This article is a preview from the Spring 2020 edition of New Humanist

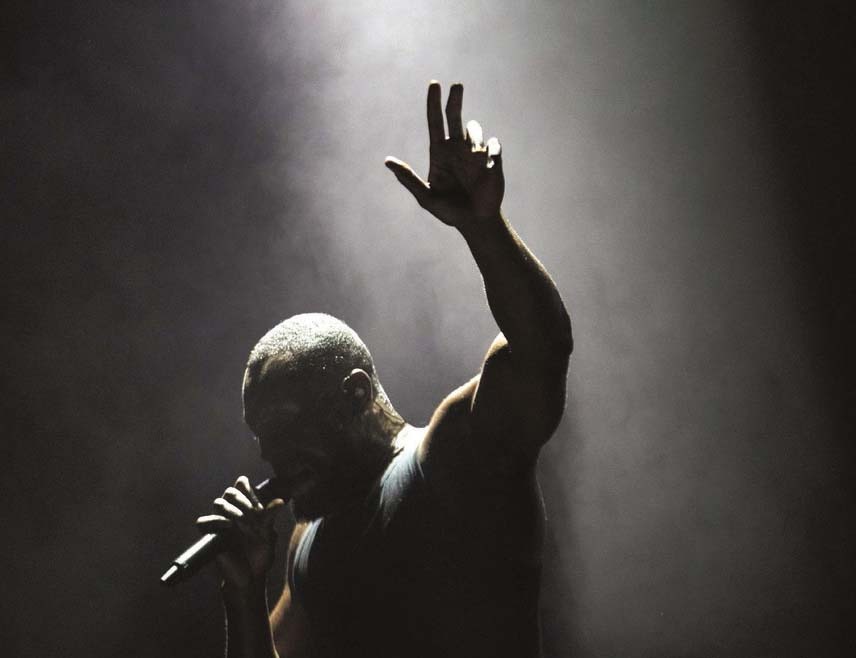

God is having a bit of a moment in British music. The BBC capped its Christmas Day coverage with a bible reading from Michael Ebenazer Kwadjo Omari Owuo Jr., better known as the chart-topping grime artist Stormzy. The Adidas-clad lad from South Norwood – whose stellar 2019 included a headline-grabbing set at Glastonbury, hit album Heavy Is the Head, the founding of a publishing imprint and the endowment of two scholarships at Cambridge – has made no secret of his religious beliefs. He proudly announces his attendance of the Word of Grace Ministries church in Kennington, south London, credits God for his success in interviews and garnishes his TV appearances with gospel choirs and churchy lighting effects.

Another hot musician, Femi Koleoso, the hyper-kinetic drummer of the up-and-coming London Afro-jazz band Ezra Collective, is similarly effusive in his praise for the Almighty. He recently took to Twitter to offer to pray for any of his fans who would appreciate him putting a good word in for them. Koleoso and Stormzy still have some way to go to match the devout lunacy of US rapper-producer and Trump cheerleader Kanye West – who went full gospel on his latest album Jesus Is King, and threatened to change his name to “Christian Genius Billionaire Kanye West” (was he serious? Who knows?) – but they have certainly brought religion back into generally profane pop.

Religious sentiment is hardly unknown in popular music. Boomers will recall Bob Dylan’s dalliance with the divine during his born-again phase in the late 1970s (though most Dylan fans will not welcome the reminder). It is widely known that Elvis was a great believer, but in the end none of his epic appetites – God, guns, burgers – could compete with his pious devotion to amphetamines. There were some tiresome moments during the explosion of rave culture in the late 80s when some new-agey ravers suggested that the DJ was God, or even, if the band Faithless are to be believed, that “God is a DJ”. Thankfully those drippy sentiments went out of fashion with the smiley face T-shirts. More plausible were the claims made by the Chicago house DJ Frankie Knuckles that he was a kind of high priest and his dancefloor a congregation. Knuckles grounded this claim in the fact that many of his black, gay crowd had been born and raised in the Church but exiled because of their sexuality. Knuckles’s club, the Warehouse in Chicago, offered them a route back into the spiritual communion denied them by Christian bigotry.

