My dentist, who usually takes advantage of my enforced silence to tell me in tedious detail about his relentless pursuit of salmon in Scottish rivers, was being unusually philosophical. “There’s one certain sign that you’re getting old,” he told me as he bore down on a disintegrating molar with his high-speed drill. “You know what it is?” He mistakenly took my anguished gurgle as a sign of interest. “The one certain sign is that when things start to go wrong with you it’s an even bet that they’re not going to get any better.Twist your ankle when you’re thirty and it heals in weeks. Twist your ankle when you’re seventy and you’re stuck with a weak ankle for the rest of your natural.”

My dentist, who usually takes advantage of my enforced silence to tell me in tedious detail about his relentless pursuit of salmon in Scottish rivers, was being unusually philosophical. “There’s one certain sign that you’re getting old,” he told me as he bore down on a disintegrating molar with his high-speed drill. “You know what it is?” He mistakenly took my anguished gurgle as a sign of interest. “The one certain sign is that when things start to go wrong with you it’s an even bet that they’re not going to get any better.Twist your ankle when you’re thirty and it heals in weeks. Twist your ankle when you’re seventy and you’re stuck with a weak ankle for the rest of your natural.”

If my mouth had been my own I might have told him that the very last thing I wanted to learn from any of my lengthening list of health specialists was yet another sign of ageing. And if there’d been enough time between rinses I’d certainly have wanted to add that my decision to resign from my local gym was a direct result of being told by an instructor that my wish for a firmer stomach was well beyond the reach of his master’s degree in Sport Science. He’d gone on to explain that my stomach had been inflated so often in my long life that it now lacked all tensility. “A bit like a leftover Christmas balloon,” he’d added helpfully, turning up the pace of the treadmill so suddenly that for a second I feared I might take off altogether and end up hovering above the gym with my legs still racing away like a cartoon cat.

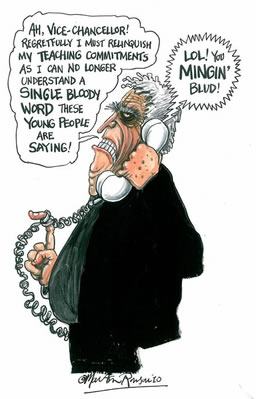

It is not, however, the inevitable increase in physical impediments that most concerns me. What is far more troubling is my growing mental inability to know what might be of interest or concern to people younger than myself. This first became a problem when I was teaching a university course in Popular Culture and realised that my constant references to the distinctive merits of the Beatles or the Rolling Stones had about as much cultural relevance to the rows of silent faces before me as a critical appreciation of the middle years of Marie Lloyd. In desperation I once asked the seminar group to tell me which groups were currently “big on the scene”. Nobody spoke for a moment. But then when I persisted, a young woman in the second row with quite enough jewellery stitched into her face to deck a Hatton Garden window gently asked me what exactly I meant by “the scene”.

Nowadays the problem has grown. I not only don’t know the cultural preoccupations of teenagers but I simply have no idea what might be of cultural interest to anyone who is not my age. Should I mention Leonard Cohen to 40-year-olds? Try out Beyonce on my son? Check out how the editorial staff of the New Humanist feel about Bruce Springsteen? See how my radio producer responds to the idea of using John Coltrane in a musical link?

Of even more concern is my alarming loss of any sense of chronology. Try as I might, I can no longer remember how popular culture fits together. Was Marilyn Monroe around at the same time as Anita Ekberg or even Anita Pallenberg? Were James Stewart and Jerry Lewis contemporaries? Did I see The Third Man before or after Gone With The Wind? Did Glam Rock precede or follow Punk? And neither can I remember who is dead and who has simply left what I still like to call “the scene”. I’m fine on John Lennon and Otis Redding and the Big Bopper but how about Frank Zappa, Donovan and Captain Beefheart? I have a pretty good idea that Peter, Paul and Mary are no more. But is that because they’ve lost Mary? Or Peter? Or Paul?

None of this would matter so much if I could turn to anecdotes and jokes as a way of entertaining my guests. But I’ve noticed recently that I’m beginning to follow in my father’s footsteps and repeat the same stories over and over again. Sometimes in the same evening. And to the same people. Only last week I leaned over the dinner table and asked Rosemary and Stephen if they’d heard the one about the man who went to the doctor’s and said he feared that he was suffering from short-term memory loss. “Really,” said the doctor. “How long have you had this problem?” And the man said, “What problem?” When nobody laughed I wondered aloud about their sense of humour. “It’s fully intact,” said Stephen reassuringly. “In fact much the same as it was twenty minutes ago when you told that joke for the first time.”