This article is a preview from the Summer 2020 edition of New Humanist

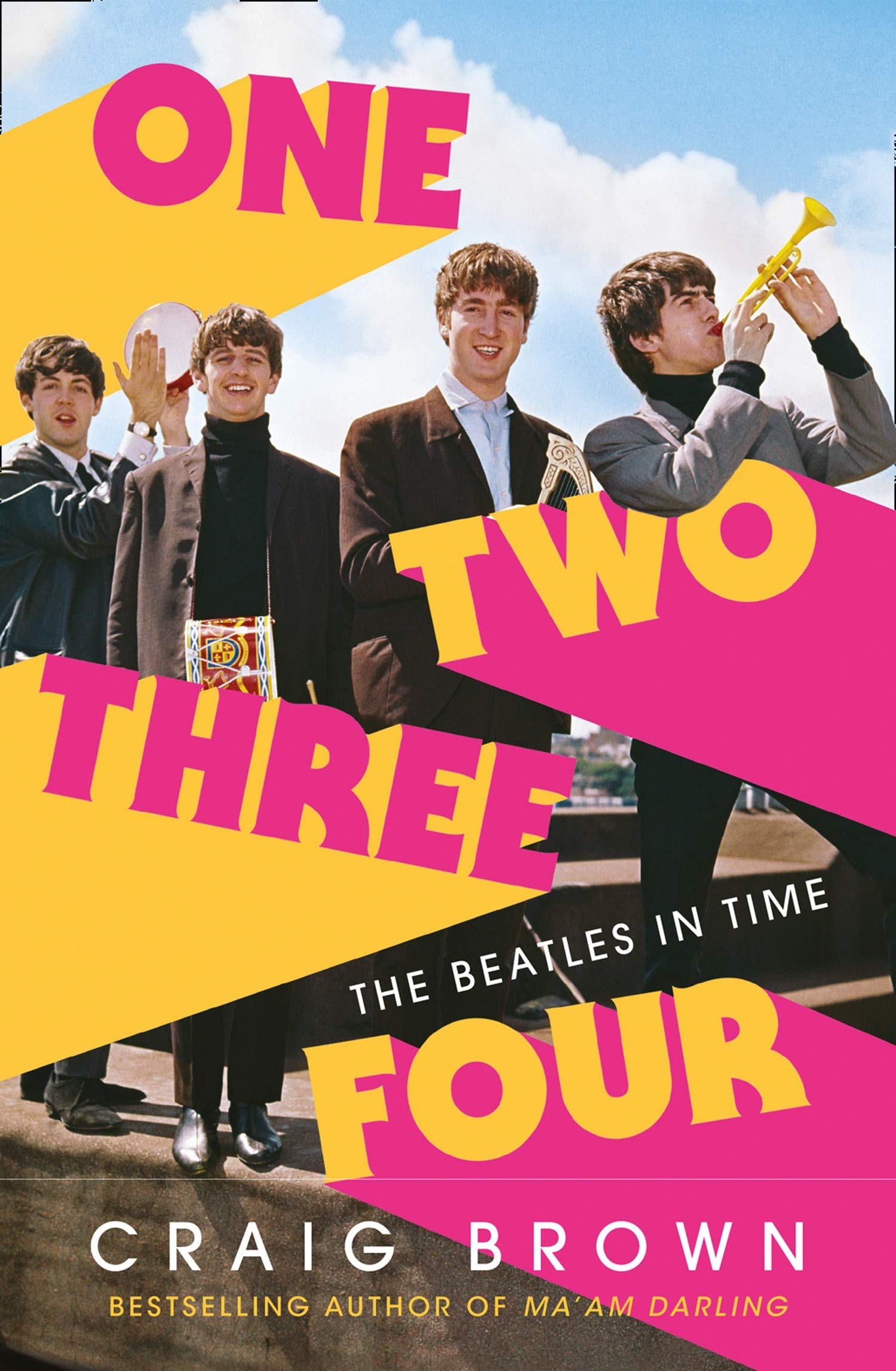

One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time (Fourth Estate) by Craig Brown

For any author, however good – and Craig Brown is one of the best – applying yourself to a book about the Beatles must endow a measure of the existential ennui which descends upon the photographer pointing their camera at the Taj Mahal. What’s the point? Everyone knows everything about it. As the exhaustive bibliography at the end of One Two Three Four amply demonstrates, the literary landscape has scarcely been parched, this last half century or so, by a drought of books about the Beatles.

Brown is a satirist by trade, probably best known for his merciless pastiches of other people’s diaries in Private Eye. In recent years, he has brought that talent for waspish observation to bear in acclaimed and original takes on the history book. One on One is a miscellany of the modern-ish world relayed through 101 encounters between key protagonists – Harry Houdini meets Theodore Roosevelt meets H. G. Wells meets Josef Stalin, and so on. Ma’am Darling is an episodic, tangent-rich and bleakly hilarious biography of Princess Margaret.

Both serve as templates for One Two Three Four. As One on One demonstrated, Brown is fascinated by the randomness of history, always alert to the fact that anything that has happened is merely one of an infinite number of things that could have happened, but did not. In footnotes and digressions he muses that had the Luftwaffe not bombed Liverpool one particular night in late 1940, Paul McCartney’s parents might never have gotten to know each other; had their son done better in his GCE Latin exam, he wouldn’t have been in the same class the following year as George Harrison; and so on. The odds against any rock group succeeding are colossal, not least because of the odds against that crucial combination of personalities even meeting.

The odds against the Beatles succeeding were more awesome still, on the grounds that they formed at a time when it was far from clear whether success, for a rock group, was even really an option. Brown illustrates their vertiginous ascent to the stars with a keen eye for the tiny detail which somehow reveals more than the most expansive canvas. As late as 1964, concerts in the UK closed with an obligatory post-gig broadcast, through venue speakers, of “God Save the Queen”. This proved a boon to the Beatles, who were able to flee premises ahead of the demented throngs which routinely pursued their Austin Princess, while “their fans remained inside, rooted to the spot out of respect for Her Majesty”. Such was the nation the Beatles transformed – followed thereafter by so many others.

One Two Three Four is not merely the story of the Beatles, but a sort of history of the world during the period in which the Beatles tilted it on its axis. Brown catalogues their impact on entire states – Indonesia and the Soviet Union were among those which legislated or propagandised against the menace posed by the Beatles’ hair – and on individuals. Brown has clearly read not only every book ever written about the Beatles but, to judge by the vast range of anecdotes included, every book ever written about the artists they influenced – which is to say every artist, pretty much.

As ever with Brown’s writing in any field, One Two Three Four is also very funny. Brown doesn’t much go in for zingers, punchlines or wordplay, instead relying on the deadpan description of the droll and surreal. There are especially rich reserves of both in the Beatles’ credulous interactions with Maharishi Yogi, and with Brown’s own conflicts with the passive-aggressive jobsworths conducting tours of Beatles heritage sites.

Of everything about the Beatles that retains the power to astonish, none seems more amazing now than the fact that their dozen studio albums were released in a squeak over seven years. (And, if you ever want to depress the heck out of yourself about the value of your life’s work, reflect that when the group split, the oldest of them, Ringo Starr, had only just turned 30.) This long book has something in common with the short career it chronicles: it could justifiably have gone on a while longer.