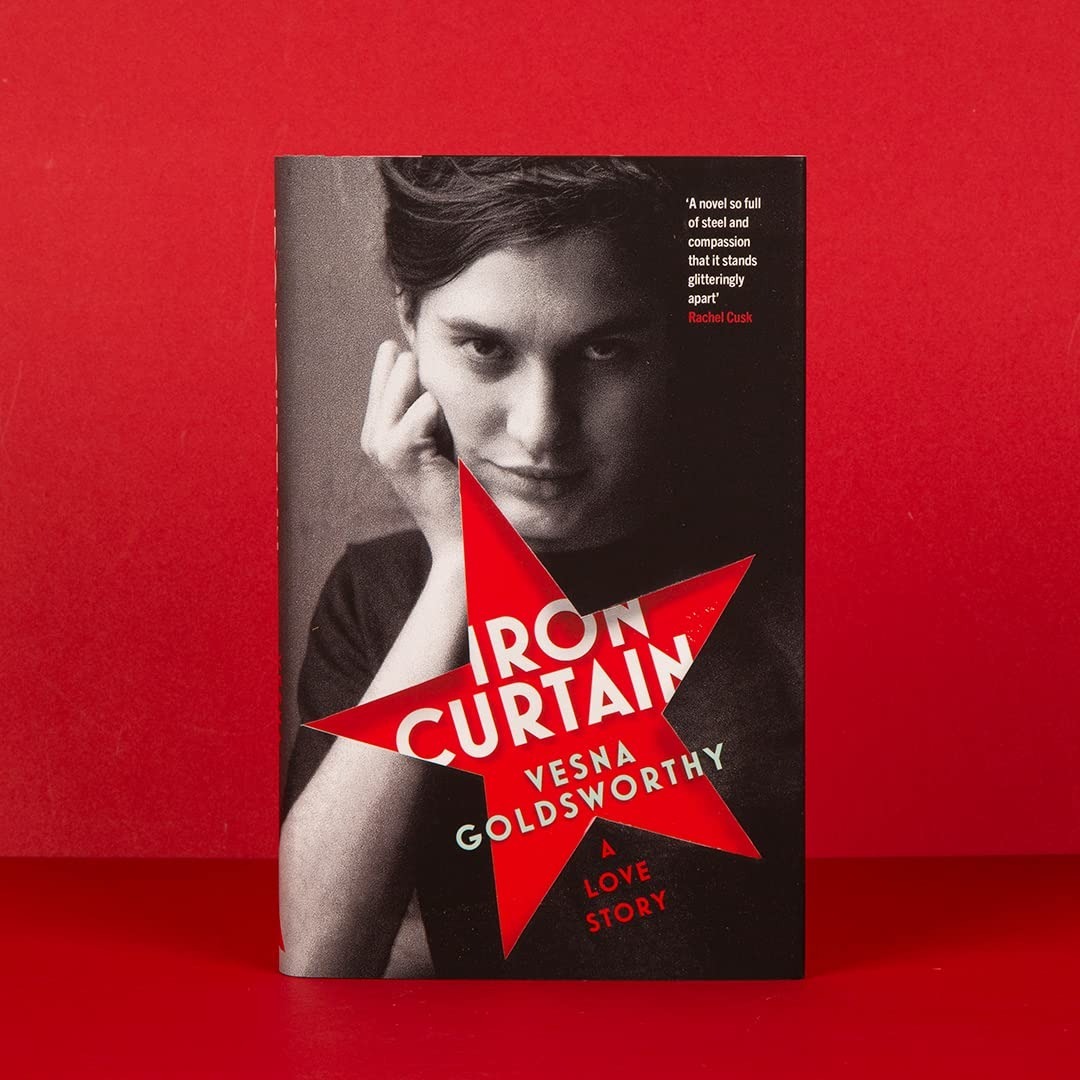

Iron Curtain: A Love Story (Chatto & Windus) by Vesna Goldsworthy

Vesna Goldsworthy’s beautifully crafted third novel begins with a quote from Euripides’ Medea: “Stronger than lover’s love is lover’s hate. Incurable in each, the wounds they make.” This is followed by a prologue marking the fall of the Berlin Wall in December 1990. Both offer clues to the novel’s denouement.

The main narrative opens nine years earlier in 1981 and is set east of the Iron Curtain. Milena Urbanska is the privileged daughter of a Francophone mother and a father who is vice-president of an unnamed satellite of the Soviet Union. She and her boyfriend Misha, an architecture student, are members of the elite, and as such there are several rules which don’t apply to them. Their families have servants (although calling them that is “studiously avoided”) and enjoy smuggled luxuries from the west. Misha drinks bitter lemon from Italy and owns “the only LP of Evita this side of the Iron Curtain.”

Neither are particularly happy. While a certain level of opulence is achievable, it never fully compensates for the lack of cultural and political freedoms. We are given a glimpse of Milena’s calculating nature early on when she admits: “I wanted a boyfriend, he was good-looking and good in bed. The local choice was limited.” However, the comforting familiarity of their relationship is abruptly curtailed when Misha dies in a senseless game of Russian roulette, a shocking act which Goldsworthy describes in spare, stark prose.

Numbed by the tragedy, Milena buries herself in her studies and later accepts a job translating scientific papers in maize research. She resigns herself to her lot. When a literary conference is held in the state capital, she agrees to interpret for Jason Connor, an English poet who proudly claims to be a Marxist. Inevitably he falls for the cool, “fierce” red princess. She in turn is attracted to Jason’s dishevelled nonchalance. “He walked through the arrivals gate in a yellow T-shirt and a pair of faded jeans, with a tatty little canvas back-pack on his shoulder.” At the end of their few, mostly “chaperoned” days together, Jason begs Milena to leave with him. She refuses at first – but months later she defects to London, where she discovers that the grass is not always greener.

The novel is neatly divided into two parts: east and west. It’s a polarity that Goldsworthy knows well, having come to the UK from Belgrade in 1986, when she was 24, to live with her British husband. A poet herself, she started writing in English, her third language, and has previously described the difficulties of straddling two cultures. She has dedicated her latest novel to “my friends who, like me, grew up east of that line from Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic”.

In the second half of Iron Curtain, she deftly illustrates western hypocrisy and the rituals of wealth that are often baffling to an outsider. Milena arrives in December 1984. Her life with Jason is not what she had expected. Funded by a grant, he’s studying for a PhD, writing and publishing his poetry, and renting student accommodation. They eventually move to a tiny one-bed flat in Shepherd’s Bush. Milena’s parents employ an agent to keep an eye on her and, on receiving reports of their daughter’s poverty, send her money.

Goldsworthy exhibits a keen eye for detail in her droll portrayal of Jason’s well-to-do family. They inhabit a draughty farmhouse with no central heating, and put the dogs’ needs before those of their fellow human beings. Milena drily observes: “The wine was some of the best I’d ever tasted, but the food was disgusting.”

Goldsworthy’s evocative descriptions of both worlds – the rigid ice of the east and the damp monotony of the west – lend a filmic quality to this layered novel. Rather than suggesting that love can conquer all divides, the couple’s story ends with a twist. The book’s prologue suggests one outcome Milena could not have predicted.

This piece is from the New Humanist summer 2022 edition. Subscribe here.