Black music has always had a deep and abiding connection to religiosity. The thread of spirituals and gospel is woven through all forms of black popular music, and the roots of soul, house and hip-hop are to be found in black American churches. Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Aretha Franklin and Nina Simone all had preacher parents; Sam Cooke, Ray Charles and Whitney Houston cut their musical teeth in the Pentecostal Church; and soul singer Al Green is himself Reverend, his career a continual oscillation between sacred and profane. The rapper Run, from the early hip-hop group Run DMC, is an ordained Pentecostal minister, and now styles himself Reverend Run.

* * *

As the great American sociologist Manning Marable told New Humanist in a 2009 interview, it is hardly a surprise that the Church has been the nurturing ground for black American music, because “the only social institution conceded to slaves was the Church, which therefore became the centre of black civic society, the haven in a heartless world. It was not only worship, but politics, welfare, concert hall and business.” It was as much a matter of necessity as of piety.

But the resurgence of religiosity in contemporary black British music follows different routes. In part it is a result of the reconfiguration of the black British urban population. Following migration from the colonies of the West Indies between 1948 and the late 60s – the much discussed and shamefully treated “Windrush generation” – black British culture was majority Caribbean. Migrants came from Barbados, Antigua, Trinidad and all the smaller Caribbean islands, but most of all from the largest island, Jamaica, bringing musical and religious traditions with them. The first generation of Afro-Caribbean migrants were almost all Christian, raised in conservative Protestant traditions initially imposed on the islands under colonisation but pretty much forgotten in the cities of the colonial “Mother Country”. Though majority-black churches were established throughout British cities, the British-born children and grandchildren of the Windrush generation found their spiritual nourishment outside the formal proceedings of the organised Church, often in the militant Old-Testament-plus-pan-Africanism of Rastafari reggae, with its own version of God – Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, dubbed Jah(weh) – and its own dreadlocked apostles such as Bob Marley, preaching peace, love and resistance to “Babylon”. This generation were far more at home in the sweaty congregations of the reggae soundsystem dance than the draughty pews of St Barnabas or St Jude.

Since the 1990s, the composition of the black British population has shifted, reflecting the influx of migrants from west Africa – Nigeria, Ghana and Sierra Leone – as well as east Africans from Somalia and Ethiopia. The African-heritage population of London now outnumbers the Afro-Caribbean. That influence can be seen across the landscape of black music culture. Many grime, pop and dance music producers are from African families,

including stars like Tinie Tempah, Koleoso and Stormzy. Whole new genres, like Afrobeats – a mash-up of hip-hop and West African highlife – have emerged as the soundtrack to this shift in black urban life. African migrants brought with them their religious affiliations too; in some cases this was Islam, but also a dizzying variety of Christian denominations and franchised evangelical ministries: the Trinity African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, Assemblies of God Pentecostal Church, and Stormzy’s own Word of Grace Ministries, which advertises itself as a church specifically for young people.

* * *

For students of British culture and music this is fascinating, but it poses a problem for the godless music fan. How much preaching are we prepared to accept in our pop? Do we want faith mixed up with our funk, God in our grime, Jesus in our jazz? I suggest the best place to ponder this question might be a church: specifically St James the Great in Clapton, east London. Since 2016, this Grade II-listed mid-Victorian church has been hosting the Church of Sound, a grassroots concert series showcasing the finest in funk, soul and new jazz.

Several times a month the pews are crammed with a distinctly secular mix of hipsters and multiculti-music aficionados there to see players like Fela Kuti’s drummer Tony Allen, the American underground jazz mavens Makaya McCraven and Jaime Branch, and the new generation of London talent like Moses Boyd and Femi Koleoso’s own Ezra Collective. The shows have a strong flavour of devotion; but really the strength of your religious conviction doesn’t matter, because it is the transcendent quality of the music that dominates.

Koleoso may believe his inspiring drumming comes from God; you, by contrast, may credit talent plus hard graft. So what? When the music is sublime and the crowd and players work in sync to produce a sense of rapture, questions of the facticity of revelation seem vulgar and beside the point. After all, as materialists we know that music is really just longitudinal waves causing particles to vibrate at different frequencies, but that hardly captures the miraculous effects of a baritone sax solo, or the soul-stretching capacities of a Koleoso drum break. In music, as in life, we need to get along with those whose explanation of the world is different, even opposite, to our own. We can find common ground in the seemingly endless ways in which simple vibration can move us.