This article is a preview from the Summer 2018 edition of New Humanist

One of the reasons I delayed having a laser cataract operation was because I’d grown so very weary of learning from my elderly friends about its transformative effect. “All of a sudden I could see colours as I’d never seen them before,” confided Dave Hepworth over a pint. “A new world came into view.”

I always did my best to look enthusiastic but could never quite generate a similar enthusiasm about the prospect of entering an altered visual universe. Part of my reluctance was down to Richard Burton. Some years before the great actor and hell-raiser died, he announced that he had given up drinking. “It was a revelation,” he told a gossip columnist. “Suddenly I could see the world as it really is.”

My old friend Stan Cohen was magnificently unimpressed. “Who on earth,” he said, “wants to see the world as it really is?” It was powerful endorsement of the benefits of alcohol but also a very good reason for learning to live with my ever-developing cataracts. Quite frankly, I’d grown to like the veil that my blurred vision cast over the hard edges of the material world. I’d become accustomed to not recognising friends unless they were within kissing distance, cheerfully resigned to my constant failure to distinguish between the villains and the heroes on television.

But several months ago, after a particularly distressing literary event at which I’d failed to recognise both Roger Scruton and Peter Hitchens, and had ended the evening by mistaking the hostess for my wife, I succumbed. And yes, my friends had been quite accurate. Colours were certainly brighter and more demanding of attention and if I stood on a chair I could spot the London Eye from my window.

But something far more disturbing had also occurred. When I took my first bold look in the bathroom mirror a couple of days after my double laser operation, I realised with a shock that I no longer resembled Samuel Beckett. Although no doubt further research is needed, it must surely be near to a well-established scientific fact that all of us, at one time or another, have decided that we resemble a famous person. My ex-partner, for instance, believed, even as she entered her middle years, that she was a dead ringer for Leslie Caron in Gigi. This isn’t necessarily a narcissistic enterprise. I well remember the wonderful Liverpool comedian and novelist Alexei Sayle bemoaning the fact that while other boys at his school could boast some sort of passing resemblance to John Lennon or Mick Jagger, he had to face the relative social ostracism that came from looking like Berthold Brecht – “a fucking East German poet”, as he vehemently used to protest on stage.

In my own childhood I briefly entertained the idea that I might grow into someone who looked rather like Stewart Granger but it wasn’t until my mid-50s, when I’d assumed a pair of rimless glasses, swept back my mop of greying hair and pulled on a black rollneck sweater, that I was twice told by relative strangers that I looked “awfully like” the celebrated author of Krapp’s Last Tape.

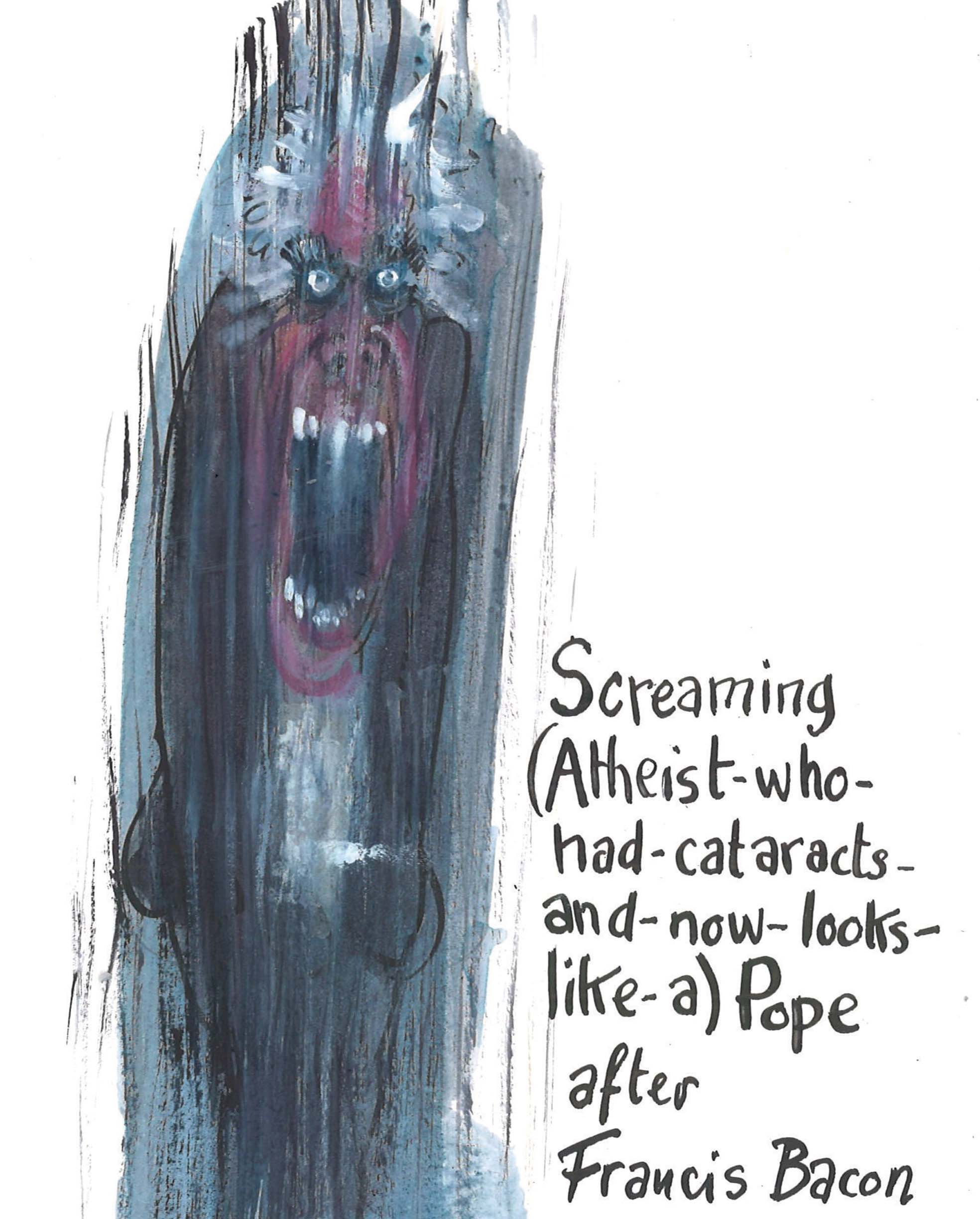

But my new crystal clear eyesight made the change impossible to ignore. I was now the spitting image of Pope Benedict the Sixteenth. It’s hardly the ideal alter ego for a professional rationalist so I suppose I can only be grateful that Benedict retired from public papal life some years ago, and now, according to reports, spends his time quietly cultivating organic oranges in some remote corner of Vatican City. Still, for greater security, I’ve also endeavoured to mask my newfound resemblance by adjusting my hairstyle and eschewing anything in the wardrobe that resembles a cassock.

So far, only my old radio producer Charles Noakes has been entrusted with my new identity. He’s eminently trustworthy although there was an awkward moment during a recent dinner-party discussion of Jeremy Corbyn when I allowed myself to sound more than usually dogmatic.

“OF COURSE HE’S NOT ANTI-SEMITIC.”

Noakes piped up in the mildly embarrassed silence.

“Best not to argue with Laurie,” he cautioned across the table. “After all. He is infallible!”