This article is a preview from the Winter 2018 edition of New Humanist

A year ago I sat in Wimbledon Library interviewing the novelist Ali Smith for a book festival, about how Britain had changed since 2010 and especially since the EU referendum. Her novel Autumn explores the strangeness – the rise in anti-immigrant hostility, the privatisation of public services and spaces – but also the role and power of artists to show us new ways of seeing the world around us. I confessed to the audience that I felt now more than ever the need to read novels and see plays and exhibitions to take me out of the ugliness of daily news. Not as an escape, but as essential nourishment in an era of energy-sapping shouting masquerading as political discussion. The audience called out yes and nodded enthusiastically in agreement.

It is easy to be smug about libraries and the worthiness of the arts. Indeed there is a kind of reverse snobbery which rebukes middle-class critics and commentators for fetishising their supposed “improving” power over reality TV. And yet the choices artists are making now reveal a greater sense of wanting to better engage the public.

This is evident on both sides of the Atlantic. Since his 1989 break-out hit Do the Right Thing, Spike Lee’s political films have often worn anger with pride, alongside the beautiful visual compositions. But his recent Blackkklansman uses comedy to advance its critique of racism in America past and present. The two central characters, detectives who infiltrate a group of white supremacists, exchange jokes at their desks like we’re watching a wisecracking 70s TV cop drama. There’s a delicious dance sequence in a groovy nightclub, just for the joy of it. And then at the end, Lee hits you with the final five minutes of raw news footage from Charlottesville last year, where white supremacists rallied and a young woman was murdered. This is a movie with a lengthy eyewitness account of a lynching. But it’s somehow also a feel-good film you could watch again and again, rather it being simply an exercise in pain and fear.

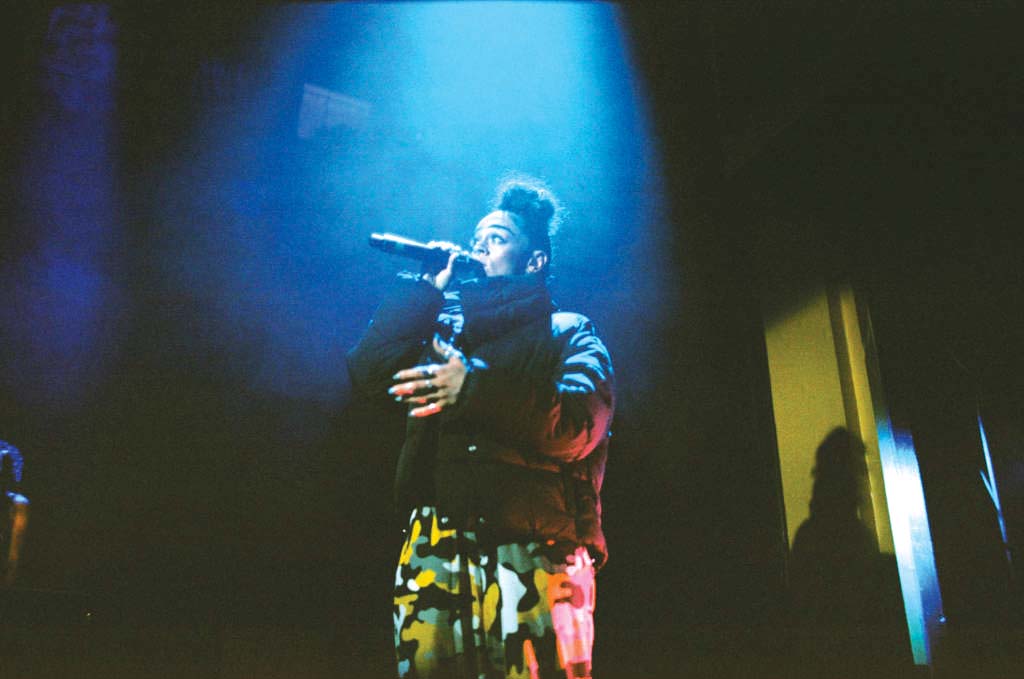

British theatre, despite some data suggesting a year-on-year fall in regional ticket sales, feels like it’s thriving with ideas, new writers, directors and themes. Take Debris Stevenson’s Poet in da Corner, which brings the power of grime and a new young audience to London’s Royal Court; the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Tartuffe, set in modern British-Pakistani Birmingham; Steel at Sheffield’s Crucible; and Tanika Gupta’s Tigers and Lions, about the Indian independence movement, at Shakespeare’s Globe in London.

