Before I begin let me first apologise to Stanley Middleton. It's been a bad week. Being canned by one's publisher troubles the mind. 'Dropped', I think the industry deigns it, but that reeks too much of casualness or clumsiness. Perhaps 'pulped' is a better term: beyond the obvious associations, pulped is how your brain feels when you've been dropped. I must compare notes with Stanley, a man who, having just published his 42nd book, must have had many such trying moments during his lengthy career. 42 novels, but hardly a household name, despite being a joint-winner of the Booker. Like many senior writers he gets respectable mentions in the literary pages: a subtle writer, we're led to understand, often praised for being concerned with what goes on 'beneath the surface of lives'.

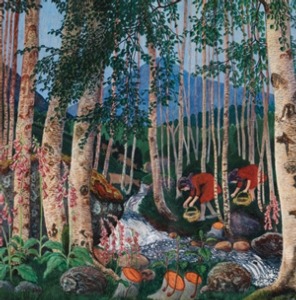

The hero, if that's not too strong a term for his latest gentle tale, is Francis Montgomery. He's a painter. In fact he's a very good painter by all accounts, perhaps even a genius. We know this because everybody in the book (wife, sister-in-law, father, principal of the college at which he works, a duchess whom he paints, even the Sunday Times) describes him as such. Some even go so far as to compare him to Rembrandt. Frank, of course, shrugs off the praise, although he spends much of the book preening himself in the glow of such adulation. We first encounter him on a long painting weekend. He's staying at a hotel in Llanfachreth, and it's all very civilised.

The hotelier even spots a quote from Gray's Elegy Frank throws at him before he sets off on his pre-breakfast amble. It's immediately evident that there's a McEwanish precision, or prissiness about Stanley's prose. Having walked for a while, Frank 'glanced at his watch and decided to turn about for the hotel'. At one point the writer accuses a character of using archaic language, but thinks nothing of giving Frank's sister-in-law lines such as 'had they matrimony in their sights?'

Frank's wife, a solicitor, is not accompanying him on the weekend. She must, you suspect, be kicking herself for missing out on it when he telephones her and reports: 'I've spent the last half an hour doing a hedge.' Next day a girl turns up and watches him work. 'She was thin, with dusty fair hair, a dress of faded yellow, sandals and no stockings.' Fiona Heatherington is 19 (which perhaps accounts for her lack of stockings), she's off to study art at Cardiff and they argue over the aesthetics of his work. Always eager to talk about himself, Frank asks her to explain his work to him but is finally trumped when she announces: 'Works of art consist of successfully surmounting self-imposed obstacles.' 'He did not wish to argue further.' Shame.

He sketches Fiona. She kisses him. ''This is the only way I can reward you,' she said, gasping.'

When Frank gets back home after his weekend, Stanley doesn't expend much effort on describing his wife, Gillian. When she and her sister turn up, we learn they are both 'slim, tall, elegant and alike in hair colour.' Rosemary, the sister-in-law, was more 'serious of face', her expression, 'pleasant'.

'Pleasant' is as good a word as any to describe the world the Montgomerys inhabit. Here are a couple of decent people in their late 40s; childless, bolstering each others self-importance, living in a cottage, with good jobs, surrounded by cheery shopkeepers and neighbours who raise their hats to strangers. The only shadow cast over their lives is the decline of Gillian's mother and Frank's father. There's of course nothing wrong with a writer portraying decent people trying to live decent lives. In many ways it's refreshing to find ordinariness portrayed fairly vividly: not an expletive in sight, nobody injecting crack cocaine into their eyeballs, no medieval codes to unravel. Frank is in his late 40s, but he's a good distance from the Parsons/Hornby misty-eyed middle-ager, burping the baby and droning on about his feelings, the Sex Pistols and how dog dirt used to be white.

The problem with this book, however, is Frank. He simply doesn't feel fortysomething. His reference points (pace the stockings), vocabulary and responses suggest a much older character. I assume (even looking vainly under the surface for deeper meanings) we're meant to find him fascinating and lovable. But he's not. He's a bore. He's also a groper. Having snogged small-breasted Fiona Heatherington, he manages a surreptitious feel of his sister-in-law's breasts when he helps her up after a tumble (one of the few moments of action in the novel). This is just good old Frank being Frank. The only character less appealing is his 90-year old father who, when not banging on about his own career or childhood to 'the ladies' is goading his son into giving up his work at the art college to take up painting full time.

The response to character is, of course, largely subjective. And it's not always necessary to like a novel's characters. If this is Stanley's intention then I underestimate him and he's pulled off quite a feat. But one senses that the writer himself is beginning to ask questions of himself. One of his recurring themes is how artists fall out of favour as they age. Frank, looking towards the future, suggests, 'the very things that I am most praised for now will bear the brunt of their attack.'

It's heartening, however, that in this age of marketing-driven publishing, a writer of 42 novels can still enjoy the support of a good publishing house. Philip Roth had a lean decade before finding the magnificent form he's on now. We look to our senior writers for wisdom, not pyrotechnics. Stanley Middleton is undoubtedly wise; perhaps the best is still to come.