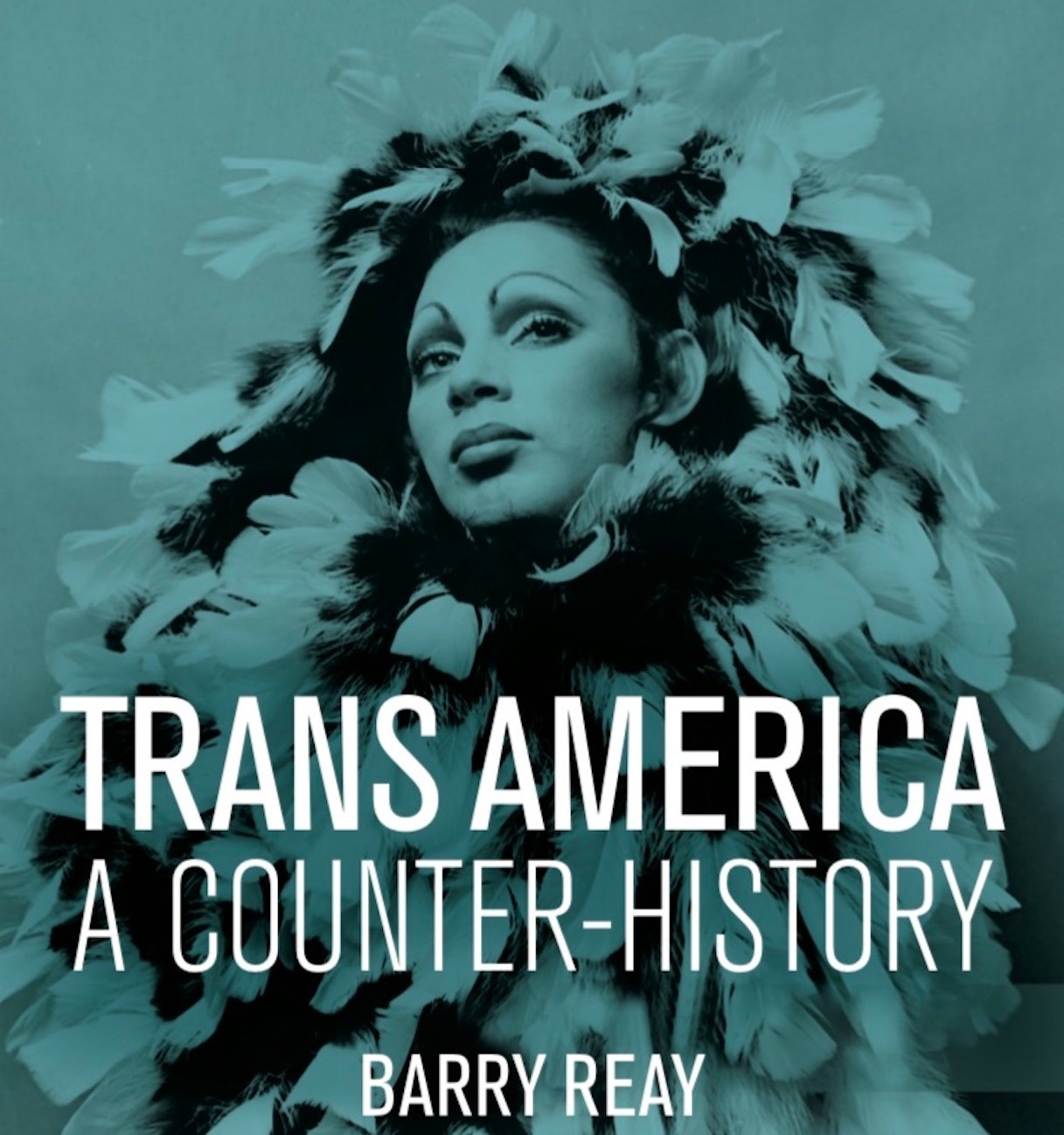

Barry Reay, Professor Emeritus at the University of Auckland, works on the history of sex and gender. His latest book, "Trans America: A Counter History", explores the rich and varied past and present of transness, from its pre-history in the nineteenth century to the transsexual moment of the 1960s and 1970s, the transgender turn of the 1990s and the so-called tipping point of current culture.

When did trans history begin?

Trans was first named – as ‘transexualis’ – in 1949. It then became more widely known as transsexuality in the 1960s and 1970s, transgender in the 1990s and more recently as trans or trans*. On the face of it, this is a short history. But of course trans has what could be termed a pre-history. Clearly there were people in the past who were ill-at-ease in their designated gender (the gender assigned at birth) and who strove to accommodate what we might today refer to as their true selves. In the period before the 1950s and 1960s, people did muse about their bodily configurations and the possibility of changing (or reconciling) them. There were those who were committed to presenting or living as the ‘other’ sex or who actually felt/knew that they were members of that sex. What complicates all of this is that these earlier trans tendencies, at least the ones in the nineteenth and earlier twentieth centuries, were usually identified as same-sex desires, as a type of homosexuality.

I started my story in the nineteenth century to demonstrate and explore this pre-history. However, I could have begun earlier. My essential point is the existence of this history: of feelings and tendencies before the naming of transsexuality and transgender (and trans) that cannot really be described as identities or fully formed subjectivities but which are, nevertheless, part of trans history.

What is the role of the fairy in what you call the “pre-history”?

