This article is a preview from the Spring 2019 edition of New Humanist

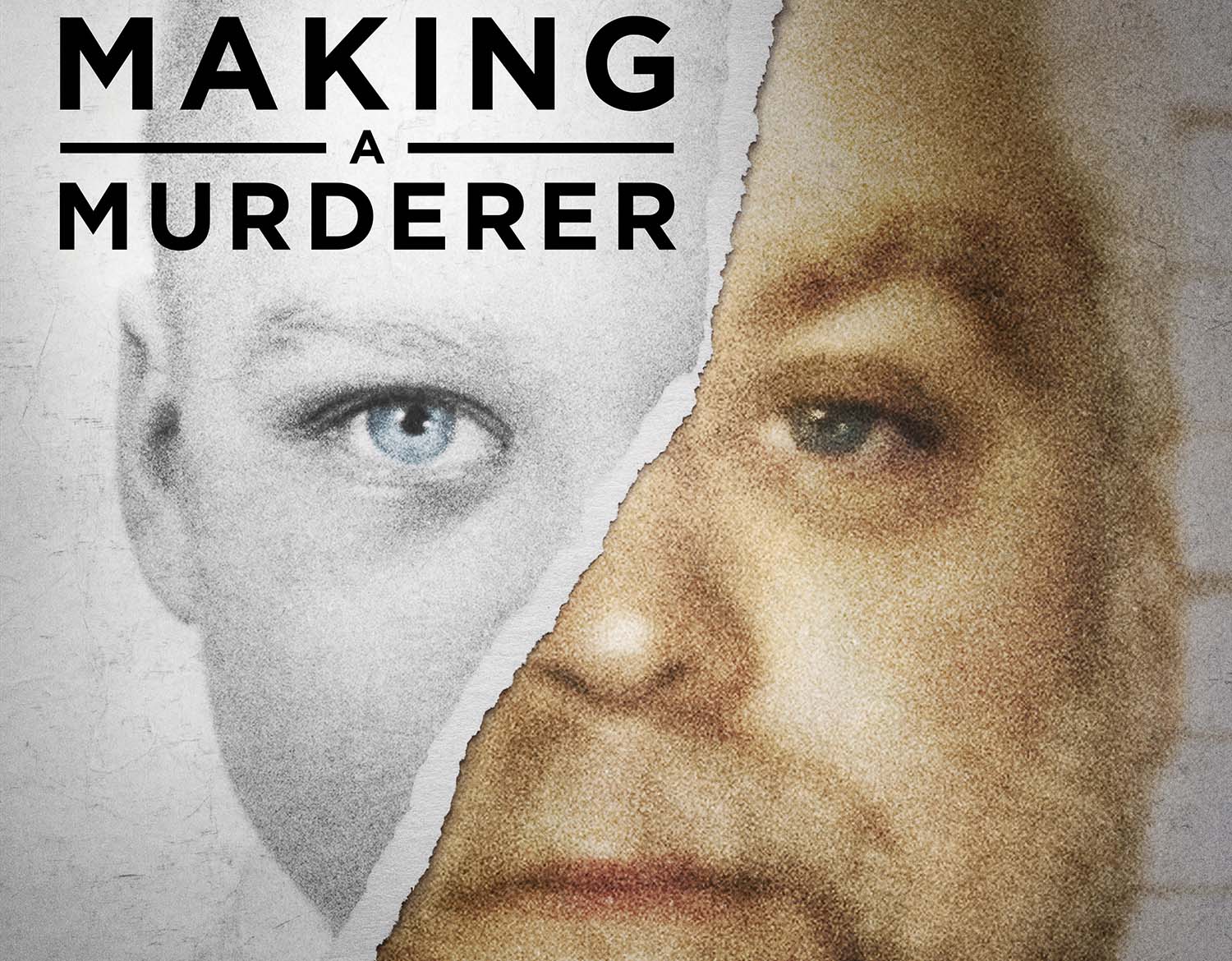

The story of Steven Avery, the subject of the popular Netflix true crime documentary series Making a Murderer, is deeply tragic. The 56-year-old salvage yard worker from Wisconsin, USA, was convicted of sexual assault and attempted murder in 1985. He had served 18 years of his 20-year prison sentence when new DNA evidence emerged that exonerated him of these crimes. He was released in 2003 and widely recognised as a victim of police misconduct. Just two years later, he was arrested again and charged with a completely different murder. In 2007 he was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. Repeated appeals and applications for a new trial have failed, and he remains incarcerated.

The first series, released in December 2015, was watched by over 20 million people. Avery became a kind of folk hero, the subject of dozens of spin-off campaigns, videos, podcasts and articles. Unusually in the age of streaming television, when viewers watch on their own schedule, the question of his innocence or guilt became an old-fashioned water cooler topic, with office workers and radio phone-ins buzzing with opinions. Wannabe investigators congregated on forums like Reddit to share interpretations of DNA evidence and CCTV footage.

