It was around 7pm. A regular house on a regular street in Los Pocitos, an outlying suburb of Havana. There was a short lull in the proceedings. The ceremony had been going for a couple of hours now and everyone crammed into the small space was starting to feel the heat. Some of the better prepared elegant young women snapped open fans while the men sought relief with a slug of rum. Several people milled around outside talking and drinking. A bunch of children fought for space to look through the shutterless window to see better what was happening inside. Maestro Bolaños, universally recognised as one of the most knowledgeable drummers in Cuba, nodded approval as I took my turn.

Everyone looked at me as I sat to play the lead drum. I could feel their wary concern: does he know what he’s doing? The singer began a chant for wise Obatala and I began to play the appropriate rhythm. At that moment, a young man who had earlier been sporting some stylish trainers and a natty pair of shades but was now dressed in ritual garments and brandishing a cutlass, possessed by the spirit of Ogun, the fierce warrior and blacksmith, strode briskly into the centre and demanded we play for Ochossi, the hunter, Ogun’s mythical brother. The singer looked over at me, unsure if I would be up to playing the lesser-known rhythms for the hunter god. He began to sing and I played confidently, enjoying the smiles of surprise and encouragement from the crowd dancing in front of me. It was hot, getting hotter. Every now and then merciful wafts of cool air blew in from outside as the chorus sang out strong, swaying and moving to the music. I worked up a sweat as Ogun danced, his pleasure evident when he pressed banknotes to my wet forehead and ostentatiously showered money on the other drummers. After a time the ceremony drew to a close. We walked back to Bola’s house carrying his sacred drums and placed them carefully back in the shrine room. He walked over and embraced me, kissed my cheek and said, “You played great, really strong. Oh! Everyone’s crazy for you!” Blessings from the King, nothing sweeter.

I am a percussionist – playing everything from jazz to grime – and now also a music scholar researching a PhD in ethnomusicology. Almost 20 years ago I discovered Afrocuban batá drums: centuries-old sacred instruments widely acknowledged as the most complex and demanding of all Afro-Diaspora drumming traditions. Initially falling under their musical spell, I ended up following this calling far deeper than I ever anticipated: I am now an initiated drummer with the honorific title omo Aña, which means “child of Aña” (the spirit of the drum). This prestigious appellation – earned through ritual initiation – entitles me to play consecrated batá drums in spirit possession ceremonies called tambor.

Batá drumming originally appeared in the ancient Yoruba city-state of Oyo (now part of modern Nigeria) around the 14th century. Knowledge of the tradition was taken across the Atlantic during the slave era along with the variety of spiritual practices that are known collectively as Yoruba Traditional Religion; these were reconstructed in Cuba as Regla Ocha (also known as Santería). This Afro-Diaspora religious expression involves devotion to deities called Orishas, spiritual beings that are petitioned for health, wealth, long life, children and practical help in daily life. Communication with Orishas is achieved through divination, music ceremonies, drumming, song and dance, spirit possession, prayer, and offerings of ritual foods, flowers, liquor and animal sacrifice.

Regla Ocha is one of several African traditional practices that survived the horrors of the Middle Passage and plantation slavery to be reordered to fit conditions in the New World. Others include Palo, a religious practice of BaKongo origins with a much darker, bloodier reputation than Regla Ocha, and Abakua, a male-only secret fraternity that has spiritual characteristics as well as being something of a mutual aid society. Though ancient these traditions are very much a part of modern Cuban life. It’s quite normal to see newly-initiated Santero priests (identifiable by their all-white garments) going about their daily business in central Havana. The large market at Cuatro Caminos is well stocked with ritual items like icons and altar pieces, and birds are readily available should sacrifice be required.

I once went with a priestess friend to visit her brother in hospital. He had been rushed into emergency with a sudden and serious liver problem due to his partying lifestyle. Accompanying us was her husband, a Palo priest. We went via Cuatro Caminos so he could pick up a live chicken, which he concealed in a large brown paper bag. Arriving at the hospital the wiry man pulled his dark ’60s shades down low and, looking for all the world like a sinister Caribbean Cold War hitman, surreptitiously slipped past hospital reception with the bird under his arm and went upstairs to the wards to administer a healing ceremony to his ailing, drip-fed brother-in-law. The cloak-and-dagger act proved unnecessary – none of the medical staff batted an eyelid, despite the occasional squawk from the bag. Once upstairs we said hello to Lázaro and wished the sick man well. With great effort, he pulled himself off his bed and stood holding up his drip in one hand as the Palero supported him with the other. The two men shuffled out of sight into a side room and we left them to it. That was the last I saw of that chicken. I did see Lázaro up and about a few days later at his sister’s place, smiling and laughing and promising her to take it easy on the rum in future.

These reconstituted African religious traditions have become a part of Cuba’s official national heritage. Though the communist regime is ostensibly atheist, its attitude to Regla Ocha, Palo and Abakua has a complex history, ranging from oppression and denigration to tolerance and even sometimes outright promotion. In 1962 the Conjunto Folklorico Nacional de Cuba was formed specifically to showcase, albeit in somewhat sanitised form, Afrocuban sacred music and dance. When Jean Paul Sartre saw them perform in Havana in the 1960s he compared the centrality of Orishas in the psyche of Cubans with that of the Greek Gods in the archetypal imagination of Europe.