But at a time when social media has unleashed a new unrestraint in public discourse – individuals being targeted and trolled and threatened from the safe anonymity of a keyboard – theatre is also a daring experience, a physical communion of disparate strangers. Do audiences know where the boundaries are any more? Some immersive shows where audiences are encouraged to feel part of the action, such as the flapper party staging of The Great Gatsby in London, have had to come up with new security measures to tackle a number of sexual assaults on actors.

Even in a traditional theatre experience, I noticed the atmosphere of social media infecting that bastion of polite middle England, the Alan Bennett play, at a performance of his latest work Allelujah! at London’s Bridge Theatre. There is a scene when the diligent Indian-born Doctor Valentine, played by Sacha Dhawan, addresses the audience directly, recounting his callous treatment by the Home Office, which has marked him for deportation. “Oh, England, open your arms before it’s too late,” he declares. There is no line in the play that more clearly sounds like Bennett’s own viewpoint. The moment the words were out, a strong middle-class male voice piped up from the audience in an exasperated tone, “Oh, for God’s sake.” It was a remarkable moment. I can’t be certain of the context as I couldn’t see the speaker, but it sounded unmistakably like the released fury of someone who might be tweeting while watching television, obviously unimpressed with Bennett’s arguably simplistic pro-immigrant sentiment. It was unpleasant to hear such words shouted at a British Asian performer.

I shared my story with Nikolai Foster, the artistic director of Leicester’s Curve Theatre. “People find clever ways of concealing really risible beliefs,” he told me, citing an audience member who came up to him in an interval about the casting of the male lead in a recent production of Grease. “The best actor for the role happened to be black, but [the audience member said] ‘There’s something not quite right about Danny. I can’t quite put my finger on it’.”

It is more subtle than the controversy that arose when the Daily Mail’s Quentin Letts wrote a review speculating that a black actor had only been cast in a Royal Shakespeare Company production of a Restoration comedy, The Fantastic Follies of Mrs Rich, because of his ethnicity. The RSC and many other prominent figures in the theatre industry hit back, saying that Letts’s comments were racist and deeply troubling.

At a time when television’s star offerings like The Crown and ITV’s Vanity Fair mine a distinctly mono-ethnic vision of the past rather than the present, British theatre is taking a refreshing stand. One example of this is colour- and gender-blind casting, which has been introduced at Shakespeare’s Globe. In addition, there are several stage industry initiatives aiming to broaden the range of stories, and show a better representation of all experiences; aiming for 50:50 gender balance in writers, casting and directors, making a conscious effort to cast more LGBTQ performers and actors with disabilities.

As a presenter of BBC Radio 4’s Front Row, a job that involves watching and debating the big trends in TV, film and theatre, I’ve been struck by the contrast between the range of new writers and talent emerging from drama schools, and the familiar formats and remakes being churned out by our biggest national television production houses. Seeing the Georgian frocks of ITV’s new autumn offering Vanity Fair on the cover of the Radio Times, even I couldn’t resist tweeting: “One day we’ll write social history books about how during one of the most dramatic periods of social & political tension, despite all the untold stories & a richly diverse range of young talent, TV execs kept remaking the SAME period dramas.”

This was my own dip in the pool of Twitter’s culture wars and proved what you’d expect. Thousands retweeted it in support, including many prominent historians, writers, directors and actors such as Adrian Lester and Lenny Henry. The responses included one from Vanity Fair actress Elizabeth Berrington: “I’m in it but I most wholeheartedly agree with you!” It wasn’t an entirely positive response, however. After being retweeted by a prominent right-wing talk radio presenter looking to draw the attention of their substantial following, there came racist insults. More than one prominent middle-aged white male culture writer felt the need to explain to me that Vanity Fair was a great book.

