A Place in the Country by WG Sebald (Hamish Hamilton)

This book contains essays on five writers and one painter, all from, or with connections to, the Alemannic-speaking regions of Switzerland and southern Germany, mainly Swabia and Baden-Württemberg. All but one, possibly two, are largely unknown in the English-speaking world. None of them are at all conventional or representative of the dominant trends in the literature of their time. It covers a period of around two hundred years, beginning before the French Revolution and including times of intense strife, warfare and convulsion, though the authors may not directly write about this. It is arranged in a loosely chronological order that appears to suggest a historical narrative, though the book’s author (another Swabian) sometimes seems to be more concerned with matters of literary style and the somewhat rarefied question of prosody in certain traditions of German writing. There is a saturnine undercurrent and tone throughout. All in all, then, a typical WG Sebald performance.

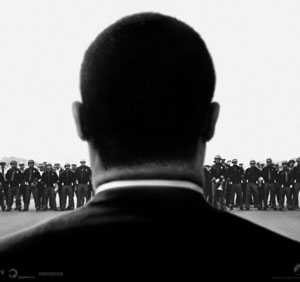

Back in the 1990s Sebald was the most engaging and seductive writer in action; a feeling only exacerbated by the difficulty of knowing exactly what it was one was reading. His books appeared to be narrated by a German of the post-war generation who had moved to Britain and lived here for many years. These facts matched what we knew of the author himself. The books went on to describe journeys that may have taken place. There were photographs that may or may not – they were always intriguingly grainy and vague – have illustrated the events discussed. Better still, there were long digressions prompted by geography and the quiddity of the places the narrator/author passed through. The digressions included, but were not confined to, philosophy, literature, famous writers, obscure writers, cosmology, the fauna of Germany, the fauna of Suffolk (there’s a lot of East Anglia in Sebald books. The flatness seems to have appealed to him, possibly for the contrary reason that the man himself was born in the German Alps). The eclectic list went on and on, but over and above all was a consideration of history, the violence and destructiveness of it, the inescapable, relentless catastrophe. James Baldwin said that people are trapped in history, and history is trapped in them. The characters in Sebald books were the victims of this process of imprisonment.

It shouldn’t be thought that there was no humour, though it was of an understated kind. Take The Rings of Saturn, for example. The narrator/author describes a long European walk and wonders whether he has become preoccupied with “the paralysing horror that had come over me at various times when confronted with the traces of destruction, reaching far back into the past, that were evident even in that remote place”. But he is nowhere near Dresden or Austerlitz or the Somme, he’s outside Norwich.

The books that made him famous and valued were the ones that appeared to be works of the imagination that were laced through with non-fiction (or appeared to be so. It could be hard to tell). But the current book is not his first work of definite and obvious non-fiction. On the Natural History of Destruction was a collection of essays that considered the terrible devastation of the Allied (in fact, mainly British) area bombing campaign of the Second World War. Yet this dramatic title could serve as an alternative to the bucolic A Place in the Country. Each of the writers it surveys registered in their work the long build-up to the ideological cataclysm of the 20th century.

Sebald-watchers will recognise the master’s unique tone in only one of these essays. On Jean-Jacques Rousseau follows the narrator – whom we assume to be Sebald himself, though we cannot be sure – to the Île Saint Pierre – on a trip we assume actually took place, though who knows? – where Rousseau once stayed. In what may have been the last time before the rise of the modern dictators when philosophy was considered important enough for its practitioners to be persecuted by the state, Rousseau went there because he was on the run. Accused of being an enemy of religion, Rousseau saw his books banned (in some places they were actually burned) and was chased out of Geneva. During years of exile, he ran to many places, one of them being this island on the Lac de Bienne. Biographies of Rousseau describe him as a near graphomaniac, a man so in thrall to writing that he produced thousands of pages of prose, verse and drama even as he fled the secret police. He suffered from a compulsion to write, perhaps driven by mental illness. Except that, according to Sebald, it seems to have left him while he was on the island. There he was content to observe nature. He dreamed of finishing with the philosophical work and devoting himself to the study of the local flora.

Eduard Friedrich Mörike (1804–75) and Gottfried Keller (1819–90) may have been writing in the shadow of the Napoleonic wars, but did not themselves experience war. They lived through political upheavals such as the revolutions of 1848, but Europe would not suffer continent-wide catastrophe again until 1914. But living in peaceful and settled times did not make them content. Instead their stories and poems turned inwards and explored psychological disquiet and anxiety. Sebald believed that the Swabian poet Mörike had “at his back the revolutionary upheavals of the end of the eighteenth century, while the terrors which [were to] herald the new age of industrialization [were] already silhouetted on the horizon.”

Sebald reserves his greatest admiration and affection for the Swiss-born Robert Walser (1878 -1956) who moved to Berlin before the First World War and wrote brief, evanescent stories of city life that have come to be seen as masterpieces of German modernism. He lived and wrote at a time when the anxieties of the 19th century were finally coming to fruition in the disasters of the two great 20th-century wars, but, characteristically for a hero of Sebald, he did not address those events directly. Walser could have served as a model for all the awkward, eccentric and haunted characters that populate Sebald’s fiction.

Spending up to 13 hours a day at his desk, he was dedicated to writing even to the point of damaging his health, though trying to live on the tiny sums of money that were all the remuneration he ever managed to earn from literature may have done for him in the end anyway. Walser suffered a nervous breakdown and was committed to an asylum in Switzerland. He died there in 1956, so outliving the Nazis who, had they been able to get their hands on him, would almost certainly have destroyed the writer with the same vigour with which they banned his books.

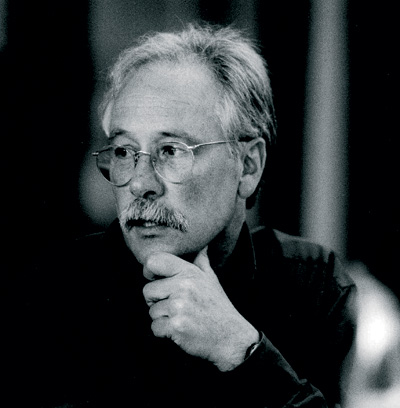

The book’s coda is an essay on the painter Jan Peter Tripp, childhood friend of the author and collaborator on some of his previous books, such as the poetry collection Unrecounted, and it is a revelation. A contemporary and friend of Sebald from school, Tripp painted carefully naturalistic but lugubrious paintings that mark him out as a brother spirit to his childhood companion. The inclusion of a graphic artist at the end of a book of writers – as if there is nothing more to be said – gives the publisher the opportunity to reproduce some of Tripp’s work. These pictures join the illustrations selected for each of the previous subjects.

A Place in the Country joins Sebald’s other books as a handsome mixture of prose and illustration. Though the main theme of the book appears to be the arc of history bending towards disaster, there is much else to be enjoyed here. Pleasure in the natural world and the peculiarities of everyday life appears again and again. A deeply humanist vision, then, if not always a comforting one.