A beautiful young animated Iranian woman is standing centre stage facing a noisy comedy club audience. “Never take cocaine,” she advises sternly. “I took it once at a party. Went around all night talking really loudly about myself. Had no effect upon me at all.” Laughs and whoops of delight echo round the auditorium.

A beautiful young animated Iranian woman is standing centre stage facing a noisy comedy club audience. “Never take cocaine,” she advises sternly. “I took it once at a party. Went around all night talking really loudly about myself. Had no effect upon me at all.” Laughs and whoops of delight echo round the auditorium.

I’m watching Shappi Khorsandi on YouTube. I need to watch her closely, get her measure, because we’re due to meet tomorrow morning to discuss the next step in my career: my first appearance as a stand-up comic.

She smiles and runs into her next gag. “My Iranian mother,” she says, breaking into a staccato maternal accent, “didn’t understand Christmas. ‘Old man breaks into the house. Creeps into your bedroom. Empties his sack. You are not having Christmas.’”

Shappi is disarmingly funny, well worth the Guardian’s description of her as “Britain’s best young female comedian by any yardstick”. And that’s really just as well. In normal circumstances my animosity towards most stand-up comics – the merest glimpse of someone standing up behind a microphone on an empty stage is quite enough to have me scrambling for the television zapper – would mean that I’d be about as ready to join their company as volunteer for an Opus Dei task force.

There is one other consolation which I recite to myself as I arrive the next day at Broadcasting House for my first private lesson with Shappi. It is all being done for charity. All part of a Comic Relief lark in which four Radio Four presenters – myself, Libby Purves, Evan Davis and Peter White – spend a couple of weeks being instructed in the art of stand-up by four professional comedians before being let loose on a real night club audience in London’s East End.

I’ve been told to prepare a little act so that Shappi can make a preliminary assessment of my ability. In fact, I’m not as nervous as I should be about this first performance. For years I’ve been giving public lectures and after-dinner speeches at higher education conferences and feel confident that my repertoire of stories about eccentric academics and the daft goings-on in university committees will at least show her that I’m far from being an amateur at this business of making people laugh.

So as soon as we’re nicely settled – Shappi has brought along a bottle of Chianti to help break the ice – I get to my feet and embark upon this hilarious story about an absent-minded professor who had spent a lifetime studying short-term memory but couldn’t even remember his own name.

About halfway through I notice that something has happened to Shappi’s almost permanent smile. Her face is still set in the smiling position but it now lacks any animation. It has become a mask.

My problem, as she gently explains afterwards, with the look of someone who’s just been entrusted a sow’s ear, is that my stories are – how can she put it – a little on the long side of things. Although, of course, my tales might go down extraordinarily well with a bunch of elderly academics who didn’t get out too much, they’re not likely to have quite the same impact on a drunken bunch of East Enders who have come to regard a night out at a comedy club as the contemporary equivalent of a bit of slave-baiting at the Coliseum.

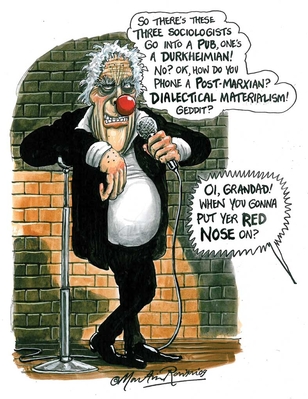

“Do you know any one-liners?” she asks hopefully. I stare back at her. Is she really asking a fully-grown sociologist if he is capable of expressing a thought, even a half thought, even an idea for an idea, in anything so compressed as a single line? Doesn’t she know that one of my bitter rivals in the factional world of the sociology of deviance once defined “to taylor” as a verb which described someone’s capacity to “weave extraordinarily elaborate patterns out of a single thread of material”? Doesn’t she recognise that succinctness for me is about as natural as a minuet to Wagner?

I can only be glad that this column has gone to press before the final showdown. For although it’s true that I have now whittled my act down to the requisite five minutes, I feel totally lost without my words. Like Proust without his adjectives. Henry James without his sentences.

Shappi likes to tell her audiences about how the audience reacted to her in Britain when she first started her stand-up act. “Hang on,” they’d go. “Wait a minute. There’s a woman on the stage.” She drops her voice. “Yes, I know. Isn’t it amazing? Some of us can now get on the stage without a pole.”

Next week there’ll be an even stranger phenomenon standing in the middle of the stage at the Comedy Café. A sociologist without a verbal overcoat. Thank you. You’ve been a lovely audience.