This article is a preview from the Winter 2019 edition of New Humanist

Sometimes people change their minds while under the kind of pressure that could give you the bends. I’ve spent the last two years interviewing people who did just that. Like Susie, who discovered her husband had been telling a criminal lie since he was 12 years old and began to fear for herself and her young child. Or Peter, who opened his ailing mother’s post for her and discovered she wasn’t who he’d thought she was. Or Dylan, who quit the strict apocalypse-heralding religious sect he’d been raised in. Sometimes their stories were about not knowing what to believe, like when upper-class Alex finished a stint on the reality TV program Faking It, where he had been trained as an East End bouncer, only to realise he didn’t know which of his identities he’d been faking. Or Nicole, who spent years believing her mother abused her until she read an exposé arguing the whole thing had been a setup.

I had wanted to know what really goes on when someone changes their mind. The project started just after I finished a piece for the US radio show This American Life. The conceit had been simple: turn around to my own catcallers and try to reason them out of doing it. Every one of the men I spoke to said they thought women enjoyed it. I thought, because I used to think I understood persuasion, that I could just tell them, “We don’t”. But after hours of conversation these men walked away as sure as they’d ever been that it was okay to grab, yell at or follow women on the street.

So I wanted to know: what cogs are turning when mind-changing goes right? And can it tell us anything about our own attempts at persuasion?

It’s easy to think we know what a good change of mind is. We think we know what rationality requires, and the only question is why other people don’t do it more often. The ideal mind-change is calm. It reacts to reasoned argument. It responds to facts, not to our sense of self or the people around us. It resists the siren song of emotion. In the technological belt of California, where the only thing more precisely engineered than the software is the people – or maybe the people’s teeth – there is a whole organisation dedicated to achieving this ideal. It is called the Centre for Applied Rationality, and it will sell you a $3,900 four-day workshop during which participants eat, sleep and do nine hours of back-to-back reason-honing activities together daily under one (presumably rationally designed) roof. The proper way to reason, at least according to our present ideal, is to discard ego and emotion and step into a kind of disinfected argumentative operating theatre where the sealed air-conditioning vents stop any everyday fluff floating down and infecting the sterilised truth.

* * *

People like to talk about the “public sphere” – if there is such a thing then its convex edge reflects this image back at us. Think of the number of programmes dedicated to the mind-changing magic of two sides saying opposite things. The branding of these things often bakes in a little reward: how brave I am, for attending the Festival of Dangerous Ideas; how clever, for my subscription to the Intelligence Squared debates.

But how many times have you seen a TV panel discussion in which the defender of one view turned to their opponent and said, “You know, actually, that’s a pretty good point”? Ever? And if the ideal doesn’t work in practice, what makes us so confident that it’s the ideal?

While researching and speaking to people who really had changed their minds in high-stakes ways, I was routinely struck by how personal and idiosyncratic their routes to truth had been. For Dylan, for instance, the decision to leave his cult had almost nothing to do with what he believed. Instead it was about who he believed. After years of being married, he discovered that his wife had all along been concealing from him that she, privately, did not believe what the cult did – she never had. She had married him and loved him but had all along hoped that he would one day change his mind about whether the apocalypse was really coming. He trusted his wife more than his elders, and so this, rather than any countervailing evidence, finally uprooted his 26-year-long beliefs.

Or take Alex from Faking It, whose path to changing his mind about who he “really” was had very little to do with evidence or argument in any traditional sense, and much more to do with marshalling the same evidence into a different story. Alex, like most of us, had fallen into a kind of evidentiary loop about his own personality: his belief that he had certain traits led him to enact those traits, and thus his beliefs created the evidence that in turn supported those beliefs and so on, ouroboros-style. The way out of this loop was not more evidence, it was to momentarily let go of the hope that evidence about ourselves can be marshalled into a coherent personal autobiography with the self as the unified narrator. Or Nicole, who has spent years wondering whether her own memory of being abused as a child is accurate. What weighs on her in her uncertainty is not just the evidence and the arguments, but the costs of being wrong if she finally does settle on one verdict. Over and over, I heard stories of people finding their way back to the truth by using trust, their sense of self, hope, the things that other people told them: all the things we typically think we should check at the door when we’re trying to be rational.

But it’s not clear that these strategies are, in fact, irrational. Philosophers and scholars of rationality have spent millennia asking the same question I did moments ago: what makes us so sure we know what rationality requires? Maybe you think it’s simple, that being reasonable just means believing things in proportion to the evidence, but if that was your first thought then please accept my condolences as you plummet backwards down the rabbit hole. What counts as evidence? Are sensory perceptions evidence? Or feelings, like empathy? If not, what licenses your belief that other people’s suffering matters? When is there enough evidence to believe something? Do different beliefs require different amounts of evidence and, if so, what sets them apart? Could anything else have a bearing on what we should believe, like the costs of error? And what sort of “should” are we using when we ask, “What should we believe?” Are we aiming at truth, or at morality, or are they the same goal? Are the standards for believing mathematical or scientific truths different from moral or interpersonal ones, or is there no distinction? What’s the responsible way to respond to the news that someone as intelligent as you, in possession of as much evidence as you, reaches a different conclusion?