A different kind of period drama is also emerging, though. Some writers are finding interesting parallels between the past and today’s gig economy and #MeToo struggles. One such play is Vinay Patel’s An Adventure, which debuted at the Bush Theatre in London this autumn. It casts a fresh eye on the 1960s generation of Asian immigrants who migrated via Kenya to Britain, and highlights the bravery of Asian women strikers in the 1970s, such as at the longrunning Grunwick factory dispute in north-west London.

What is striking looking back at the 1980s, when Margaret Thatcher’s government brought in major funding cuts and fundamental ideological changes in how arts institutions had to operate, is how much money was still going into culture compared to now. Recent cuts by local authorities have been massive. In 2012 Newcastle Council even tried to cut their entire arts budget to zero in the city. But eight years on from the start of austerity economics and with National Lottery funding shrinking, many local theatres have adjusted and found ways to thrive. Art can still be angry, but it is about putting joy into audiences and bums on seats.

At the Curve Theatre in Leicester, Nikolai Foster balances touring crowd-pleasers, such as his musical of An Officer and a Gentleman, with modern tales that draw on local stories. Memoirs of an Asian Football Casual explores how British Muslim teenager Riaz Khan found a sense of identity and belonging with Leicester City’s infamous Baby Squad of nattily dressed football hooligans in the early 1980s.

Foster thinks this drama offers fascinating parallels to the present political debate over immigration and Brexit. “It feels very relevant to where we are today,” he told me. “We were able to react to the Brexit vote with something historical that worked. A teacher said the boys in her comprehensive had never been more switched on than working on this. We sent them a rehearsal video as there was so much red tape to theatre trips. That level of engagement was so valuable.”

At Curve, Foster says there is a loyal core of affluent white attendees who may well have voted for Brexit, but are still up for seeing alternative perspectives. “They absolutely loved it. There were in tears at the end. Audiences are growing and you can feel their appetite to be challenged, to see things that are provocative. And they’re embracing the idea that theatre is a political art form.”

If Foster has criticism for anyone, it’s for some of the London art critics who sneered at Curve for creating An Officer and a Gentlemen. He told the Stage newspaper in May 2018: “It’s disingenuous too, and inverse snobbery ... they shoot us down for doing something popular, but it’s popular work that gets them on the train up here.”

I asked Foster about this. “There’s a lack of understanding,” he told me. “An Officer and a Gentleman, which has toured the nation to packed houses, has paid for Memoirs. It’s constantly balancing the popular and the commercial . . . Memoirs charts immigrants arriving and the children in the late 70s when the National Front had a real grip in the city.” Though he says some “nastiness” remains, Foster believes that as a result of having to deal with that racial violence then, modern Leicester is more at ease with its diverse present than some other cities.

It feels like we’ve come a long way since, in the aftermath of the EU referendum, the new director of the National Theatre, Rufus Norris, commissioned My Country – a verbatim theatrical piece based on interviews with voters around the UK about Brexit. It was an acknowledgement that the arts establishment and the London arts world in particular had not fully appreciated the strength of anti-EU feeling.

“Theatre gives us an opportunity to genuinely change people’s lives,” Foster remarked, as he reflected on the reaction to a dance performance by associate artist Aakash Odedra. “A working-class white bloke had come along because his company had sponsored the event. He came up to me after and asked if I was involved and told me: ‘I was watching this Asian lad dancing and it was one of the most breathtaking things I’d ever seen in my life. I didn’t realise you could get lost in someone’s performance that way.’ That happens on a daily and weekly basis.”

At this year’s Wimbledon Book festival – where I’d interviewed Ali Smith the year before – my guest was the novelist Lionel Shriver, whose excursions into commentary include include what were widely seen as mocking efforts to improve diversity in publishing, and calling men “wusses” for not fighting back harder against sexual harassment and assault allegations. Our discussion reminded me that there is no obligation for writers to offer a comfort blanket in angry times. But to pick up a book, or to enter a fabricated world on stage or in film, all offer a kind of escape and a chance to re-enter the real world refreshed.

“Despite the madness,” Foster concluded, “I think that all of the xenophobia and racism and nastiness that’s been unleashed – I think it’s fuelled theatre and arts to be more provocative and searching. To ask, what can we do better? It’s put fire in our bellies.”