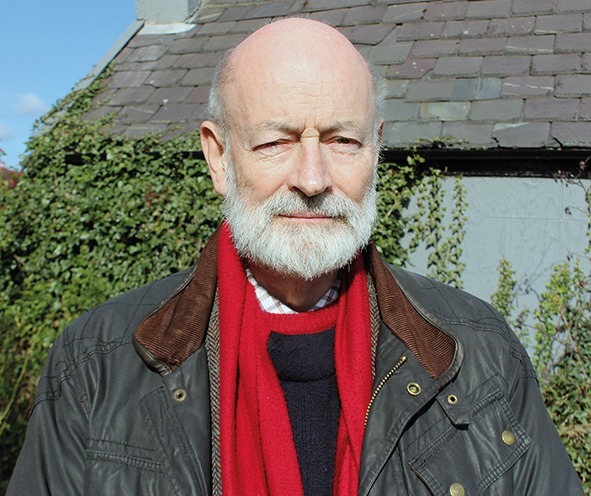

From the autumn 2020 edition of New Humanist.

Professor Raymond Tallis is a philosopher, poet, novelist and cultural critic. Until recently, he was also a physician and clinical scientist. Tallis is a patron of Humanists UK. His latest book is “Seeing Ourselves: Reclaiming Humanity from God and Science”.

You define humanism as “a sociopolitical movement, a cry of freedom, a call to arms, and a right to think for one’s self”. Why, then, do you think it needs more work as a philosophical concept?

Many humanists think their main job is to be critical of religion and to embrace the only alternative, which is naturalism. They assume an obligation to understand themselves in naturalistic terms: that essentially human beings are organisms, they are part of nature, and they were generated by Darwinian processes. This view says: if you really want to understand human beings you need to dig deep into the biology of humanity. A great deal of this has been influenced by a move towards neuroscience to understand human nature. But there is serious unfinished business in humanism. It shouldn’t fall victim to naturalism – and it should give a positive statement about what we are.

You are especially critical about what you call “neuromania”: the idea that we are our brains.

You can see this very clearly when you look at neuroscience’s major failure to explain human consciousness in terms of neural activity. It’s perfectly obvious that in order to be conscious as a human being you need to have a functioning body, nervous system and brain. But that is not the whole story. What is missing in that story is what humanists need to look at very carefully.

Can humanists take anything positive from faith?

You would be a very strange humanist if you simply dismissed [religion]. After all, it’s something that has been so important in the history of humanity. We need to address those issues that religion seemed to falsely address: namely, the tragedy of life – the fact that everything we do is eventually cancelled out and in the end we lose everything we have.

We don’t seem to have within our lives a convergence point where all our hopes, ambitions and fears meet into one [cohesive] narrative. Religion provides that, and also consolation, by telling us that we are ultimately immortal. While we are alive, religion [claims] there is a single point and purpose to all our projects: to worship God. I reject that last part completely. But what I don’t reject is the need that religion addresses. That is where more work needs to be done by humanists.

What about mortality? Maybe existentialism is the nearest philosophical idea that challenges religion in this regard?

Well, as Albert Camus said, one must imagine Sisyphus happy. [The king in Ancient Greek mythology whose punishment in Hades was to roll a boulder up a hill, only for it to roll down again.] I wonder if he really was, though. But yes, one can embrace tragedy and contentment in life. But it’s not a very cosy embrace. In the end we cannot escape the fact of our mortality, which is the fundamental fact of our life. We can, of course, distract ourselves by helping others and thinking of a better future.

You’re highly critical of the New Atheism movement. Where do you believe they went wrong?

Take someone like Sam Harris. He is very much a naturalist who ends up with all sorts of conclusions that counter our humanist outlook. He doesn’t believe in free will, for example, because he cannot derive it from a materialist account of humanity. But free will is a foundational stone of human dignity and for our place in the world. Other thinkers, such as Richard Dawkins, overlook the nature of consciousness and our shared consciousness, where we transcend our condition. This cannot be understood simply in Darwinian terms. Making sense of our transcendental nature should be a central preoccupation for the humanism of the future.

You quote Dr Samuel Johnson who famously said that “all theory is against the freedom of the will, all experience is for it.”

Well, free will doesn’t work in theory but works in practice. One argument against free will says: actions are material events. Every material event is caused by prior events. And if you eventually trace those physical events backwards you can see that those events that constitute [one’s] biography appear to have a cause or ancestry before [one] was born. The other argument against free will is that everything that happens in nature is regulated by laws, which are – by their very definition – unbreakable.

How is it possible to have free will, then?

My argument is that we don’t exercise our free will by breaking the laws of nature or by becoming some kind of entity that can cause things without itself being caused. We are outside of nature. We occupy a virtual space of possibility, one of which is a space that is an extension of time.

Those who don’t believe in free will would find it very difficult to figure out how we discovered the laws of nature. How did we get to be manipulating things in laboratories in order to discover these laws? The processes by which we discover the laws of nature are not by themselves driven solely by the laws of nature. And we use these processes to then manipulate the world to deliver our envisioned ends.

Can you speak about the complicated relationship we have with time and how it relates to our conscious experience?

Material objects tend to be fixed in the particular time that they are, or in which they occur. But a conscious experience is not fixed. It is informed by the past and reaching towards the future. So, we are never fixed at the physical or “clock time” in which we are bodily located. This was something that was acknowledged by Albert Einstein. He saw that there was no place for the future, the past and the present in physical time. Tensed time had no place in the general theory of relativity. But tensed time is absolutely central to our everyday life. That is another way of capturing our distance from the natural or material world.

The world appears to be becoming more religious: why is this?

That is mainly a demographic consequence: where there is a rise in religious belief, there is a much bigger increase in the population. So there is a secularisation in western Europe, but not worldwide. But even in countries where there is an embracing of religion, there is still a secularisation of ideas, in terms of people looking for solutions to their problems. Technology is embraced worldwide, even in countries where religion dominates. And people will look towards their mobile phones in a practical sense, rather than to prayer, for solutions to their problems.

Do we not need myths to live by?

The last thing we need is religious myths, because we know the problems they have caused in the past. Also, you cannot say: “It’s impossible to live without myths, let’s invent a myth to live by.”

Can you explain your resistance to the idea of the self as a fiction?

Many philosophers [like Daniel Dennett] think the self is unreal because you cannot see it in the brain. They say this is not a failure of neuroscience, it’s simply evidence that the self is an illusion. But those that argue that the self is an illusion have to explain how we have arrived at that illusion. It requires an awful lot of self to argue for the illusion of the self.