A batá ensemble consists of three drummers whose function is to summon Orishas to “mount” their devotees in tambors. Rhythms for fearsome, “hot” Orisha like the goddess of the tempest, Oya, or her consort, the thunder god Shango, can be fast, furious and dynamic. Rhythms played for more “cool” Orisha like Yemaya, goddess of the sea, or Obatala, the Zeus-like father of the Orishas, tend to be stately and sedate. Furious, often rum-fuelled, debates rage over the correct, most authentic ways to play this music. Ritual authority is vigorously accumulated and defended by drummers, whose reputations are crucial to their livelihood as sacred performers-for-hire. A healthy dose of machismo often serves to exacerbate these disputes – only men are permitted to play consecrated batá. And only a handful of men are recognised as being ritual and musical masters whose authority is beyond question. My maestro, Bolaños, is one of these.

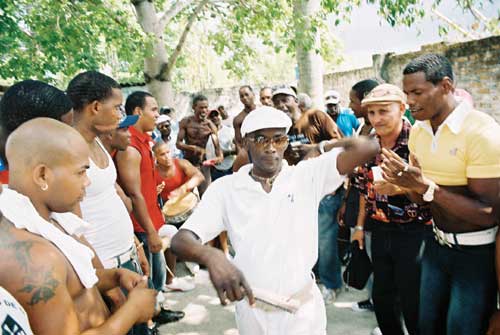

Invited by Bolaños, I went to his Abakua compound for a relaxed rumba (drum party). We all shared soup from a big cauldron set on a small fire, pulled out the drums and played and sang all afternoon. It wasn’t long before people stopped singing popular rumba songs and switched instead to ritual Abakua music. A circle formed and the men danced before each other, using the slow, deliberate gestures unique to Abakua. Watching generations of men – from seven to 70 – cook, eat, sing and dance together was deeply moving; it is easy to see why Abakua arouses such pride and passion in the male Cuban heart.

Although the elders are the custodians of ritual knowledge and defenders of correct musical style, most working ritual drummers in Havana today are young men. Like young men worldwide their interests include looking good, having fun and meeting girls. At tambors stylish guys in Diesel jeans alternate between chatting up beautiful young priestesses, sending texts on their camera phones, and communing with ancient deities through jaw-dropping displays of thunderous drumming.

One afternoon there was a tremendous thunderstorm, the kind you only get in the tropics, huge fat raindrops that crash down with great force and wash away almost anything that isn’t nailed down. Cusito, a young master singer, had told me about a tambor near the Malecon, the main coast road that runs the length of Havana. I arrived late with Jeremie, a French batá drummer. The building, a crumbling edifice with a large, tiled entrance hall, was empty save for one young drummer with bags of attitude and a lazy eye attending to a drum. “Everyone’s at the bar on the corner waiting for the rain to stop.” We walked into the bar to see several guys from Yoruba Andabo, one of Havana’s leading folkloric groups, gathered round a table drinking beer, laughing and talking loudly, exchanging good-humoured banter with the next table: a group of stunning and fearless young women, there mainly to prey on tourists like us, carriers of hard currency.

The girls beckoned to us excitedly, “Come! Sit down!” One of them grabbed me, put her arm around me, lowered her eyes and fixed me with the full-force beam of her merciless coquetry. “Oh my god! We’re in trouble! Let’s sit with the tamboreros!” my companion said with a nervous laugh. Some of the drummers knew me and invited us over. Grateful for the rescue, we sat with them and drank beer, trying to ignore the girls playfully beseeching us to join them. The guys, unfazed by the aggressive sexuality of Havana’s jiniteras, paid more attention to comparing their spinning dollar-sign belt-buckles, the latest must-have accessory for the well-dressed young Habanero. Finally Cusito arrived, talking on the phone. He snapped his mobile shut and looked up, “¡Tremenda agua!” he said with a grin.

Billy is a babalawo, an Ifa diviner priest. Ifa, an ancient West African form of divination within Regla Ocha, involves generating binary figures called odu through the random casting of ikin (palm nuts) or the throwing of an opele (a length of chain with eight pieces of coconut shell spaced along it). There are 256 possible odu. Each of these is related to specific divinatory texts handed down through the generations via oral tradition. These texts comment (in ancient, poetic Yoruba) on the quality of time and the kinds of cosmic forces envisioned as acting on the individual at that given moment. Ifa also prescribes ebo – sacrifice – to appease certain spirits or encourage certain desired outcomes. These may be anything from foodstuffs favoured by a particular Orisha (say, palm oil or yams) to animals like roosters or goats that are slaughtered so their blood can be offered as sacrifice. The meat from sacrifice is usually eaten by the supplicant and his or her religious associates and family, although there are instances – cleansing bad energy or offerings to the dead – where the carcass is disposed of in the garbage. This was presumably the fate of Lázaro’s bird.

The Ifa system demands phenomenal commitment. The ferocious quantity of working esoteric knowledge that must be assimilated is staggering. Babalawos must learn how to generate all 256 odu and memorise several Ifa verses for each one. (This is equivalent to learning 1,000 Elizabethan sonnets by heart and understanding how to apply them meaningfully to an everyday situation.) Ifa’s survival in Cuba under the horrific conditions of plantation slavery and 50 years of Communism is nothing short of miraculous, a testament to the importance and efficacy attributed to these rituals. This importance was formally marked in 2008 when Ifa divination was incorporated into UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

At Billy’s house I attended a celebration to honour the anniversary of his initiation. As blood from the sacrifices congealed on the altar in the back room, his guests – family friends and religious colleagues – sat in the front room chatting while his 18-year-old daughter serenaded us with her gentle guitar playing and sweet voice. One particularly loud character kept us entertained telling filthy stories that had all the women in the room doubled-over, screeching with laughter. Billy smiled at me and rolled his eyes at the man’s endless stream of bad jokes. “You want another drink? Help yourself.” “What lovely people,” I thought, as I reached past the goat’s head in the fridge to grab another beer.