Biotechnology is more advanced than ever. From next-generation prenatal tests to genome-editing, today we have unprecedented power to predict and shape future people, raising questions about who we count as human and what it means to belong. How will can square new biotech advances with the real but fragile gains for people with disabilities - especially when their voices are often absent from the conversation? In his new book "Fables and Futures: Biotechnology, Disability, and the Stories we Tell Ourselves" (MIT Press), George Estreich - poet, memoirist, and father of a young woman with Down syndrome - explores the place of disability in our narratives of technology. Here, he discusses his ideas.

What drew you to this subject matter?

As is often the case with writers, one book leads to another. Fables and Futures grew out of my last book, The Shape of the Eye, a memoir about raising a daughter with Down syndrome. Writing that book, I came to see that I couldn’t just tell Laura’s story; I had to reckon with the stories told about her condition. Fables and Futures extends that exploration, thinking about our broad, unending conversation about biotech and disability - the stories we’re telling ourselves now. I spend part of the book dissecting those stories, looking for patterns, and part of the book telling new ones, mainly about me and Laura. So this book continues and builds on the last one.

In what ways do we misunderstand disability?

A very big question, and one that the field of disability studies will always be answering. But I’ll focus on a few things I’ve learned from other writers, disabled and nondisabled, who’ve explored this question before me. I think we often tend to automatically equate disability with suffering or tragedy. Other closely related problems include understanding disability in terms of disease, abnormality, or defect; seeing disability as a purely measurable and physical phenomenon, like an extra chromosome or a visual impairment; and seeing a disability as the most relevant fact about a person, not as something whose meaning changes in, is created by, context. This is not to deny the real difficulties physical differences can entail. But too often, the lived complexities of disability tend to get elided, and the voices of people with disabilities tend to get ignored. It also means that in some cases - notably Down syndrome - stereotypes about personality traits prevent us from seeing, and listening to, the individuals who have the condition in question.

What troubles you about the meeting of biotech and disability?

I’m not troubled by that convergence per se. There are many ways in which biotechnology can be a direct or indirect benefit to people with disabilities. To be disabled is not necessarily to be sick, so to the extent that biotech developments can help anyone, they can help people with disabilities too; and to the extent that tools like CRISPR speed basic research, they will likely have indirect benefits that filter to all of us. In a more utopian vein, it’s possible to imagine a world in which biotechnology is mainly focused on helping people flourish, whoever they are, as opposed to preventing or altering conditions deemed abnormal.

But in the world we actually live in, the negative features of disability tend to get emphasised in order to boost the fortunes of a particular technology. Advocates for CRISPR, for example, may suggest that a laundry list of conditions can be cured or averted. When that list is heterogeneous - for example, including schizophrenia, autism, deafness, dwarfism, and cancer - the tendency is for all of them to sound like abnormalities, bad things. The diseases are ballast for the disabilities, even when many people with the conditions in question do not see themselves as sick. Because I don’t identify as disabled, I’ve quoted other writers throughout the book who can speak to the experience of disability, including people with Down syndrome.

How are stories used in the promotion of new technologies?

In many ways: stories about and by charismatic scientists (in memoirs, feature articles, and TED talks); stories of parents and families making successful use of technology; promissory and speculative stories, forecasting everything from the revival of extinct species, to choosing desired qualities of children, to the elimination of disease. Beneath the individual stories is a basic progress narrative, in which science and technology bring us a better world.

I wanted to break down the story, to reduce it to its components, to look for patterns. One instance is the way technology is named, the way the ordinary name for a technology is already persuasive: “noninvasive” prenatal testing (NIPT), for example, or “mitochondrial therapy.” Though these are neutral-sounding labels, they’re actually persuasive, chosen for a purpose; the name “noninvasive,” for example, anchors a consistent marketing message, in which NIPT is opposed to “invasive” tests, such as amniocentesis.

But stories are built up from characters too. In popular discussions of biotechnology, the same characters recur: the scientist, the Luddite, the “designer baby.” I’m interested in the way those characters are deployed. At the same time, I’m interested in the people left out of the story, or understood purely in terms of risk. Who gets a story, who gets to tell one, and whose stories are credited.

You write about echoes of eugenics in current discussion of genomes. Could you expand?

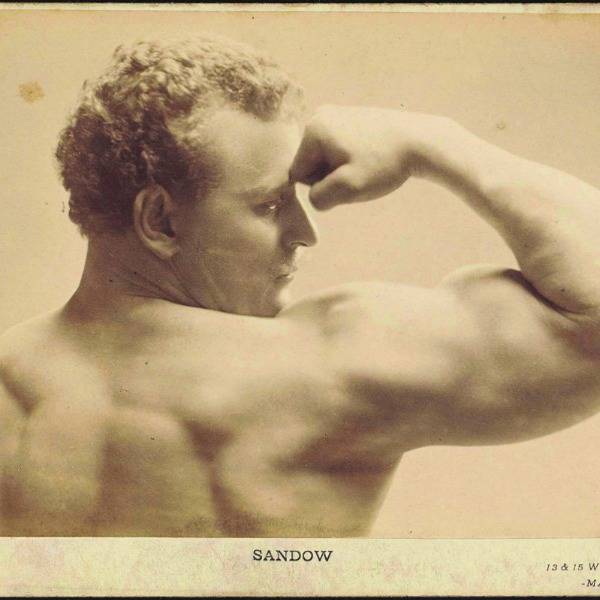

It’s been nearly a century since the high tide of American eugenics, with its visions of breeding the “best” Americans for the good of the gene pool, and of sterilising the unfit. It’s critical to emphasise how far we have come, not least in our understanding of the basis of human heredity.

That said, historians like Nathaniel Comfort, Alexandra Minna Stern, and others have documented the continuities between the mainline era of eugenics and the present day. The context is radically different, but the idea of directed evolution is still around, and many themes persist. Among these are images of ideal families and children; the understanding of disability as a cost to society; the idealisation of intellect, and the avoidance of intellectual disability; and the existence of persuasion itself, a rhetoric that joins literary tactics to scientific authority. That rhetoric, both a century ago and today, is pervaded by metaphors of disability: rational control is opposed to “blind” nature.

You say that biotech raises questions about what kind of people we value. In what way?

Which biotechnologies we develop, which are profitable, which we sell, how we sell them: all reflect our assumptions about which sorts of bodies and minds we value, and which sorts we would collectively prefer to avoid or cure.

Fables and Futures begins with an epigraph: “Technology is neither good or bad, but it is never neutral.” It’s impossible to say that “biotechnology” is good or bad: like everything else - including disability itself - its meaning depends on context. But of course, biotechnology is part of that context, and it works in unpredictable ways. The ability to detect a condition prenatally can be at once useful and necessary in some cases, while contributing to stigma in others: for example, the very fact that a condition is avoidable means that parents can be considered morally obligated to avoid it (or blamed for failing to avoid it).

When you look at biomedical developments, are you optimistic?

Biomedicine is too vast, and the future too uncertain, for me to predict much, even to be optimistic or pessimistic. I see a great tension between the ideas of belonging and improvement, between an understanding of disability as a social and political identity, on the one hand, and as defect and abnormality on the other.

I do see a rapid movement towards the adoption of germline editing, which concerns me: even in the last few years, the consensus seems to be that germline editing is both desirable (as long as it’s safe) and inevitable. I think that a far broader and deeper conversation is required before we take this step as a species, and I think that conversation needs to include all of us, including people whose disabling conditions are invoked in support of the project. Understanding the way the conversation works now, the persuasion both subtle and less so, can help us to engage more fully with the issues involved.