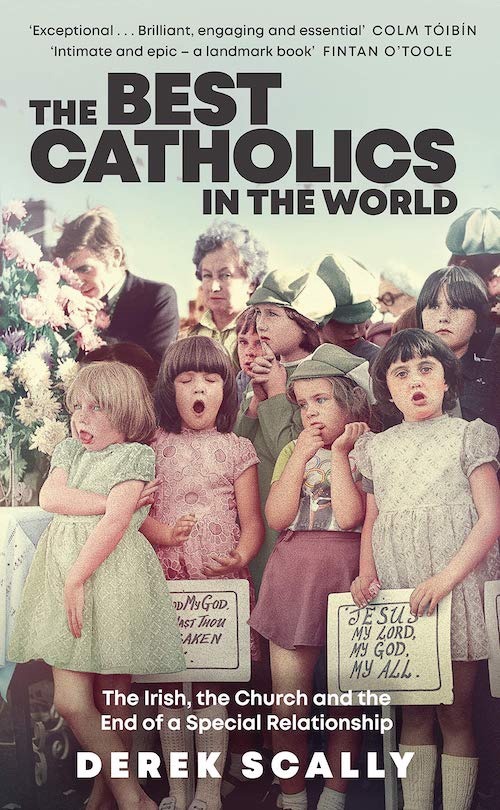

The Best Catholics in the World: The Irish, The Church and the End of a Special Relationship (Penguin) by Derek Scally

When Pope John Paul II visited Ireland in 1979, he drew an audience of over a million – around a third of the country’s population – to mass in Dublin. Barely three decades later, the moral and political authority of the Catholic Church in Ireland had collapsed, destroyed most of all by devastating revelations of clerical sex abuse and cover-up. How and why Ireland lost faith in the Catholic Church, and how it feels about Catholicism now, is the subject of this book. Derek Scally is a Berlin-based Irish journalist who returned to his homeland to explore how his and his country’s Catholic past “went from rigid reality to vanishing act” and to “reflect on the trauma that remains”.

Post-independence Ireland was not quite a de jure theocracy, but for many decades it was certainly a de facto one. The 1937 Constitution of Ireland explicitly recognised the “special position” of the Roman Catholic Church “as the guardian of the Faith professed by the great majority of its citizens”. This provision was removed in 1972, but the might of the Catholic Church in Ireland lay less in formal constitutional power and more in the societal influence it wielded, particularly over education and health.

This influence was seen in episodes like the “mother and child” scheme controversy in 1948, when the socialist health minister Noël Browne had to resign after his healthcare programme was deemed contrary to Catholic teaching. From 1937 to 1995 divorce and remarriage were not permitted in Ireland. For many decades contraception and abortion were also prohibited (even now, following the 2018 referendum, access to abortion remains fairly restricted). Censorship was also extensive.

The reasons why the Catholic Church came to have the whip hand over Irish society are complex. In the 19th century parts of the Irish independence movement had non-sectarian – or even, to use later parlance, secularist – leanings. The 1790s Irish independence leader Wolfe Tone famously sought to “unite Catholics and dissenters” and the authors of the 1867 Proclamation of the Irish Republic declared in favour of “absolute liberty of conscience, and the complete separation of church and state”. But after partition and independence in 1922 the Catholic Church manoeuvred itself into a societally dominant role. The version of Catholicism which prevailed thereafter was a particularly harsh, abusive and anti-intellectual one: “a mental prison to be endured,” as Scally describes it.

An issue which permeates much of his book is the extent of societal knowledge of, and complicity in, the abuses perpetrated by the institutional church. When it came to clerical sex abuse, so many people “knew but didn’t know”. As Scally says, “Survivors of neglect and abuse are the victims. Those with power carry the guilt. And what of those of us in between? Where do we place ourselves on the sliding scale between innocence and complicity? Can we separate guilt from shame, and begin exploring?”

This raises many interesting questions, including about the conformity and deference so prevalent in 20th-century Ireland, which Scally examines with skill and subtlety. I would like him to have said more about those who did resist and challenge Church power in Ireland, and what differentiated them from those who didn’t. But perhaps that would be a different book. This is not a formal history, but rather an attempt at understanding how a society feels about its recent past, and how it comes to terms with it. On that aspect, Scally draws some interesting contrasts between Ireland and another society he knows well and which also carries the burden of history: Germany.

Many Germans consider that while no one alive today carries blame for the Nazi era, citizens have a moral responsibility to understand and embrace their history.By contrast, in Ireland, Scally sees a reluctance to analyse the past and to grapple with what the Church’s overweening power did to Ireland. “We have museums for whiskey, the GAA [Gaelic Athletic Association], the Famine, Jewish history, tenement life, James Joyce, leprechauns – but not for the most influential institution in Irish history.” Meanwhile, the promised memorials to the victims of the Magdalene Laundries and other institutional abuses have yet to appear. Too many people would rather not talk about it. Scally ends this beautifully written and nuanced book with a powerful – and, I think, unanswerable – plea for Irish society to embrace much more openly and honestly the “complex events in our contested Catholic past”.

This piece is from the New Humanist winter edition 2021. Subscribe today.