"If a tenth part of the pains taken in finding signs of an all powerful benevolent god had been employed in collecting evidence to blacken the creator's character, what scope would not have been found in the animal kingdom?" declared John Stuart Mill. "It is divided into devourers and devoured, most creatures being lavishly fitted with instruments to torment their prey." He meant that to base moral values on what happens in nature would be to justify the worst excesses of human behaviour. So any god, whose will and character is revealed through nature, has a good deal to answer for. As can be seen, this most radical and courageous of thinkers had a pretty dim view of some basic traditional religious teachings.

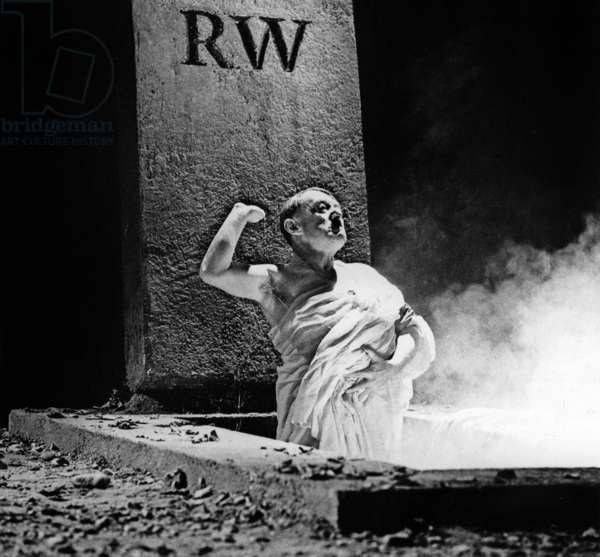

John Stuart Mill was born 200 years ago. Towards the end of his life, he took an interest in the emerging theory of evolution, but his final view tended to be that it was slightly more likely than not that there was a finite intelligent designer that had ordered the world. Given the development of evolutionary theory in recent years, it is likely that the balance of probability in his eyes would now tip away from such a designer. This kind of thinking is Mill's hallmark. He considers the evidence, reasons towards plausible explanations, and is prepared to speak out against entrenched opinions.

Mill's concern for reason and evidence arose from his extraordinary education. His father James was himself a university graduate, and later would become a leading member of the council of the 'godless' University College London, though he thought formal schooling over-rated. He embarked on an ambitious education programme for John, starting him on ancient Greek at the age of three.

This early training certainly had an impact on the young Mill and in his maturity, he believed education vital, allowing people to make better choices about themselves and about the greater good. That 'greater good' is the foundation of utilitarianism; the philosophy which advocates actions that promote the greatest happiness of the greatest number.

Some humanists have traditionally been wary of utilitarianism, precisely because of its seemingly numerical, materialist and calculating approach to social philosophy. But Mill's utilitarianism should not offend humanists, for his idea of happiness was far more enriched, involving individual flourishing that would typically involve concern for others, for feeling, for dignity and much more. Mill categorises some pleasures as more valuable than others. They are the higher pleasures. Poetry gives a higher quality pleasure than pushpin (a child's game); it is better, as he famously put it, to be a dissatisfied Socrates than a satisfied pig.

Talk of higher pleasure might make Mill sound like an elitist. In a sense, he was but the way in which he was not was that he thought that virtually everyone could achieve these higher pleasures, given better education and welfare. Advocating votes for all adults, men and women alike though still with some qualifications concerning paying taxes he consistently campaigned for women's suffrage. Indeed, his feminism is probably one of his most radical and forward-thinking principles.

It seems, indeed, that in his youth he was arrested and brought before magistrates for distributing birth control tracts. And when in 1865 he was elected to parliament as a liberal, he strongly supported one of Gladstone's most significant reforms: the Married Women's Property Act.

But despite his engagement with politics, Mill was vocal about the need for minimal state interference. The state should only be able to restrict the actions of sane adults if those actions are likely to be harmful to others, and should certainly have no business legislating on what people do privately. When he finally married his long-term love, Harriet Taylor, Mill voluntarily resigned his statutory rights, opting for a more equal partnership and refusing to allow state control of his private relationship.

However, he strongly believed that when people voluntarily take on obligations, they should honour them: so it's perfectly all right for an individual to live in an intoxicated haze, but not if that would harm children or other dependants. Having offspring creates an obligation to nurture and educate them well. If would-be parents cannot afford this, they ought to remain childless.

I suspect he would oppose maternity and paternity pay, on the grounds that we should make our own destinies and be responsible for our own choices. In that sense, he's something of a pivotal figure, hovering between the self-reliance espoused by Enlightenment figures like Adam Smith, and socialism's emphasis on the responsibilities of the state.

Perhaps Mill's most humanist principle is his commitment to liberty. To fulfil our potential, he argued, we must be free to make our own choices otherwise, we are robots. The most fundamental liberty, for Mill, is the right to free speech, which he saw as essential for progress. If what is spoken is true, that benefits us; if false, that should stimulate us to challenge. In a sentiment with powerful contemporary resonances, he maintained that mere offence that may be caused by what is spoken is swamped by the benefits of the speaking.

Mill spoke of the 'Religion of humanity', optimistic that social co-operation and fellow feeling would increase with improved conditions and education all part of the truly human flourishing life.

Peter Cave is Chairman of the Humanist Philosophers' Group