* * *

Over millennia these questions about what to believe, when, and why, have pinballed back and forth between the most blisteringly intelligent people of their day, and still nobody has the settled answers. Not all that long ago, on philosophy’s timescale, the Pittsburgh-based philosopher John McDowell wrote his seminal work Mind and World, which wonders among other things what sort of thing rationality could be. Reviewing it, Jerry Fodor wrote that “we’re very close to the edge of what we know how to talk about at all sensibly”.

I do not have the poetic instincts or vocabulary to be able to describe, against that backdrop, what hair-tearing frustration it is to see the concept of “rationality” bandied about in public without any acknowledgment of the longevity and complexity of these questions. Instead, pundits who take themselves to be the chief executors of rationality simply assert things about what it is to “be reasonable” by taking as bedrock the very things that still remain to be proved.

You will see people speak as though “being reasonable” is just being unemotional, as the MP Michael Gove did when he appeared on Good Morning Britain after the fire in Grenfell Tower, speaking in tones usually reserved for children who’ve had too much sugar. “We can put victims first [by] responding with calmness,” he told Piers Morgan. “It doesn’t help anyone, understandable though it is, to let emotion cloud reason . . . And you, [Piers], have a responsibility to look coolly at this situation.”

The idea seems to be that being emotional precludes being rational, and we can select only one way of being at a time. Antonin Scalia, the former US Supreme Court Judge, argued along these lines when he wrote, “Good judges pride themselves on the rationality of their rulings and the suppression of their personal proclivities, including most especially their emotions . . . overt appeal to emotion is likely to be regarded as an insult. (‘What does this lawyer think I am, an impressionable juror?’).” Where did we get this confidence that emotion has no place in reasoning?

Or you will see people speak as though “being rational” is just the task of getting your behaviour to match your goals, an inheritance from an economic model of the rational consumer. You want to save more money? Here’s an app. You want to exercise more? Here’s a morning routine. Geoff Sayre-McCord, an impossibly genial philosopher at the University of Chapel Hill in North Carolina, who collects motorcycles and writes about belief, told a story at a Princeton workshop on the ethics of belief that illustrates how slippery this idea of “rationality” can be. An economist friend of his gives a speech at a conference, espousing the idea that “rationality” governs the space between our goals and how we act, but has nothing much to say about which goals we should pursue. Hours later, at the pub, the economist laments his teenage son’s failure to set the “proper” goals: “All he does is play drums and drive around with his friends! He doesn’t study; he doesn’t think about his future. He’s being so irrational.”

In our haste to congratulate ourselves for being reasonable, we accidentally untied the very notion of “rationality” from its rich philosophical ancestry and from the complexity of actual human minds, and now the idea of “being reasonable” that underpins our public discourse has little to do with helping us find our way back to the truth, or to each other, and altogether more to do with selling us a dream of an optimised future where everything is protein powder and nothing hurts. The strange thing is that most of us are already suspicious of this image of “rational debate”. Most of us learned long ago that changing our minds about something that matters – whether we were right to act the way we did, whether to believe what we are being told, whether we are in love – is far messier than any topiaried argument will allow. Those spaces aren’t debates. They are moments between people – messy, flawed, baggage-carrying people – and our words have to navigate a space where old hurt and concealed fears and calcified beliefs hang stretched between us like spun sugar, only catching the light for a second or two before floating out of view again.

* * *

So why, when we know that changing our minds is as tangled and difficult and messy as we are, do we stay so welded to the thought that sterilised debate is the best way to go about it? Why do we hold our ideal of rationality fixed and try to bend ourselves around it, instead of the other way around? Why do we still think the important question is a psychological one about how we do change our minds, instead of a philosophical one about how we should?

In each of the stories I encountered in my research, one thing was consistent: without an intimate genealogy of a person’s beliefs, it was close to impossible to predict how they might change their mind – and how they would cope with the fallout. I think it is a service to our current persuasive crisis to return some of our attention to individual success stories. We are already agonisingly familiar with the ways persuasion can go wrong. My hope is that returning to the intricacies of how it goes right might provide us with a useful blueprint for some of our most difficult persuasive missions. When we set out to change people’s views it’s easy to forget just how resistant minds are to changing. It’s easy to feel, as I did when I spoke to my catcallers, like we’ve spent a whole lot of conversational energy ticking all the boxes in the rational persuasion manual and been rewarded with nothing but a frustrating stalemate. It is a uniquely teeth-grinding moment: not just to fail to persuade, but to have no idea what went wrong. My hope is that in paying attention to the mechanics of individual stories we can learn to better diagnose these moments, and, more optimistically, to see what happens when things do click. The people in these stories pulled off massive mind changes using altogether human tools of reasoning like trust, and credibility, and their sense of self, and their emotions, and their ways of avoiding the shame of having to reckon with the fact that they were wrong. If we can understand those tools a little better, and see them as rational as well as practical, then we may be able to use them in changes of mind we most want to accomplish.

