There is something “anti-Descartian” about consolation: I feel, therefore I am. While we all think more or less the same (there are many people and few ideas), when I stub my toe, only I feel the pain. Even more significant, when my heart breaks, it’s only my world that crumbles. “The basis of the self is not thought,” wrote Czech novelist Milan Kundera, “but suffering,” which he considered the “most fundamental of feelings”.

Fundamental or not, suffering alone cannot dictate our state of being. Equally important is how we cope with grief and misery, how we console ourselves and grow and learn. Through that redemptive process, consolation has immeasurably shaped art, politics and religion. Giving form to that immeasurability was the task Canadian author and historian Michael Ignatieff set himself in his latest book, On Consolation. Looking at 17 historical figures, from the prophet Job to Abraham Lincoln to the 20th century doctor Cicely Saunders, he draws a beautifully clear map of how the search for consolation has evolved throughout the centuries and come to define the worth of human life.

In late 2021 I visited Ignatieff at his loaned flat in Vienna’s stately Josefstadt district. Snug in his study, Ignatieff easily assumed the role of the boffin, holding court over a cluttered desk dominated by a sepia globe, the walls behind him hung with esoteric artwork and an antique map of Venice. His own books occupied almost an entire shelf of that bookcase, their topics a wide variety of philosophic subjects: pain, honour, human rights, morality, and empire. But it could be said the search for solace has been his longest pursuit, forming a solid basis for some of his best work, from 1985’s The Needs of Strangers, through 1987’s The Russian Album, to 2017’s The Ordinary Virtues. His prior enquiries prepared him well, and make On Consolation a thorough examination of how the sentiment we know as consolation came about, and how it has changed over time.

Of the book’s germ, Ignatieff recalled a choral performance of the Psalms staged in Utrecht. “I began to wonder why a non-believer like me would be moved and comforted and possibly consoled by religious language,” he said. “That sent me to look at the Psalms in detail, and the Hebrew Bible, and Saint Paul, and on and on.”

That was before the Covid-19 pandemic, and his preoccupation with consolation seemed strange to friends and family, who assumed some tragedy had befallen him. It hadn’t, though he admitted to being drawn to moments of “real loss, real bewildering, disabling loss…the moments that flatten you.” He paused, as though realising it sounded somewhat desperate, adding, “I don’t think I’m a depressive character, and I don’t wish to imply so. Life is pretty damn good.”

There is a strong vein of positivity that runs through the book. Consolation might imply a dour topic, and there are moments of desperation in the book—imprisonment, death, sickness. But consolation is more accurately an act of hope and confidence, a definitive act of pulling oneself out of sadness. Ignatieff isn’t pedalling any feel-good remedies, and makes it clear early on that suffering isn’t something that can be avoided, let alone cured, even as society treats it as “an illness from which we need to recover”. One has a sense, speaking to Ignatieff, that he has become what Kundera called homo sentimentalis, someone who has raised feelings—even negative ones—to a category of value. “Comfort is transitory,” he writes. “Consolation is enduring.”

