A beautifully executed crop circle depicting Channel 4's Richard and Judy appeared near Edinburgh shortly before harvest time this year. The papers naturally went to the soi-disant experts on cereology – in this case 'experts' seems to mean anyone gullible enough to spend large parts of their life seeking a paranormal explanation for these phenomena – who were obliged to concede that, no, it was indeed unlikely that visitors from another galaxy had flown half-way across the universe in order to imprint the faces of two daytime TV performers on a field of Scottish wheat, and then whizzed off home again, or possibly no further than the moon, where they might have managed to press the features of Dale Winton into the dust before moving on to the celebrities of a neighbouring solar system. In the end the Richard and Judy circle turned out to be a publicity stunt. Well, there's a surprise!

However, the 'experts' added – at least they did in the quotes I saw – the fact that some, or even most crop circles are clearly pranks doesn't mean that all of them are. A pleading note usually creeps in at this stage: please, they seem to be saying, leave us some of the crop circles for ourselves. Don't be greedy. Don't insist that they're all made by hoaxers. It isn't fair.

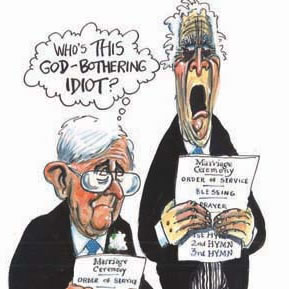

Phooey. Truth isn't something to be shared out equally, like eggs in wartime. It's true or it isn't. William of Ockham, the great English philosopher, spent much of his life in long fruitless religious debate, but then most thinkers in the 14th century did. (To be fair, he did point out that the existence of God was not susceptible of proof and rested entirely upon faith, which brought him as near to being an atheist as was prudent at the time.)

But either way Occam's famous razor should be supplied with every version of the Swiss Army Knife, or at least those sold to us newspaper reporters. The razor decrees that "entities [by which he meant the assumptions used to explain things] should not be multiplied beyond what is needed." In other words, if there is an explanation – in the case of crop circles hoaxers – then we don't need to invent spacemen from another planet, nor a race of very short people who live in the earth's crust and only emerge at night, which is another suggestion put forward in the past, even by people not under the influence of powerful hallucinogens. Or, to misquote Sherlock Holmes, once you have eliminated the frankly barking, whatever remains is most likely to be true.

Of course it is conceivable that space travellers concocted the first crop circles. Mere humans saw what a good idea they were, and how they attracted TV crews who came to admire the work, and started copying them, rather in the way that we learned how to make viaducts from the Romans. There isn't the tiniest shred of evidence of visiting aliens, of course, whereas there is a stack of evidence that hoaxers have been at work for years, most notably their detailed admissions. This means nothing to true followers of the paranormal, and it can be quite hard to argue against them. No mother working her way through her child's hair could find so many nits to pick. In the same way that American fundamentalists believe that Darwin's occasional mistakes invalidate the whole theory of evolution, they will seize on any detail, no matter how small, to prove their case by default.

If someone told you that rain was angels crying – and believe me, there are people out there who believe stuff that's every bit as wacko – you might reply that it's no such thing; it's condensed water vapour, which is why it only rains when there are clouds above us.

The paranormalist points out, triumphantly, that it sometimes rains out of a clear blue sky. You try to explain that sometimes freak air currents can carry rain in the upper atmosphere for miles before dumping it somewhere sunny, but by then it's you who are sounding flustered, you who are inventing bizarre explanations and unnecessary entities to avoid the perfectly obvious fact that rain is the tears of angels. Or quite often is.

A lot of people believed in the late Doris Stokes, a spiritualist who could fill great halls around the country with her act, which involved getting in touch with the dead. If you watched Mrs Stokes in action you could see all the weary old tricks: persuading people to tell her about their lives, then repeating it back as if it were her own discovery, 'fishing expeditions' in which she tries various alternatives until she hits the right one, and, as a Daily Mail investigation revealed, outright fraud. She papered the audience with people who had told her their stories, then repeated it back to them with assurances that the dear departed were very happy and sent their love.

"Ah ha!" her fans would say, "but she knew my uncle's name was Reginald, and he was suffering from gallstones. How do you account for that? Eh?"

The answer is, I can't. Maybe she made a few inquiries. Maybe it was a lucky guess. Are you sure she said "Reginald" and "gallstones" to you, or did they crop up in general talk and you thought they were about your uncle? And even if she did get something right, does that mean that the souls of the dead are jostling to talk through a middle aged woman sitting in the Fairfield Hall, Croydon?

Perhaps we should give up and let people enjoy their small delusions. Does it matter? Well, I think it does. There's quite enough misinformation in the world already. If a friend believes one of those Nigerian internet scams, you'd set him right. Why not about this kind of rubbish? Sometimes you have to be cruel to be kind. Or, in some cases, cruel to be cruel.