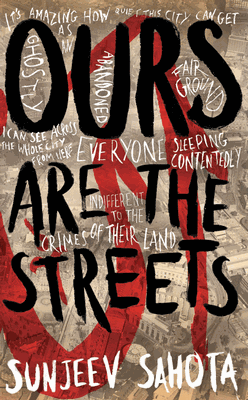

Ours Are The Streets

Ours Are The Streets

It may be a little odd to open a review – rather than close it – with a conclusion. But in the case of Ours Are the Streets, a novel by the Derbyshire youngster Sunjeev Sahota about a homegrown suicide bomber, such a break with convention is called for. Here goes: it didn’t blow me away.

OK, OK. But if you thought that pun was in poor taste, compare it with a line from the novel itself: “it were touching midnight when he got in and hung his brown bomber jacket up.” Yes, I know, two wrongs don’t make a right. But the difference is that my pun was intentional. Sunjeev Sahota’s was not. (This is no Four Lions. Sahota is always earnest.)

It is this kind of sloppy prose that marks the novel out as the virgin voyage of a young writer. Examples abound: “I spent the whole of the tram ride looking at the passengers from under my eyes” (under my eyes?); “the long feminine eyebrows [were] peaking down” (peaking down?); “he pushed his sunglasses up onto his helmet” (sunglasses don’t fit on a helmet); “blowing over the top of the steel glass to cool it” (steel glass? Steel mug, surely?). It’s like being at the mercy of a learner driver.

But the blunders on the surface of the text pale in comparison to the flaws in the underlying concept of the novel. This is, ostensibly, a suicide bomber’s confession, addressed in the first person to his baby daughter, wife and parents. How is it, then, that our chap, at the height of his religious fervour and suicidal intensity, begins by telling his loved ones about a blow job? (“I loved the feel of my weight cushioned inside her like that.”) How is it that he repeatedly recalls, without the slightest hesitation, his girlfriend’s “hard pink nipples”? OK, so occasionally he reminds us that “this is all just a form of du’a, isn’t it? a form of prayer.” And from time to time he throws in an inexplicable “Ameen”. But this is not the voice of a suicide bomber. This is the author speaking out of the side of his mouth.

It is not all bad news, however. The narrator’s depiction of his downtrodden immigrant father is remarkably vivid and well-observed: “the shame would wash down over him, over his small eyes, changing his cheery and beautiful face into a plain and disappointed one.” And the scenes set in Pakistan and Afghanistan contain passages of startling beauty and poignancy: “he used his foot to push [the boat] off into the water, and I felt my stomach dip as we were freed from the green muddy lime”.

But the warm glow fades when Sahota overlooks the obvious necessity of exploring the radicalisation process (needless to say, a glaring omission in a novel such as this). The narrator is lonely, disenfranchised, mentally unstable – fair enough. But believe it or not, he shows little interest in fundamentalist ideology. He has an identity crisis, but his relationship with Allah and Islam is nothing more than cosmetic; as a consequence, the book cannot stand up against John Updike’s Terrorist, or even Martin Amis’s patchy short story “The Last Days of Muhammad Atta”.

Funnily enough, the unusual cover design is something of a giveaway. It features a passage from the book laid out in stark, white lettering, which is pretty much the only articulation of fundamentalist ideology in the novel: “I can see across the whole city from here ... everyone sleeping contentedly, indifferent to the crimes of their land.” Surely this added emphasis wasn’t intended to compensate for the hole in the text. Was it?

Ours Are the Streets does indeed contain flashes of literary promise. If the author had set his sights lower – writing in the third person, perhaps, and focusing on the British Asian experience rather than suicide murder – the result might have been less of a curate’s egg. As it stands, however, it didn’t blow me away.

But then, I’ve mentioned that already.