Latour this shift is crucial. If climate change, or a refugee crisis, becomes a matter of concern rather than a matter of fact, then we enter into a relationship with it; we care. To take climate change seriously, we “literally, not symbolically, have to manage the planet.” Latour writes:

The critic is not the one who debunks, but the one who assembles. The critic is not the one who lifts the rugs from under the feet of the naive believers, but the one who offers the participants arenas in which to gather. The critic is ... the one for whom, if something is constructed, then it means it is fragile and thus in great need of care and caution.

It is the job of social critique to continue to examine ways in which power, propaganda and political and economic systems function; to make objects of fact things of concern. To conflate the lying of the Trump era with the “questioning of truth” is to become complicit in a neat trick – just as governments can withdraw resources and blame it on outsiders, so barefaced lies are told and blamed on “postmodernism”.

But it is precisely the tools of postmodern and deconstructive thought we need now. After all, as Latour points out, “the opposite of relativism is totalitarianism”.