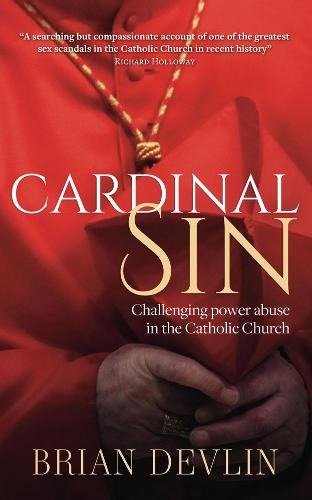

Cardinal Sin: Challenging Power Abuse in the Catholic Church (Columba Press) by Brian Devlin.

In 2013, just before departing for Rome to take part in the election of a new Pope, the senior most official of the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland suddenly resigned. Cardinal Keith O’Brien had been accused of past sexual misconduct by four serving and former priests, who in their frustration had taken their story to the media. As the news went public, O’Brien announced his retirement. Within days he issued a statement announcing that he would not contest the allegations. Soon after, he vanished from public life.

These events were unprecedented and spectacular. Cardinal O’Brien was an instantly recognisable figure in Scotland. Habitually dressed in grandiose clerical vestments, he was a staple of public life and hobnobbed with political leaders and public figures, including the disgraced former First Minister, Alex Salmond, as well as, pertinently, the notorious sex offender, Jimmy Saville. O’Brien’s had long been a loud voice advocating privilege for religion, and Catholicism in particular. He demanded exemptions for the faith from progressive legislation, including the introduction of same-sex marriage. Ironically, O’Brien’s political campaigning took place at a time when Scotland had become an overwhelmingly secular society. Social liberalism was increasingly associated with a rejuvenated national identity.

O’Brien seemed particularly fascinated and preoccupied by male homosexuality, which he considered to be a “moral degradation”, and LGBT people “captives of sexual aberrations”. His outbursts rarely referred directly to gay women, trans people or non-binary people, but imagined homosexuality as associated with a deviant form of masculinity. Yet they told of O’Brien’s own troubled sexual identity and the culture in which it was formed. He was a deeply closeted gay man who had abused his clerical status to groom younger men, often trainee priests. As Brian Devlin writes in Cardinal Sin: Challenging power abuse in the Catholic Church, his account of being the “whistleblower” whose endeavours precipitated the cardinal’s fall, “With apparently little regard for the consequences, O’Brien pounded in his pulpit, outraged by the sin and sexual savagery he saw all around him, while at the same time he abused his power within his own circle: those who he had a special duty of care for.”

Cardinal Sin is a memoir which is by turns fascinating, curious and admirably reflective. It stands not as a simple account of the downfall of a sexual predator, but rather a thoughtful religious autobiography. We learn of Devlin’s journey into the priesthood as a vulnerable young man, his resignation from it, and his attempts over subsequent decades to reach composure with his troubled past and his shattered clerical identity. He offers an inside account of his ultimate struggle to hold O’Brien to account for his actions in the face of obstruction from the Catholic authorities in Scotland and Rome, as well as an assessment of the substantial fall-out from the affair.

Gendered and sexual regimes

Devlin’s own journey to priesthood began at St Andrew’s Seminary in Drygrange, an elite institution buried deep within the Scottish countryside. Devlin was to quickly discover that Drygrange was “not a holy place” but instead a deeply dysfunctional and “breath-takingly strange” environment inhabited by bewildered students and troubled teaching staff. Here he encountered Keith O’Brien, trendy priest, “Irish charmer” and spiritual director of the college, with special responsibility for first year students. O’Brien groomed Devlin, groped him on car journeys and during prayer sessions, and, finally, assaulted him in his bedroom one night after a boozy dinner. The following morning, he manipulated him into silence. Devlin experienced an epiphanic moment: Keith O’Brien was a “cynical conman and sham”.

Devlin is a genial and insightful narrator. His memoir has plenty to say about the Catholic Church’s tortured relationship with same-sex desire between men. He also provides an insightful depiction of the gendered and sexual regime that moulded O’Brien. Sex between men was criminalised in Scotland until 1980. Historians Roger Davidson and Gayle Davis have observed that even the name of the country’s first gay rights organisation, the Scottish Minorities Group, was closeted. Homosexuality was a subject surrounded by silence and dread - a sociological survey of Glasgow teenagers in the early 1960s recorded that it was a subject that inspired “real fear” on the part of boys. Many people simply did not know much about it.

Devlin was among these. Yet at Drygrange he found a barely concealed queer subculture, where he was “astounded” by sights including same-sex couples perambulating the grounds arm in arm, and “big hairy men” who “giggled as they chased each other around the pool table”. All the while – despite it being forbidden - a certain version of male homosexuality was promoted, with students being admonished by O’Brien to conduct themselves as “manly men”.

It is instructive, given O’Brien’s life in the closet, that he told trainee priests to conform outwardly to normative masculinity and to maintain discretion and secrecy. He further used religious mechanisms and culture to absolve himself from “sins” and to ensure the silence of his victims. But was O’Brien, in some sense, a victim as well? He was socialised at a young age into spiritual sadism and unremitting homophobia. As far as is known, he was unable to own his own sexuality until his dying day. He died in exile and disgrace. Yet no excuses can be made. He continually abused his position of power and trust, and he was a monstrous hypocrite. Ultimately, O’Brien could have chosen to behave differently. He could also have been courageous enough to leave the priesthood and live a more honest and authentic life.

Throughout his book, Devlin ponders his own religious subjectivity. He wonders whether, despite his crisis of faith due to the depredations of O’Brien and the narcissism and grandiosity of members of the Catholic Church’s ruling hierarchy, he remains a priest in a “deeper and more personal way” than that associated with the celebrating of ceremonies. Devlin’s residual attachment to Catholicism - he describes himself as a “Collapsed Catholic” and makes clear that Catholicism remains central to his identity - suggest that perhaps they cannot. He insists that his book tries not to write from a place of anger and hurt, and he finds himself unable to hate an organisation which has caused him significant distress and emotional trauma.

The final section of his book is concerned with hopeful proposals for the delivery of liberalising changes, such as the ordaining of women priests, which Devlin hopes might salvage a troubled Church. Many readers will surely wonder if such measures will ever be implemented. Even if they can, would it all be worth it? Does the Catholic Church deserve Brian Devlin?