The osprey burst in suddenly as if by magic.”

The osprey burst in suddenly as if by magic.”

“I’m sorry.”

“The osprey burst in suddenly as if by magic. Nine letters altogether. Two words. Three letters and six letters.”

“Give up.”

“Already?”

“Yes, I give up already.”

“It’s ‘Hey Presto’. An anagram of ‘the osprey’. ‘Suddenly as if by magic.’ Get it?”

I admitted that I got it. Not just the clue but my old friend Harry’s passionate new interest in crosswords. Ever since he’d learned from a lengthy article in Psychology Today that he could postpone the onset of dementia by regularly exercising his brain, he’s devoted his life to searching out every available form of intellectual exercise.

He began with crosswords but then widened his range to encompass KenKen, Kakuro, Codewords and, of course, Sudoku. (His wife, Doreen, once told me that he could knock off a Super Fiendish in less time than it took her to empty the dishwasher).

But word and number play was nothing more than a warm-up, a brief mental jog round the block, compared to Harry’s more advanced mental exercise regime. Whereas his reading matter had traditionally been confined to the extravagantly opinionated columns of middlebrow newspapers, he now strove to keep his mind in proper working order by sparring with philosophical heavyweights.

“Listen to this,” he said one morning when I’d merely popped round to borrow Doreen’s knife sharpener. “Listen to this. ‘It was Christianity which first painted the Devil on the world’s walls. It was Christianity which first brought sin into the world. Belief in the cure which it offered has now been shaken to its deepest roots but belief in the sickness which it taught and propagated continues to exist.’ Wonderful stuff, eh?”

And with that he slumped back in his favourite armchair, rubbed his hands together with glee and announced that the passage came from Nietzsche. “Yes, Nietzsche. You should try him. Difficult going at first. But when your brain gets up to speed you can understand nearly every word.”

Doreen quickly tired of these mental workouts. Whereas she and her husband had always, in the interests of sociability, allowed their dinner guests to parade a customary collection of prejudices without any serious challenge, these same guests now found, as they inveighed against the psychopathic behaviour of cyclists or the persistent lack of medium-sized shopping trolleys outside Waitrose, that they were required to answer for logical failures in the development of their argument. As Doreen told me one afternoon while Harry was busy downloading some logarithmic puzzles, she’d had to email an apology to her best friend Alice after Harry had twice accused her of resorting to synthetic a prioris during a conversation about the Labour Party’s stance on the winter fuel allowance.

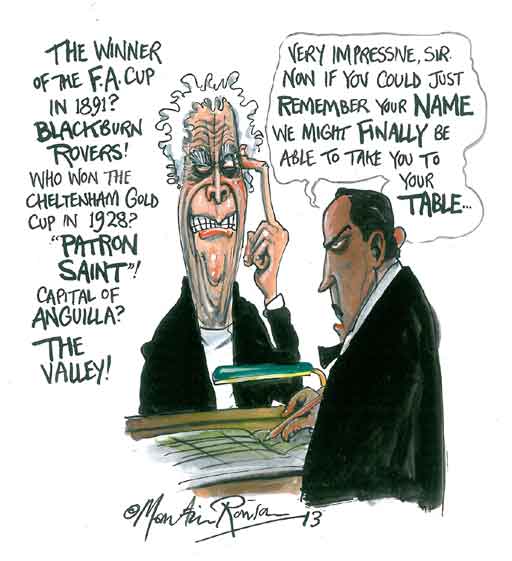

And then, to compound matters, there were the memory tests. In much the manner of the old pugilist who invites you to punch him hard in the stomach, Harry would routinely issue mental challenges. “Who was Everton’s manager when they won the League Championship?” he’d demand to know almost before you were halfway down the hall. “Harry Catterick,” he’d boom as you admitted your ignorance. “Harry bleeding Catterick.”

Even bedtime didn’t halt the regime. Doreen confided that her husband was now quite unable to sleep until he’d tested his memory by reciting poetry he’d first learned at school. Their sex life had somewhat gone off the boil after they’d both passed their 60th birthday but matters had not been helped when their last attempt at sexual congress had come to a sudden halt as Harry became increasingly frustrated at this failure to remember Christina Rossetti’s middle name. “You mean Georgina?” I offered. “That’s the one,” said Doreen.

And then just two months after that very conversation, tragedy struck. It seems that Harry had decided to test his memory of great paintings by wandering round the National Gallery and guessing the artist and the title of the picture before consulting the plaque. We have no way of knowing the success or otherwise of this new defence against dementia because of what occurred immediately afterwards.

It seems that as Harry descended the broad steps of the gallery, still clutching a copy of that morning’s Times containing, as we were to discover later, a completed cryptic crossword, he slipped and fell so heavily that he ended up in a semi-conscious state on the pavement of Trafalgar Square. So dramatic was the fall that some passers-by, fresh from examining the figure on the fourth plinth, took his near-death fall as a minor piece of conceptual art. “People began taking pictures with their mobile phones,” Doreen told me from the other side of his hospital bed.

The consultant was optimistic about Harry’s chances of making a full recovery. Indeed, he admitted to being extremely impressed by Harry’s insistence upon reciting the names of Arsenal’s 1979 cup-winning team as he was wheeled from the theatre. “Nothing at all wrong with his mind,” he smilingly told Doreen. “Such a pity he couldn’t have kept his legs in better trim.”