This article is a preview from the Autumn 2019 edition of New Humanist

In 1978 David Goodman, a writer for The Futurist magazine, identified 137 predictions in George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984. He concluded that at least 100 of them had already come true. Six years later, the same magazine ran an editorial that claimed, “As a forecaster of the actual world of 1984, Orwell is so wrong as to be drummed out of the company of forecasters.”

If this seems like a wild shift from one end of the spectrum to the other, then you’ll be happy to know that polarised views on the book – its predictions, accuracy or originality – are nothing new. Since its publication 70 years ago, the way 1984 is discussed often reveals much about the current political climate. These days, we seem to have swung back to treating the book like a crystal ball.

After the election of Donald Trump, the novel’s sales rocketed and it once again became a best-seller. Was Trump’s manipulation of the truth – his grandstanding on social media and his cry of “fake news” – evidence that we now lived in a 1984 world? Wasn’t the term “Orwellian” introduced to describe precisely these situations?

With this renewed prominence, two questions about 1984 come to mind: who does it belong to? And what about Orwell the man? Because in the years since the novel was first published, our understanding of both has become more convoluted than ever. Both left and right claim George Orwell – the pen name of Eric Blair, a prolific political writer, socialist and critic of empire who wasn’t afraid to change his opinion; an idealistic Spanish civil war volunteer and, later, a committed anti-Communist – for their own causes.

The alt-right youth network Turning Point, for example, loves to use Orwell quotes in its tweets. Neoconservatives and reactionaries wield the term “thought police” against what they see as the “politically correct” left. From the other side, there have been a number of pieces like “Reclaiming Comrade Orwell” in the fashionable US leftist magazine Jacobin that take note of this trend and attempt to counter it.

