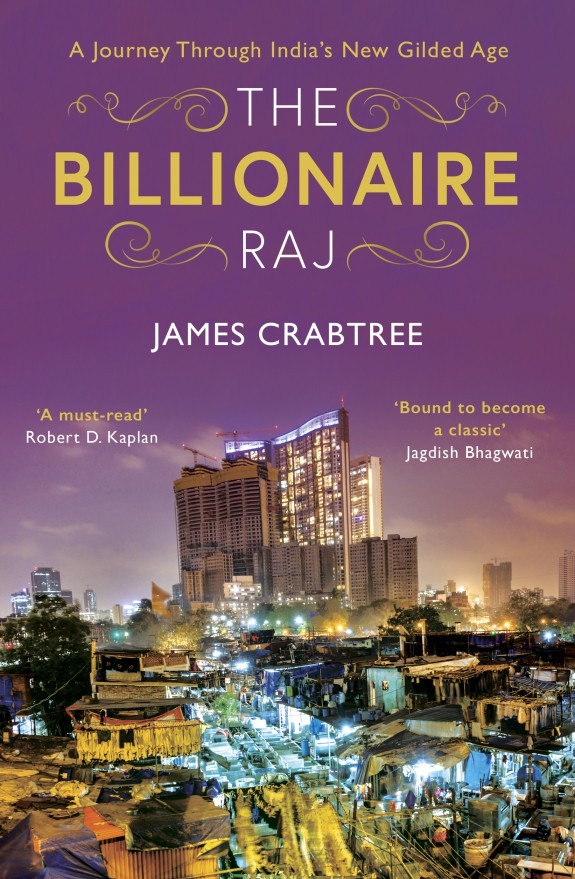

India has experienced an explosive economic rise, which at the same time as increasing its power on the world stage has driven inequality to new extremes. Even as tycoons exert huge power over business and politics, millions remain trapped in slums. Corruption is endemic. Can India become the world's next great superpower? In his book "The Billionaire Raj: A Journey Through India's New Gilded Age" (Oneworld), journalist James Crabtree, who spent five years as Mumbai bureau chief for the Financial Times, explores this question.

Why did you write this book?

I used to joke that what I was doing was hardly unprecedented, given it's another book about India from a white British journalist, of which there have been a fair number.

Typically the way that people from outside view India is through the political capital, not the financial capital, and so in five years based in Mumbai rather than Delhi, I saw a different kind of India – one that was about wealth and finance and the power that comes from money, as opposed to the power that comes from votes. As a Western journalist for a global publication, I was lucky enough to get very good access to what in the book I call the Bollygarchs – the new super-rich strata that has grown in India over the last 20 years. And so I thought I had a perspective that even as an outsider, would be a useful contribution to the wider debate about India's future.

We all know in some basic sense that India is important, but we don't think about it very much. We think a lot about China. We spend a lot of time thinking about really quite small countries like Hungary, Turkey, Italy. India is underappreciated for its enormous significance for the remainder of the century, at the moment in which China is degrading into a form of Leninist autocracy. We all have an enormous stake in the success of India as a society, not simply from the basic point that there are 1.3 billion people who live there, and therefore at any level it is significant what happens there. But also we in the West who are Democrats, who are liberals hope that the Indian tradition of liberalism and tolerance and secularism will continue to flourish. At the moment there's good news and bad news on that front. My argument in the book is that India is going to play a critical role in the future of the world over the next century.

Why do you think India is underappreciated?

There is lot going on in the world at the moment, and I'm not saying this is anybody's fault. You have Trump, the rise of China, war in Syria. My argument is that over the long term, the success of Indian democracy and whether or not India becomes a tolerant free market parliamentary democracy by the middle of this century, or whether it could take another path, is one of the most consequential things for the future of the world. And so understanding the stage that India is going through is something that we should all be interested in, in much the same way that we are interested in the internal politics of America or China. These things have enormous consequences far beyond their borders.

How does the Indian tycoon class interact with politics?

The tycoon class and the political class are intimately wrapped up with one another. If you are an industrialist, you need politicians to do almost anything - if you want to build a steel plant, a road, an iron ore mine, you need things that only the government can provide. If you're a politician, you need to win elections, which are very expensive. There's no state funding of political parties. According to one estimate, the last election cost $5 billion. Almost all of that money was provided illegally under the table by large businesses, given to the political parties' elite - a quasi-corrupt system. One way of describing this is crony capitalism. It is writ large in the relationship between politics and capital. But you also have individual cases where the business and political elite will collude with one another in order to enrich themselves, not to deliver the public good. This was at its zenith maybe 10 years ago; there was a series of jaw dropping corruption scandals. It was called the “season of scandal”, in which telecom spectrum or mining rights, whatever, were gifted to the tycoons who owned the big conglomerates.

Under the current Prime Minister Narendra Modi, elected in 2014, the most eye catching scandals have stopped. He has mostly put a stop to the worst of it. But India still has big problems of corruption that it needs to tackle in all areas of public life.