Although interest in true crime was already high at the time of its release – the first series of the hit podcast Serial had come out in October 2014 and HBO’s The Jinx was released in February 2015 – it was the first season of Making a Murderer that took it to a new level. All of these series, and the dozens that have followed them since, take a murder case and repackage it as entertainment. More than that, these are prestige productions, with large budgets, original music and the kind of camera work that indicates “highbrow” subject matter.

It’s easy to get caught up in the compelling sort of narrative they offer: perhaps if we binge just one more episode tonight we will find out who really did it. This effect can be so potent that sometimes it’s difficult to stop and think critically about what we are watching. A larger question is prompted by the recent boom in expensive, prestige true crime productions. Is it ethical to consume stories of murder, rape and miscarriages of justice as if they existed just for our entertainment?

The popularity of true crime stories goes back much further than the advent of streaming services. From the beginning of widespread newspaper distribution in the late 17th century, reports of grisly murders and violent attacks were a big part of how proprietors shifted copies. As police forces came into being in the 19th century, interest in the way crimes were investigated and solved grew. Cases like that of Constance Kent, convicted of murdering her four-year-old step brother in Wiltshire in 1865 after a police investigation and a religious confession, sent the British press and public into a frenzy. Novels like Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone, from 1868, incorporated elements of real life cases, breeding further interest.

Whether it comes via reading about Jack the Ripper in the 1880s, tucking into Vincent Bugliosi’s account of the Manson murders in the 1970s or downloading an episode of Serial in the 2010s, the impulse to revel in the details of others’ misfortunes remains the same. There’s a cosy sense of self-preservation and congratulation contained in consuming these stories – rather them than us, our subconscious says, as we dive into the horrors of the next chapter or episode. Crime in fiction is such a popular genre and its narrative structures are so familiar that the desire for similar stories easily carries over into real life reports.

During the 20th century, specialist magazines such as True Detective emerged, which frequently carried front covers emblazoned with headlines like “The Nylon Strangler”, “Corpse at the Picnic” and “The Slasher and the Young Widow”. These publications focused particularly on tales of murdered women, always treading the line between horror and sexual titillation. There was never a sense that this was intellectual entertainment, though. For decades, cheap magazines and tabloid newspapers were the natural home of these stories.

This gritty sensibility remained through much of the 1990s and 2000s. People continued to enjoy true crime, but they probably wouldn’t eagerly share their passion for it in public. These were magazines to be flipped through in a waiting room, or television shows like Dateline or Crimewatch to be consumed at home with a TV dinner. There was a sense that overtly taking pleasure in such horror was not something to be proud of.

The advent of glossy, big budget series like The Jinx and Making a Murderer changed the status of true crime. They appeared on premium TV services like Netflix and HBO, and were advertised with huge billboard campaigns. The internet and social media allowed fans to connect with each other and share theories, and suddenly “enjoying podcasts about murders” was something people were more than willing to share about themselves. A whole support system sprang up around this newly public fandom, too – the podcast My Favourite Murder, in which two comedians discuss the gruesome cases that most appeal to them, has hundreds of thousands of listeners and has just begun releasing its own spin-off shows.

The way these prestige true crime TV series were filmed hinted at more complex, almost arthouse cinematography, with unusual angles and aerial tracking shots. Rather than focusing just on the grisly interaction between victim and murderer or the police investigation (although both are still present), they shifted the emphasis onto a character that stands in for the audience. In Making a Murderer, this is the filmmakers Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos, who made the first series over a period of ten years. In the podcast Serial, host Sarah Koenig makes explicit that the listener is hearing her own subjective view of the case – after all, much of it is delivered in her own voice.

The grammar and style of these series are so recognisable that they have spawned dozens of imitators and parodies. One of them, American Vandal, is so pitch-perfect in its observations – right down to the aerial shots and the slash of paint across the suspect’s eyes like the Making a Murderer poster – that it almost feels bad to laugh. That is, until you grasp that it is a mockumentary about an unknown “vandal” who spray-painted penises on some cars. Somehow watching it is a relief, because its relentless silliness makes the deadly serious tropes of the shows it is parodying seem less grave and more absurd.

In October 2018, Making a Murderer returned for a second series. There were no new substantive new developments to report in Avery’s case, or indeed much of a public interest argument for airing extended interviews with his family and friends. But the show is a major draw for Netflix, so it’s not difficult to understand why more episodes were made – true crime is big business.

The narrative that today’s true crime sells about itself is all about exposing miscarriages of justice – this isn’t voyeuristic, intrusive or harmful, it seems to say, but an important social affairs issue that you are assisting with correcting somehow by gulping down episode after episode. Many of the themes it explores, such as toxic masculinity, racism and class prejudice, are vital issues that deserve more coverage and attention. Packaged as a subplot in a neat whodunnit, though, these subjects lose their potency.

True crime tries to make us feel good for watching it, virtuous even, in a way that the penny dreadfuls or cheap magazines of decades before never did. Yet watching the new episodes of Making a Murderer, I felt uncomfortable. Who really benefits from our obsessive viewing of TV shows about other people’s misery? It is certainly not the original victims of these crimes.