It strikes me as a tragedy that in deference to our rusted-on idea of persuasion, we structured our public discourse around regimented debates, leaving persuasive strategies built on how we actually think to the used-car salespeople of the cognitive landscape: advertising executives, or lawyers, or actual used-car salespeople, whose highest aspiration for their insights is that they might better crowbar purchases or decisions out of the unsuspecting public. It is as though beginning in the muddy reality of being a person was a fitting strategy for professions that never hoped to leave that muddy reality, but for professions whose highest aspiration was truth, enlightenment, reason or progress, the chaos of actual life was not just useless but distracting.

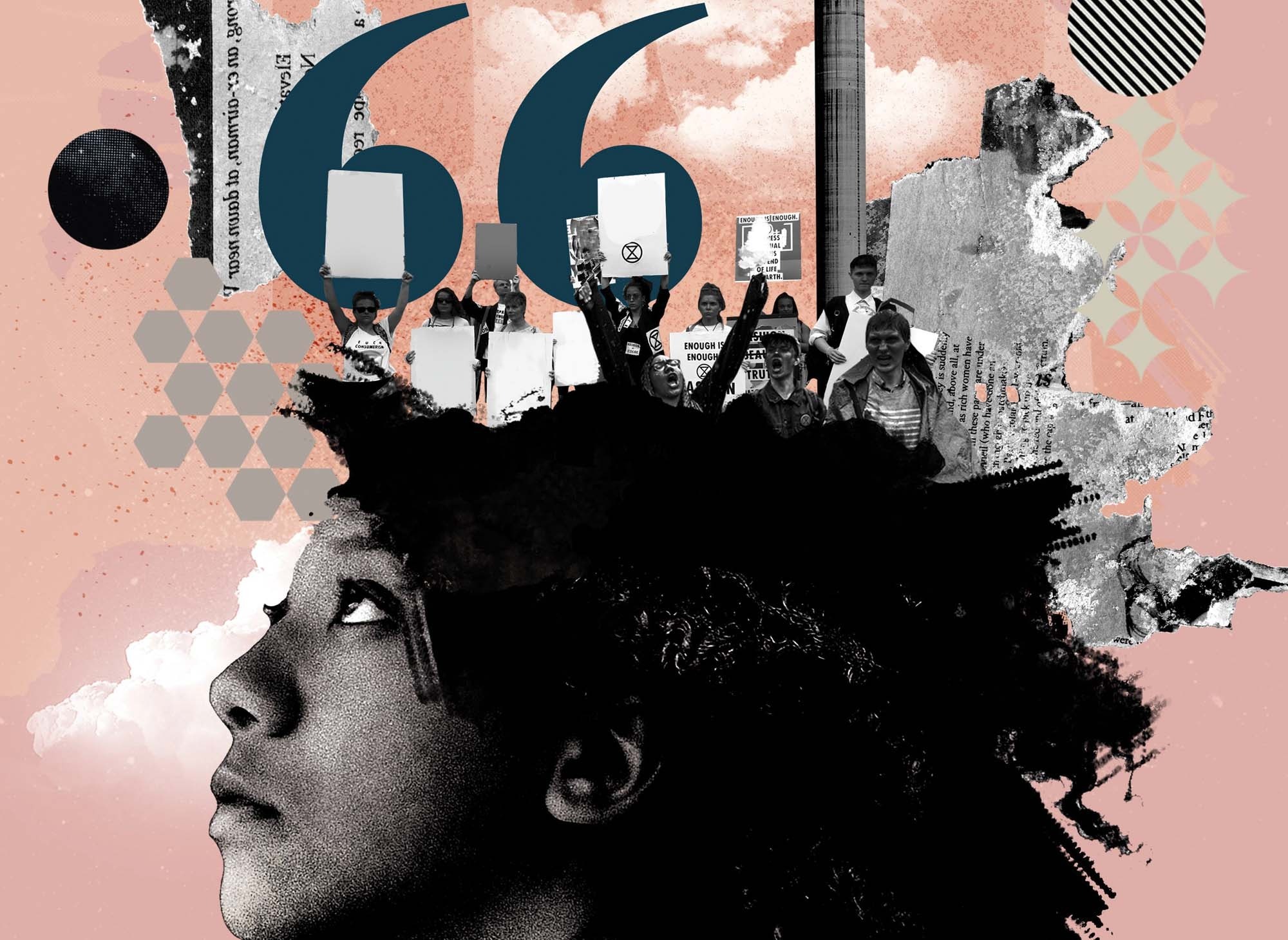

And so the people who trusted this model of rational discourse were advised to retreat from the messy and the real, declaring progressively more and more ways of connecting to the world or other people to have no place in a proper argument. Or they spent their time reading manuals about how to spot a fallacy and dutifully tuning into each new broadcast debate trying not to wonder why it feels so hollow. And now those of us who felt like we should have been the most useful warriors for persuasion sit suspended, alone, on syllogistic crags far above a world where Nazis are back, and so is polio; where it’s prohibitively expensive to fight either, and the oceans are rising while we tell each other to just “be reasonable”.

We live in times that demand a better understanding of persuasion. Perhaps it’s time to dial down our confidence in the sterilised TV debate, and turn our attention to real stories of what happens when we change our minds.