Cloud islands, they are called. The peaks of the Usambara Mountains in Tanzania rise so high that fogs form on their slopes where the cool mountain air meets warmer currents rising off the sea. The climate has created a unique ecosystem, as real islands do, and much of the wildlife is unique to the area. Even there, much of it is vanishingly rare. The Amani tree frog, for instance, was discovered in 1926 inside a wild banana; it has never been seen again.

At least, that is how things were, Cal Flyn writes in Islands of Abandonment, her consistently rewarding, eloquently provocative new book. In 1902, the authorities in what was then German East Africa built the Amani Biological-Agricultural Institute there, planting several thousand species of tree and plant. But no one tended the gardens. Researchers worried that indigenous species would be overrun. The concerns were well founded: the umbrella tree ran riot, at one point accounting for a third of new-growth forests.

More than half of the most invasive plant species in the world have escaped from botanical gardens. One lake in Java has lost 70 per cent of its surface to water hyacinth, derived from a garden 500 miles away. The escape of a species of giant rhododendron from Kew in the 19th century was so notorious one newspaper ran a cartoon of the plant scaling the walls and absconding on a number 27 bus.

But at Amani, an interesting thing happened. Sometime this century, a native fungus started attacking the umbrella tree, wreaking havoc on its numbers. Given enough time, nature will find an equilibrium. As for humanity, even when we try to do good, we often do harm. “We run the Earth as if it were one giant botanical garden to tend: passing judgement on species, playing God,” Flyn writes.

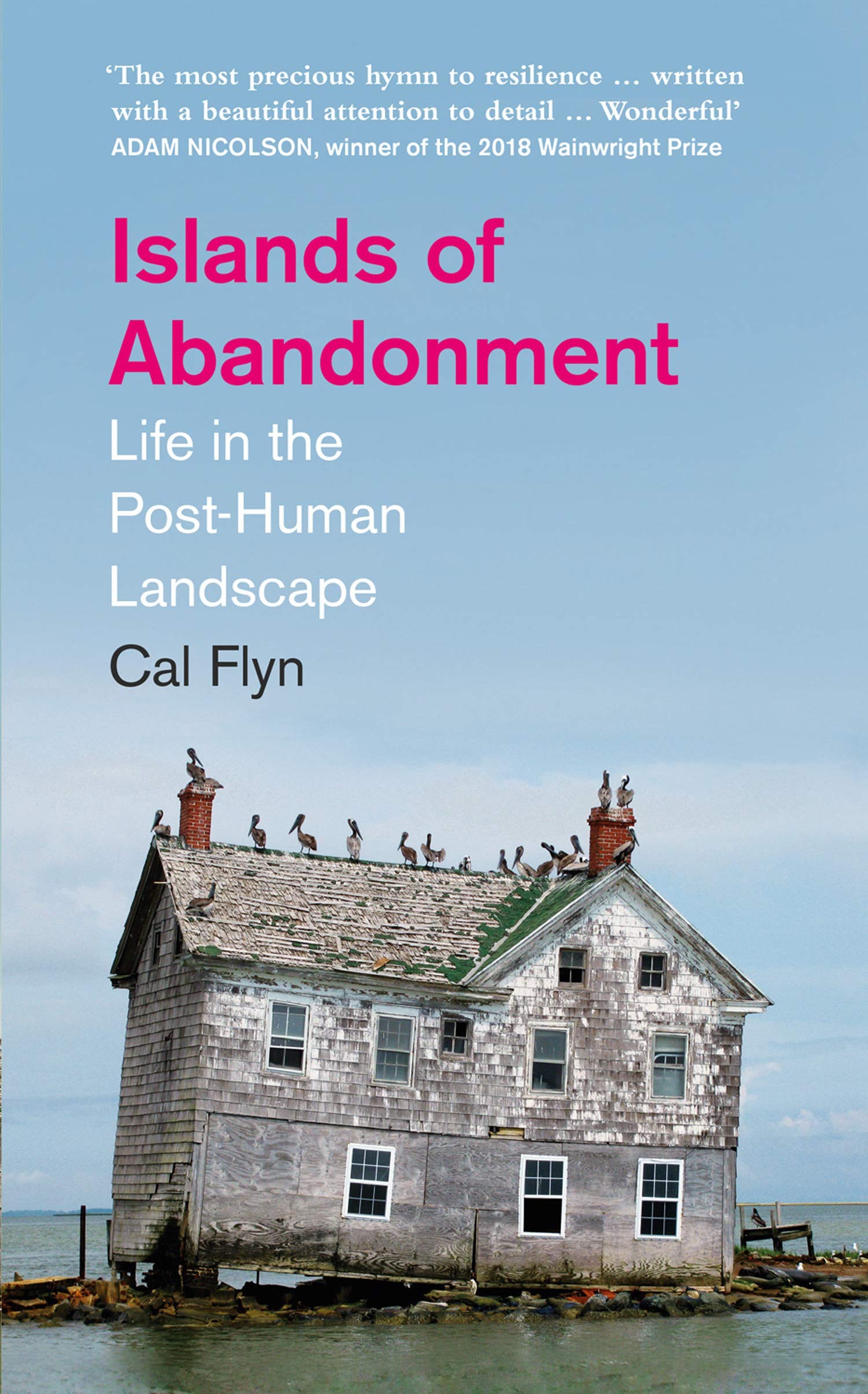

Islands of Abandonment is about what happens when we stop. Stop with the damage, sure: the ravages of war, industrialisation, ideology. But stop interfering too. Step back, let things happen. Nature is an orchestra that wants to improvise; we should stop insisting it sticks to the score. In pursuit of this thesis, Flyn reports from some extraordinary locations: the book’s itinerary includes a First World War chemical weapons site where the soil is 17 per cent arsenic; a derelict fertiliser plant that left behind levels of dioxin which reach 1.65 billion times the safe limit; and Chernobyl’s Dead Zone, the most radioactive place on the planet. It is a brave book, in more ways than one.

But, without once flinching from the horror, Flyn finds cause for hope in even the most toxic and despoiled of environments. Left alone, wildness revives. Around the world, there are now some 2.9 billion hectares of what is called “recovering secondary vegetation” – former arable and pasture, and regrowing forests – more than twice the area under crop. Russia may have met the terms of the Kyoto Protocol through the abandonment of farmland alone. Flyn describes a fish which can survive in waters so saline the human equivalent might be drinking petrol. She says it has a superpower: adaptation. But really, it is nature – the vast and intricate ecosystems of the planet, almost transcendental in their interconnectedness – that is the source of this power, as Flyn sets out.

Why, though, are we unable to let go? One of the great strengths of this subtle and profound book is that it is also a quiet exploration of aesthetics in the natural world, of how we conceive beauty and value; not many books of nature writing cite Marcel Duchamp approvingly. More, Flyn understands that our relationship with the planet is conditioned by deep-rooted cultural frameworks and eschatologies. With an apocalypse coming, we look back guiltily at our Edens; the psychologies of transgression and redemption, sin and forgiveness, stalk our every thought.

But perhaps the boldest choice Flyn has made is to include urban sites blighted by population loss and industrial decline – and the people who live in them – among her islands. One chapter is dedicated to Detroit, a city whose population has shrunk by some two-thirds and in which 80,000 properties are now vacant, crumbling into ruin. Why do people stay? Why have people returned to the Dead Zone around Chernobyl? Why does any living thing return to these toxic, tragic places?

“It is nothing like it used to be,” a Detroit resident tells Flyn. “But it is home.”