When writing Trans America, it occurred to me that some of what could be termed trans before trans had been subsumed within gay history. The fairy, when mentioned, is part of a homosexual past. George Chauncey’s marvellous "Gay New York" (1994) springs immediately to mind, but I am equally culpable in my book "New York Hustlers" (2010). The effeminately presenting fairies and cross-dressers (the two are not the same) were ubiquitous in the big cities of the US in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. Their presence indicates that transness was not hidden away, but was part of a vibrant urban culture. The importance of the fairy (and cross-dresser) in trans history itself is that they demonstrate the range of transness in that period before transsexuality was named.

Who are some of the major figures included in the book, whose stories deserve wider recognition?

Lou Sullivan, a gay trans man in a period when gay trans men were rare, is quite well known but deserves greater acknowledgment for the messiness of his trans narrative and for his fascinating diary – which got me interested in the history of transgender in the first place. There are others whose stories and observations are woven into the fabric of "Trans America", who should be even better known: Juliet Jacques, Rae Spoon, and CN Lester, for example. There are important trans figures like Susan Stryker, who, more than anyone, has contributed to trans history as a researcher, theorist, and central participant.

There are also lots of minor figures in the book whose stories do indeed deserve wider recognition: Artie, the San Quentin inmate; the Oregon trans man Alan Hart; the fairy Jennie June, a self-described ‘girl without a vagina’; the gender-bending Cockettes; Patricia Morgan, a rather recalcitrant early transsexual patient; the cross-dressers of Casa Susanna; the female impersonators of New Orleans’s The Dew Drop Inn … There are so many trans stories.

You write about black working-class culture being “especially receptive” to gender and sexual flexibility.” How did this manifest?

I am not sure about why this was, but it was certainly manifest – and in Latino/a culture as well as in black communities. Some examples are the Harlem clubs and speakeasies of the 1920s and 1930s; the black female impersonators in Washington DC and Baltimore during the same period; the drag queens, drag balls, and female impersonation acts of the 1950s and 1960s; the club performers of the 1980s and 1990s and the New York trans street culture of the same decades, captured in the visual imagery of the photographers Jeff Cowan and Katsu Naito and the filmmaker Susanna Aiken, and in David Valentine’s anthropological work with the ‘Meat Market Girls’; house/ball culture in a variety of US cities in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, including the world of the famous documentary "Paris Is Burning" (1990/1); the black and Puerto Rican female masculinity of Daniel Peddle’s film "The Aggressives" (2005); and 21st century Los Angeles Studs. It is a rich and varied tapestry, demonstrating that the history of trans is much wider than the history of transsexuality.

What can we learn today from the backlash against the rise in trans visibility in the ‘60s and early ‘70s?

This is a depressing but important period of trans history that has not really been written about, except in my work. The broader message is that even in a period of visibility (I have in mind our current situation, the so-called transgender tipping point) there can be a reaction, a backlash. Nothing can be taken for granted. Another lesson relates to the attitudes and practices of those supposedly treating transsexuality during that period. It was not an especially auspicious period in US medical and psychiatric history – and sadly some of those attitudes are still with us today. It is important that this darker side of trans history is known.

How do developments in surgery intersect with the broader history?

This is a perceptive question, which I am not sure that I can answer in a few words. Surgery is only one of the treatments for transness, but it recurs in trans history: from the sporadic attempts at bodily modification in the earlier twentieth century, through the privileging of rather crude forms of surgery during the transsexual moment, to the more sophisticated, but optional, surgical solutions of transgender times (including complex facial surgery).

Surgery was central to transsexuality but, ironically, few trans people were in the position of affording it, even when they wanted this form of treatment. Under transgender (from the 1990s on), surgery was no longer deemed so pivotal to trans transformation and this has been enshrined in guides to health-care professionals. Still, surgery in its varied forms (including self-surgery and surgery by unregistered practitioners) is important in trans history. I think that Eric Plemons put it well when he said that while surgery did not define trans people it was important in many of their lives.

What do you mean by the ”medical model” and how has the book resisted this approach?

The medical model refers to transsexuality and transgender as defined and determined by the medical and psychological practitioners, those who decided who was suitable for treatment, how they were treated, and indeed the very definitions of their supposed ailment. Not only does the medical model determine the real-life situation of trans people – at least those who seek medical help – but it can affect their history (in the sense of how their experience is chronicled).

If historians and other commentators and researchers are reliant on the sources generated by doctors and psychologists and psychiatrists – a vast medical and psychological literature – then they can be in danger of being captured by their sources, by the medical model. The way around this is to either ignore the medical literature, which would be counter-productive, or to read critically against the grain of the dominant paradigm. Crucially, there is also a developing literature generated by trans people themselves – often, though not inevitably, critical of the medical model.

Certainly, "Trans America" deals with people who lived their lives almost oblivious to the medical model, or who consciously carved out ways of being and seeing that did not adhere to the dominant categories of gender and sexuality or of transsexuality and transgender. Trans was formed in the streets as much as it was in the consulting room and surgery.

Why is the erasure of trans history occurring?

I wish that I knew the answer to this question. When reading trans memoirs and commentaries I was struck (I give examples in my book) by either the absence of any sense of history, or the feeling that the memoirist or commentator was oblivious to others who had preceded them. The answer about the erasure of history may lie more generally in culture and society, but it seemed tragic that there seemed to be so many young trans men and women, exploring and discovering their transness, longing for exemplars or for other examples that might explain their feelings, yet oblivious to instances either in their own culture or in the past. Undoubtedly, the internet now provides examples from their own culture, yet I am not sure that it indicates the possibilities of the past sufficiently.

How is your book seeking to counter this trend?

Hopefully in the depth and variety of trans history conveyed in its pages. I think that my book could provide what CN Lester has called ‘the comfort of companionship’ for those who think that they are alone. People will have to read it first, of course.