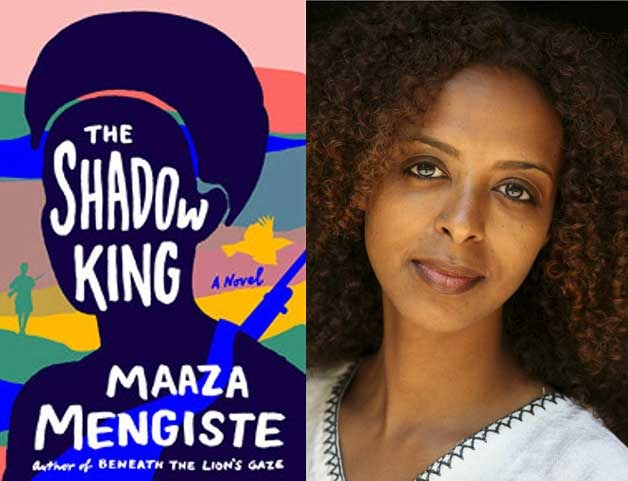

The Shadow King (Norton) by Maaza Mengiste

The Wife’s Tale (Fourth Estate) by Aida Edemariam

Queen of Flowers and Pearls (Indiana University Press) by Gabriella Ghermandi

In the final act of Maaza Mengiste’s latest novel The Shadow King, a group of guerrilla fighters, armed with knives and old rifles, ambush a group of Italian soldiers in the foothills of Ethiopia’s Simien mountains. Chief among them is Hirut, a young, orphaned girl, who has volunteered to help liberate her homeland from the invaders. As Hirut charges at her foe, Mengiste evokes a Homeric chorus, which lets out a battle-cry, dedicated to the “multitudes who rushed like wind to free a country from poisonous beasts”. This is one of the most powerful moments in a narrative that subverts all expectations about how war is depicted in fiction.

The Shadow King is based on a true, often overlooked story. In 1935, Mussolini’s army set out to conquer Ethiopia, in the hope of extending Italy’s colonial domain. Despite his army’s modern weapons, however, small partisan groups, like those depicted in the book, held the invaders at bay for months. In fact, their resistance was so strong that to secure victory the fascist generals resorted to using chemical weapons – mustard gas – which they dropped indiscriminately from planes, on militia groups as well as the civilian population. Italy’s rule over Ethiopia would last just six years, but it had long-term consequences: 50,000 were killed during the occupation, and some of the country’s farmland remains contaminated to this day.

The Shadow King is a modern-day Iliad, a celebration of Africa’s forgotten heroes and their epic struggle against European colonisers. It’s also an important historical text. While few – if any – western nations have faced up adequately to their imperial past, the level of collective amnesia in Italy is particularly severe. In the 1940s and 50s, the newly founded republic introduced colonial history to schools in an effort to emphasise the government’s split from fascist-era foreign policy. Nevertheless, it was the botched nature of the expedition in Ethiopia, and the ultimate failure of the mission, that passed into public consciousness. As a result, many today still operate under the assumption that Italy’s African campaigns were less horrific than those of, say, Britain or France.

In reality, the fascist (and pre-fascist) occupations of Libya, Eritrea and Somalia, as well as Ethiopia, were barbaric. Hundreds of civilians were killed in two massacres in 1937, at Addis Ababa and the Debre Libanos monastery. These are just two atrocities that have been whitewashed out of public consciousness. There are many others. Even in Ethiopia, where Italy’s crimes are more intimately felt, people have tried hard to forget these events. At the start of The Shadow King, Hirut herself struggles to speak up: “she does not want to remember”, writes Mengiste, “but she is here and memory is gathering bones.”

The publication of The Shadow King comes at a strange moment for Italy. Public awareness about the country’s colonial past has faded over the past few decades and nostalgia for fascism is on the rise. The media often points to the growth of thuggish street movements like Casapound and Forza Nuova to illustrate this point. In reality, though, fascism permeates far deeper into the collective identity. Matteo Salvini, the leader of Italy’s most popular party, the League, regularly quotes Mussolini, speaking of the need for a “mass cleansing”, and has called on his supporters to embark on a new “march on Rome”. In bars and cafés, it’s not uncommon to hear people speaking fondly about “Il Duce” (an affectionate nickname for the Italian dictator) or to quip, with various degrees of seriousness, that things were better “quando c’era lui” (when he was around). Sometimes, these sentiments are expressed explicitly in terms of imperial nostalgia. In 2012, Ercole Viri, the mayor of Affile, a small town outside Rome, used public money to build a monument to Rodolfo Graziani, a fascist general who sanctioned the use of chemical weapons in Ethiopia in the 1930s. Viri maintains that “in his colonial career and at home, Graziani was a proven hero.”