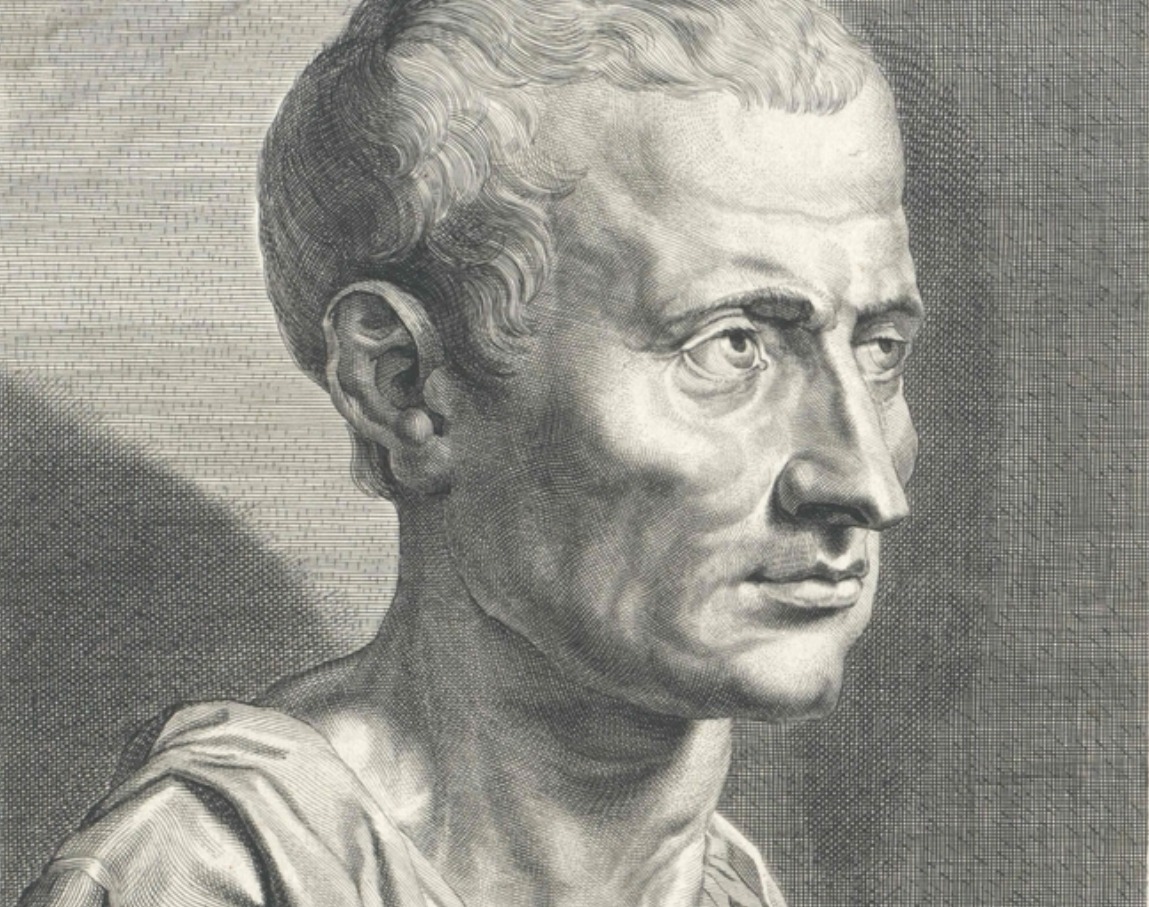

On Consolation threads together the revelations and wisdom of Marcus Aurelius, David Hume, Mahler, and others. “I began to see those connections, the most obvious one being Boethius, who faced death at the hands of the Barbarian king, inspiring Dante, who was similarly in exile in the same city, who then, in turn, inspired Primo Levi in Auschwitz.”

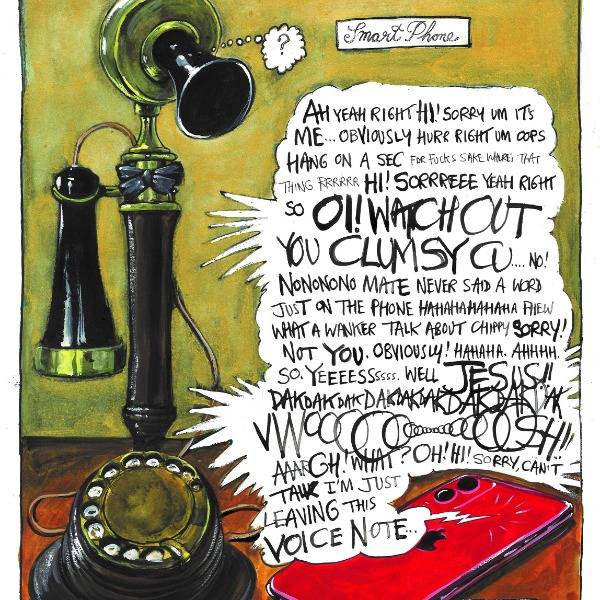

While Ignatieff holds up art as a timeless tenant of consolation, the book is also concerned with the limits of everyday language. “Words,” he writes, “just fall apart.”

“I think we’ve all experienced that when we try to console someone who is heartbroken,” Ignatieff said. “There’s no generic loss, there’s only loss for you and loss for me. And that means empathy is crucial to consolation. But anyone who tries to console finds this is where words break down, where silence descends over a room.

“Over and over again in these chapters, people are reflecting on the limits of words. Cicero writes these letters consoling other people – Consolatio [a philosophical work by Cicero] is [part of] a positive genre in the Roman stoic tradition – and then he loses his daughter. It’s one of the most distressing moments in life, and it’s where empathy comes to its limits, where words come to their limits, where meaning comes to its limits.”

The limits of what others can provide is one of the clearest messages of the book, and put me in mind of the difference between “I don’t know what to say” and the crueller “What do you want me to say?” We are, Ignatieff suggests, caught between our desire to be comforted by others, and the necessity of consoling ourselves.

The figures in On Consolation exist at pivot points in history, when the promise of a divine afterlife was found wanting. Their works of writing, art, and music have pushed the western world towards secularism and an age when religion has yielded most of its power to foretell a better future to science and politics. But given our current governmental and climatic crises, are science and politics too gloomy to provide the consolation once afforded by religious faith?

“I don’t believe the Armageddon narrative,” he said. “Not only do I not believe it, I think it’s pernicious and disabling. It’s not uncommon to hear our species described as a virus, as a parasite, and a plague upon the earth. I like the human race. Who else is going to fix this?” It’s a note he found to be struck again and again throughout history, that the essential element of consolation is hope.

I wondered how the project has changed his outlook on humanity, and the future. He fell silent for a long moment, then said “The whole project made me much more hostile to ideology and political faith itself than I ever thought I would be. It made me much more pragmatic – let’s go with what works, and cut the talk.”

Before we parted, I asked if he had any advice for those seeking consolation today. His face bore an expression like pain, his eyebrows, still dark where his hair has lightened to grey, tilting together and one cheek pulling into a half-smile. “You have to have patience with yourself. You have to give yourself a break sometimes. You can’t think yourself out of certain holes. You can’t write yourself out of certain holes. You can’t play yourself out of certain pits. You just have to let time do its work, and you have to have faith that you’ll get through it.”