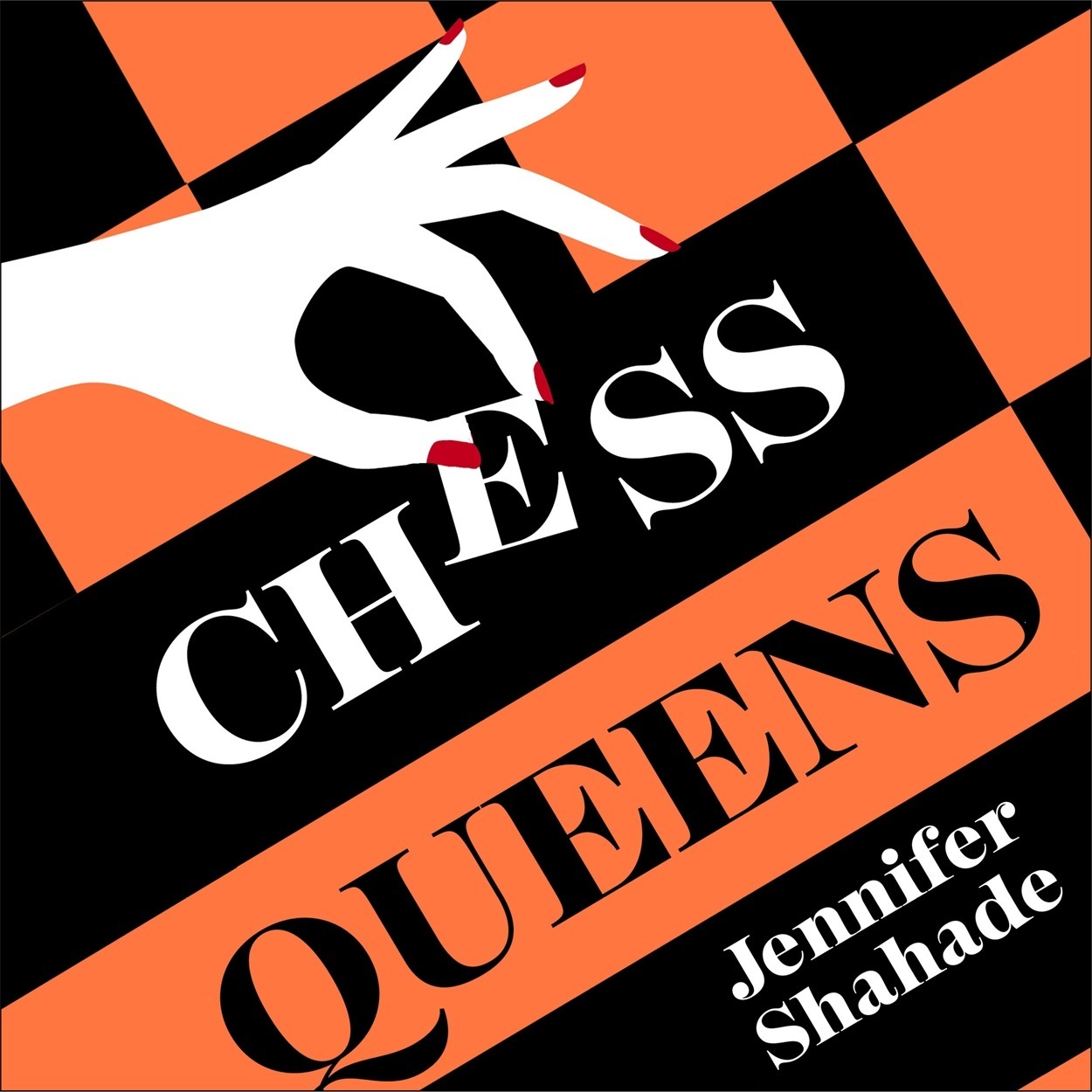

Chess Queens (Hodder & Stoughton) by Jennifer Shahade

There is no immediately apparent reason why female chess players should not compete at the same level as males: the game makes no obviously preventive physical demands. Yet there are still separate tournaments, and a separate world championship, for women. Even more strangely, the record appears to demonstrate solid reasons for this. In the upper stratospheres of chess especially, the numbers are almost as lopsided as in sprinting or weight-lifting.

Of the nearly 2,000 chess players recognised as Grandmasters by the International Chess Federation (usually referred to by its French acronym FIDE), just 39 have been women. Only one woman has ever ranked in FIDE’s top ten chess players – Judit Polgar, one of a trio of Hungarian sisters raised pretty much from birth to be chess superstars. The current reigning women’s champion, Ju Wenjun, is ranked 359th.

Chess Queens asks why this is, and how things might change. It is an expanded and updated version of a book which first appeared in 2005 under the more confrontational title Chess Bitch, which positioned the author as an exciting new face of women’s chess. Shahade, who was then in her mid-20s, had already twice won the US Women’s Chess Championship. She appeared on her book’s cover sporting violently pink hair and looking like she was just back from rehearsing with Sleater-Kinney.

Chess Queens is an understandable attempt to catch a more recent wave of interest in women and chess, coming off the back of the Netflix drama The Queen’s Gambit, in which Anya Taylor-Joy played a picturesquely tormented prodigy who used the chessboard to pave the way from a 1950s Kentucky orphanage to fame, fortune and further gripping misery. Shahade declares herself a fan of the show at the outset. “The chess,” she writes, “was more accurate than anything I’ve seen on screen, from the intensity of a chess staredown to the globetrotting glamour of a top grandmaster on tour.”

However, she is alert to the fact that the implied novelty of a female chess champion is itself an indicator of the problem. As she notes, The Queen’s Gambit screwed up on this front: the lead character refers to the (real) Georgian player Nona Gaprindashvili, the first woman to reach Grandmaster level, and makes the dismissive remark “she has never faced men”. A lawsuit is pending from Gaprindashvili, who did face – and beat – many.

Chess Queens, which is subtitled “The True Story Of A Chess Champion And The Greatest Female Players Of All Time”, is both an autobiography and a series of potted biographies. Shahade tells her own story alongside those of great female chess players she has known or played against. There is – to the relief of those, like this reviewer, who find chess fascinating without being any good at it – little technical analysis or jargon. She writes for the general reader, and does so in a dry, droll and conversational style, with a sharp eye for character quirks. Long hours spent gazing at opponents across a table may help with this: more recently, Shahade has become a successful poker player.

The book also wryly dissects the myths and suppositions long advanced in support of the idea that women are inherently inferior chess players. Shahade proposes at one point a mixed tournament held beneath a nursery full of screaming babies, to see who is really easily distracted.

As she picks these off, however, she is careful to acknowledge that women’s chess is no less varied than the women who play it: there are, for example, those who think women-only tournaments and women’s rankings are important, those that don’t, and those who have changed their minds in both directions (Shahade herself is ranked a Woman Grandmaster). There are those who have been uncomfortable with whatever attention their looks have earned them, and those who’ve been quite happy to capitalise on it.

It is an outstanding chess player’s gift, to be able to perceive a situation from a number and variety of angles incomprehensible to most of us.

This piece is from the New Humanist summer 2022 edition. Subscribe here.