Modi was elected promising to end corruption. What is his response to this crony capitalism?

He has stopped the most egregious crony capitalism in Delhi, which was happening almost literally around the Cabinet table. No one accuses Modi himself of being corrupt, much like the last prime minister. He is an honest man, and to some degree he has read the riot act to these tycoons. Some of them have been frozen out. But Modi's progress cleaning up corruption has been mixed. He introduced an initiative called de-monetisation, when they scrapped most of the banknotes. This was a crazy initiative that in theory was designed to combat corruption but which did nothing of the sort. Underlying this you have the problem that I mentioned before about the nature of funding politics, which is unsolved.

The rise of the super rich has gone hand-in-hand with growing economic inequality.

This is a story about globalisation. India became independent from Britain in 1947 and then for about 40 years, closed itself off from the world under the socialist planned economy which they called a “license raj”, because it was controlled by licenses, quotas and permits which decided how much you could produce if you were a business. They literally said you could only produce ten cars, or whatever it was. That only ended in 1991, and India opened itself up to the world. In a very simple sense, money came in, India re-globalised, it re-entered the global economy and that played havoc with all sorts of things - the regulatory system was not able to cope. India's economy started growing very quickly, which meant that things became more valuable, which meant that the returns for corruption were much higher. It also meant an extraordinary explosion of wealth at the very top of Indian society. The top 10 per cent of Indian society have done very well over the last 20 years. Although in absolute terms, the other 90 per cent have done much better, in relative terms have fallen farther and farther behind. That that gets more profound the further down you go.

India has always been a very unequal country. You have the caste system which everybody knows about. But you also have inequalities based upon religion, language and region. Everyone knows India is an unequal society but people haven't noticed how much more unequal it has become.

This problem of inequality itself is a profound one. If India wants to follow the countries of East Asia through a successful development path, moving from poverty to middle income and eventually to becoming a rich country sometime in the second half of the century, it is unlikely to be able to do that unless it fixes three big problems: the rise of the super rich and the inequality that come with it, crony capitalism, and dysfunctional investment model that underpins its growth.

Modi’s background is in the Hindu nationalist movement. How does negotiate his relationship to the more extreme elements of the movement?

You have to start from the position that Modi’s background is as a member of the more extreme elements of the Hindu right. That was his advancement into politics. He has a poor background. In this sense he's a model of Indian social mobility. It's very unusual for a lower caste son of a tea seller to become a senior politician, let alone prime minister. He's only the second lower caste Indian prime minister ever. So he had this background in the kind of Hindu religious right. And that is part of what makes him popular. He appeals very much to constituency in India which believes in Hindu nationalism. He is a Hindu nationalist.

On the other hand he also believes in economic development and these are the two, to some degree contradictor, parts of his belief system. In a sense it's a bit like the Republican Party in America – you have the Christian right and the pro-business people. Modi has a similar coalition that he has to try to keep on board – the cultural and religious conservatives, and more pro-business types. It's a balance as to which of these is going to be in the lead.

It tells you something about India that at the moment, Modi isn't seen as an extremist anymore, because the Hindu right has moved even farther to the right.

When he was elected, there was anxiety about what it might mean for communal tension. Has that been borne out?

Modi is unpopular amongst the extremes of the Hindu nationalist right because he's not carrying out enough of their agenda - rewriting textbooks, changing the law so that Hindus are recognised as the primary group in Indian society, particularly to the detriment of Muslims. At its most extreme there is a Hindu chauvinist tradition that is analogous to Islamism, although it doesn't tend to be violent in the same way. Modi arose in an earlier variant of that tradition, but he has since moderated, at least to the extent that it's in abeyance because he also believes in the church of economic development.

But I think it's clear that Hindu nationalism is gaining in strength in India and secularism is almost a defeated force. It's not impossible that it may be revived, but the old secularist tradition is in a pretty weakened state. That is also wrapped up in the broader story of globalisation. India has been globalised. This has caused economic prosperity, it has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, but it has also created a world that is alien and confusing, a world in which women are entering the workforce in a traditionally patriarchal society, in which people who previously didn't have money suddenly do. In those circumstances, people often seek solace in traditional identities, and therefore you've seen this upswing in people interested in the heritage of Hinduism. Some take that to an extremist point of view.

Is there a risk of increased authoritarianism in India?

I think Modi is likely to win a second term in 2019, but is unlikely to win such a strong majority as he did last time - he won a hugely unusual majority. In that sense, the odds of him becoming a kind of Erdogan figure lessens. I don't think this is likely but the nightmare scenario is that Modi or the person who comes after him decides to follow a more overtly anti-democratic path. There certainly are a lot of liberals in India who worry about mirroring Turkey or Hungary. That is more to do with the health of the country's liberal institutions. The court system is in a great mess. Many of the institutions that you would look to protect liberal rights do not appear to be doing so. In addition to the fear that Modi himself may have a populist authoritarian tinge, there is a worry about the state of India's constitutional apparatus and its ability to protect minorities in particular.