In recent years there have been several attempts to counteract such distorted views. Mengiste’s fictional colonel in The Shadow King, Carlo Fucelli, is a case in point. At the beginning of the novel, he appears to be a confident, cold ideologue. As the narrative progresses, though, we see that his loyalty to fascism is really based on his own insecurities and sense of impotence. Even his most evil gestures – as when he commands his soldiers to drop Ethiopian prisoners one by one off a cliff to their deaths – are based more on a need to impress the men around him than on some innate hatred of the local population. Other authors have provided similar deconstructions of this highfalutin masculinity.

In her novel Queen of Flowers and Pearls (2015), for example, Gabriella Ghermandi, an Italian-Ethiopian writer from Bologna, collates stories from the oral tradition to expose the everyday crimes committed by men like Graziani. Her narrator, Mahlet, a young girl, listens to stories from friends and relatives and acquaintances; learning in the process about the implications of this history on her own identity. This is a bildungsroman, in which the protagonist’s own life in modern-day Europe is transformed by revelations about Italian violence. Then there is The Big A (2016), by Giulia Caminito, which depicts Mussolini’s colonial territories as a place of cosmopolitan mixing, where working classes of all nationalities co-existed and shared frustrations about the brutal behaviour of the fascist elite.

One of the most striking things about this new flourishing of postcolonial texts is the particular contribution of female authors. In the past, most books critical of the Italian empire – like Ennio Flaiano’s A Time to Kill (1947), which won the first ever Premio Strega literary prize – have focused on male guilt and how white Europeans have struggled to live with their culpability. Today, that conversation is becoming more nuanced; less Italo-centric and less skewed towards a purely masculine experience. This gendered dimension is far from incidental. It is transforming our shared understanding of colonial history itself. Flaiano’s novel, for example, presents women as being particularly opposed to war on the basis that conflict kills the men they are close to, or reliant upon. In The Shadow King, by contrast, Mengiste demonstrates how women also fought willingly, against both the invaders and domestic manifestations of patriarchy. Early on in the narrative, Hirut is raped by an Ethiopian general and spends much of the novel afraid of further sexual assaults. It is only when she is drawn into direct conflict with the Italians that she feels “where she should be, at the centre of the world, spinning free, finally”.

Queen of Flowers and Pearls is similarly unflinching in the face of unspoken and uncomfortable truths. At the start of the novel, Mahlet appears naïve and ignorant of her home country’s past. As the plot progresses, however, it is she, a teenage girl, who breaks down the psychological and political barriers constructed by a previous generation to uncover the ways that Italian colonisation engendered an inferiority complex among the Ethiopian population.

Perhaps the most powerful of the recent releases, though, is The Wife’s Tale (2018) by the Ethiopian-Canadian journalist Aida Edemariam. This non-fiction biography – structured according to the Coptic calendar – tells the life story of the author’s paternal grandmother, Yetemegnu, who lived in the area around Gondar in Northern Ethiopia for much of the 20th century. Here the major historical events – the famines and massacres, protests and revolution – are secondary to the personal accounts of everyday rituals of childcare and cleaning. During the Italian invasion, for example, Yetemegnu is mainly concerned with the fate of sycamore trees, vegetable plots and animals. She wonders if the Italians will support the local church and if the rumours are true that they are less racist than the British. She observes that “pasta looked like hookworm” and perplexedly grinds up sweet galeta biscuits to make a spicy paste. History can often be abstract and alienating. In this biography the reader is presented with an everyday story of individual resilience, in which Ethiopia’s landscape, culture and traditions are treated not as exotic counterpoints to European experience, but as worthy subjects for narrative in their own right.

Fifty years ago, many writers simply wanted to remind the postwar public that Italy ever attempted to build an empire. This remains an important mission. Yet these recent texts demonstrate a maturing of Ethiopia’s postcolonial tradition and an increasing sensitivity to how and through what prisms we remember European imperialism.

In Italy, writers of African origin are often instrumentalised to become purely political actors, whose main job is to counteract the false histories propagated by the far right. Yet reducing these novels to this task alone is to misunderstand both the history of colonialism and the function of literature in society. It is not these writers’ responsibility to fill in the gap where education and political institutions have failed, but to develop nuanced characters that call into question stereotypes of all kinds.

What really distinguishes these books is their commitment to communicating how complex and contradictory human nature remains, even – perhaps especially – amidst atrocities where the line between good and evil seems clear. We’ve become used to art which explores the psychological nuances of fascists and other colonial administrators. Thanks to this new wave of books, a similar sensitivity is finally being afforded to those who resisted them.

From the autumn 2020 edition of New Humanist.