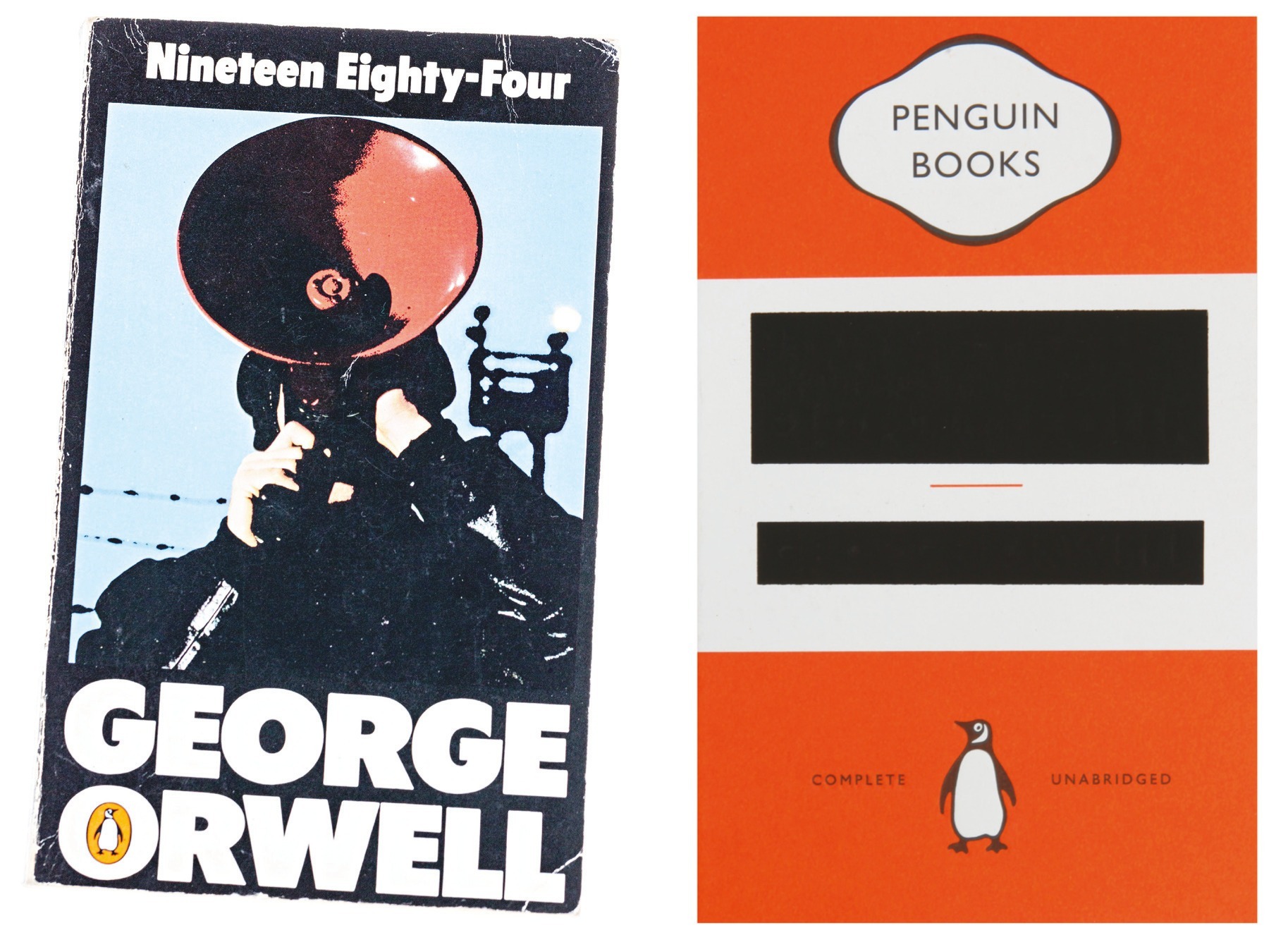

In The Ministry of Truth, a new “biography” of Orwell’s best-known novel, the journalist Dorian Lynskey attempts to make sense of this complex history. By extension, he brings us an account of Orwell not only as an author and a cultural phenomenon, but a person living through hard and uncertain times as he strove to maintain clarity and perspective.

The book retells the events in Orwell’s short life (he died when he was only 46, after a long battle with tuberculosis) that led up to the publication of 1984, and traces the varying reactions to the book after publication. It also situates Orwell’s ideas within the intellectual web of the time, tracing the connections to his contemporaries, his reading and how these ended up influencing him.

Orwell is often hailed as a truth-teller, someone who was unafraid to see and comment on the reality of power. Yet those who seek to claim him for contemporary political ends frequently do so by resorting to “selective quotation which often verges on fraud”, as Lynskey puts it. In this muddled position, Orwell joins a long line of thinkers – Nietzsche comes to mind – whose words become the very ammunition through which they are misinterpreted, appropriated and even demonised.

Nevertheless, writes Lynskey, “1984 remains the book we turn to, when truth is mutilated, language is distorted, power is abused, and we want to know how bad things can get.” With smart and refreshing prose, Lynskey builds a case to help us see through such modern attempts to misappropriate the author – like, for instance, when Orwell’s words found their way into the mouth of the far-right broadcaster and conspiracy theorist Alex Jones.

Orwell was clear on pretty much every subject he tackled. He was a trenchant critic of unchecked state power, along with the rhetorical manipulation that accompanies it. These views were shaped by his experience of how the USSR-backed Communists crushed all dissent on their own side in the Spanish civil war. He had no time for those on the left whom he saw as apologists for Stalin’s regime, and wrote that Communism had become “a form of socialism that makes mental honesty impossible”.

Yet to counter those who would use this to claim Orwell for the right, he saw an equal danger in free-market capitalism. In a review of Friedrich Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, a book that influenced the architects of the neoliberal economic consensus that has dominated western politics in recent decades, he warned that Hayek’s free-market fundamentalism would mean “a tyranny probably worse, because more irresponsible, than that of the State”. That leaves little room for doubt as to his political leanings, even if it is often overlooked. “I find it necessary to remind people I’m actually a socialist,” as Orwell wrote.

It was honesty that Orwell prized above all. In his fight against lazy thinking, he spent a lifetime dissecting not only the dishonesty and contradictions of others, but also his own. This is where our contemporary treatment of his work does an even greater disservice.

Because of Orwell’s elevated status in our culture, and the simplifications that entails, it’s become too easy to dismiss him as clichéd, or to mistake the reactionary interpretations of his work for the content of the work itself. But it’s worth considering how this came about, and how his views progressed over the years. Perhaps the most important thing to appreciate, more than his specific political arguments, is that Orwell practised a form of what we might now call “radical honesty”.

The Ministry of Truth uses one novel to take in almost three quarters of a century. The end result is not a rehabilitation of Orwell so much as a re-humanisation of the man, removing him from the hands of those who would place him on an altar or use his words for their own devices. Since we now live in a time when the words and ideas of too many writers, artists and philosophers are twisted and used to mislead us, it’s heartening to see that we can still salvage at least part of the truth.

“The Ministry of Truth” is published by Picador